Antiphonary St. Paul's Abbey (fragments)

Microtonal intervals: a 12th-century clash of cultures

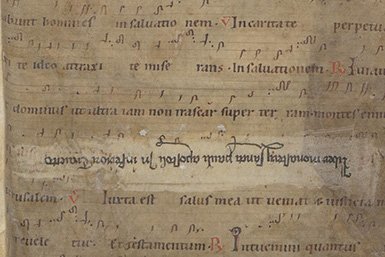

‘University Library Utrecht, Ms. fr. 4.3’ refers to a collection of twenty folios of manuscript fragments which were once part of a 12th-century antiphonary, and belonged to St Paul’s Abbey in Utrecht. Its musical notation includes symbols for microtonal intervals which point to the survival of local chant traditions despite Roman attempts at standardization.

The Transmission of Chant

Since the ninth century, signs with musical meanings were added above chant texts as a mnemonic tool for the melodies linked to the text. These symbols, called neumes, range from a dot (punctum) or a diagonal line (virga) for one note to figures representing a melodic movement linked to a syllable. Although recent research reveals that the early neumes contain other information for the performance of chant, it is not possible to define exact intervals between pitches. Hence they are called adiastematic neumes (Greek, lit. ‘without intervals); the exact pitches of the melodies still had to be learned by heart. Several regional neume families existed. Research by the Utrecht musicologist Ike de Loos indicates that the Utrecht neumes belonged to the Utrecht-Stavelot-Trier family, after the region where these neumes were current.

Revolution

Since the ninth century, signs with musical meanings were added above chant texts as a mnemonic tool for the melodies linked to the text. These symbols, called neumes, range from a dot (punctum) or a diagonal line (virga) for one note to figures representing a melodic movement linked to a syllable. Although recent research reveals that the early neumes contain other information for the performance of chant, it is not possible to define exact intervals between pitches. Hence they are called adiastematic neumes (Greek, lit. ‘without intervals); the exact pitches of the melodies still had to be learned by heart. Several regional neume families existed. Research by the Utrecht musicologist Ike de Loos indicates that the Utrecht neumes belonged to the Utrecht-Stavelot-Trier family, after the region where these neumes were current.

Gregorian chant

In order to understand some remarkable notational aspects of the Utrecht-Stavelot-Trier family (which has both early adiastematic and later diastematic representatives, amongst which the Utrecht fragments under discussion), some music theory is needed. Gregorian chant as written on the staff based upon Guido’s invention underlies a diatonic pitch system. Simplified, the diatonic system applies a scale of whole tones, with semitones between e/f and b/c. Starting at c, it is the scale on the piano with the white keys only. Guido added the letters c and/or f as clefs to the lines of his grid: the intervals leading up to the c and/or f line were the semitones. Sharps (raising a pitch by a semitone) were not applied in Guido's diatonic system. Only one flat was allowed: b could be lowered by a semitone to b-flat. The diatonic scale was known from Antique treatises. But in these treatises, other tonal systems are mentioned as well, in which steps occur that we now would call microtonal (smaller than a semitone). Nowadays, Western ears perceive these intervals as ‘strange’ or ‘false’. Listen to Arabic or Indian music for example: the ‘strange’ notes to Western ears are microtonal intervals.

Microtonal intervals: a clash of cultures

The staff travelled from Italy to northern Europe fairly fast, backed by Pope John XIX, who had quite a centralist view on the performance of liturgy, its chants included. Guido's ‘invention’ was a perfect tool for further standardizing the performance of melodies. But apparently, many local traditions applied notes that did not fit on Guido's diatonic grid, so their scribes introduced special symbols to represent these notes belonging to their tradition. It is in the diastematic Utrecht-Stavelot-Trier family where by the superimposition of the diatonic grid in combination with special neumes and other signs previous non-diatonic traditions surface. Most remarkable are the symbols that represent intervals smaller than a semitone.

Clivis and porrectus

In the Utrecht fragments three symbols occur that represent microtonal intervals: two neumes (a clivis, representing a microtonal downward step and a porrectus in which a microtonal upward step can be represented) and a special b-flat sign. The microtonal steps occur between e-f and b-c, two semitonal intervals in diatonic music. These neumes are also found in the antiphonary of St Mary’s Chapter (Utrecht, University Library, Ms. 406), mainly of the 12th century, which is the most famous manuscript of the same neume family. This manuscript can be accessed digitally via DIAMM (registration required (free)). Other neumes may represent microtonal intervals as well, but their interpretation is more complicated and subject of debate. If all these neumes indeed represent microtonal intervals, then pre-Guidonian chant was full of it.

Open questions

Many questions remain about the origin, the syntax and the function of microtonal intervals in chant. Their origin may be Frankish, or perhaps they reflect Hellenized Christian practices, introduced by the so-called Syrian Popes (7th-8th centuries). It may also be Byzantine. Other hypotheses see them originating from contacts with Arab culture during the 10th and 11th centuries. Is their underlying syntax based upon non-diatonic scales, or were they merely applied as deliberate ornamentations, like trills nowadays? An analysis of the positions of microtonal intervals in the Utrecht fragments seems to indicate that their positions might at least have had a mnemonic function: a microtonal interval as part of a marker for the content of the melody fragment following it.

The Utrecht fragments

University Library Utrecht, Ms. fr. 4.3 consists of 20 folios, but the digitized version includes also a folio discovered in the Louvain University Library (BRES Ms. 1290) with identical codicological and palaeographical characteristics, their notation included. It has been digitized by kind permission of the Louvain University Library. The 21 folios (the Utrecht fragments referred to above) belonged to an early 12th-century antiphonary from St Paul’s Abbey in Utrecht. They were or still are bound as flyleaves into 15th-century printed books from the library of St Paul’s Abbey. It has been established that the binder(s) used flyleaves from old manuscripts from the abbey itself. The order of the leaves is given here below, with reference to the ‘page number’ in the digital version. For the catalogue numbers of the 15th-century printed books (E fol 147, F qu 116, etc.), see the records in the electronic catalogue.

Author

Leo Lousberg, November 2013; adjusted March 2014