Geyl collection

The man who kept almost everything he wrote

Vain, arrogant, brilliant, controversial, famous, notorious, sharp-witted, self-assured, shameless, innovative, hypercritical, a libertine: all of this can be said of Pieter Geyl, one of the Netherlands’ most internationally renowned historians. Convinced of his own importance, Geyl kept almost all the letters and articles he wrote and received in an extensive archive measuring over 40 linear metres. A true gold mine for researchers who want to learn more about this fascinating man, the circles he moved in, his opponents and the times he lived in.

Pieter Catharinus Arie Geijl (1887-1966), also spelled as Geyl graduated with distinction in Leiden in 1911 and obtained his doctoral degree two years later. He left for London the same year where he became a correspondent for the Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant. His reports, looks and knowledge did not go unnoticed: in 1919 a special chair in Dutch Studies was created for him at the University of London. In the meantime he supported the Flemish Movement, promoted the Greater Dutch Thinking and developed his concept for the Dutch tribe which also included Flanders and South-Africa. A stream of publications by his hand began to emerge which only stopped at his death.

Just you wait, chum for the final reckoning, then you are the first we will pick up in Utrecht to make you some 25 centimetres shorter!

Plagiarism and controversy

When Geyl was appointed professor of Modern History in Utrecht in 1936 the event met with some resistance. Geyl had already established his reputation in the Colenbrander case, an academic riot about plagiarism, and by his critical attitude towards the Dutch monarchy. He was not afraid of controversy, and he offended many people by his biting pen. As one of the first, he saw the dangers of rising fascism, which led to threats to his address. The Nazi’s did not like him, and in 1940 he was taken hostage by the Germans and interned in Buchenwald.

Translation reads roughly: Only a bastard like you could write something like this. It is a sad thing we still have bastards like you who want to sell out their country to a pirate state. A Dutchman who is pro English is nothing less than a traitor. A Dutchman who is anti-German is nothing less than bastard. But it's up to you. But don't you be afraid, prof, England's power is finished, and if you want to be a slave of that rotten people so much, why don't you go and live there. Good riddance! We Dutch at least are proud, belonging to the German tribe, as do the Anglo-Saxons which makes them Teutons as well. Or not, stupid prof, poor soul or didn't you know they came from the Elbe? Just you wait, chum for the final reckoning, then you are the first we will pick up in Utrecht to make you some 25 centimetres shorter!

After the war Geyl’s star rose to great heights: his polemic with the English historian Toynbee brought him international fame, his books were translated and were highly praised, his tours abroad attracted many visitors, and he received honorary doctorates and awards. In 1958, the year in which he was accorded emeritus status, he was awarded the P.C.Hooft Prize, a prestigious Dutch literary award. Together with Johan Huizinga, he was considered the most famous historian in the Netherlands.

One could interpret historiography as a never-ending discussion

A true gift

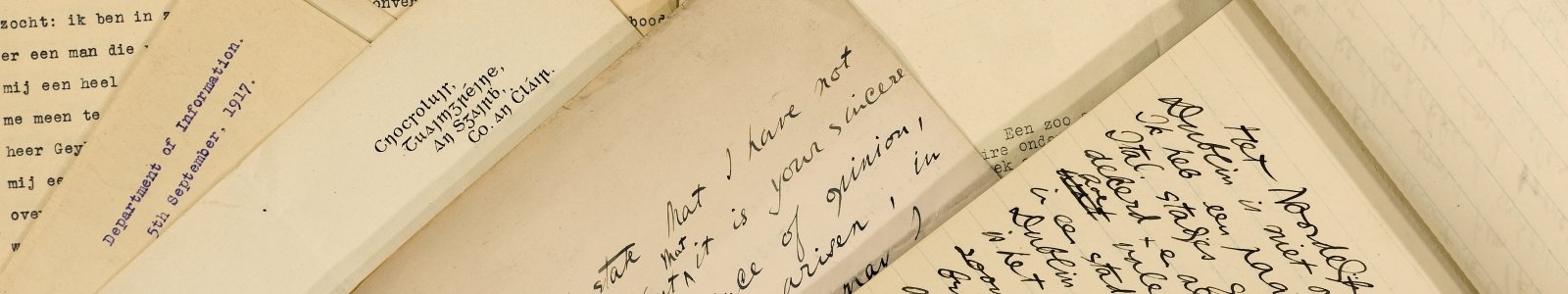

Geyl donated his extensive archive to Utrecht University Library. It is a treasury of information about Geyl himself, his family, acquaintances, colleagues, historians, opponents, administrators, politicians, writers and others, especially where the correspondence is concerned of which Geyl kept the letters and his responses. From science and politics to gossip, nothing is left undiscussed. The archive also contains his remarkable autobiography (up to 1940, published in 2009), lecture summaries, lectures, concepts for publications (in the field of history and literature), documents coming from university and other committees which he was part of and all kinds of personal details. It seldom occurs that the academic life of one person of such stature has been preserved in all its aspects and in such detail. Geyl considered this to be only right, and who are we to contradict him?