Anonymous Utrecht jotter

Sex, politics and religion in seventeenth-century Utrecht

In the years 1678–1679 a young freethinker scribbled daring remarks in an unsightly jotter. By all appearances, the author (as yet unidentified) was a student from Utrecht, well connected, though at the time politically incapacitated, leaning towards the heterodox and the phantastic, but with an eclectic mindset and quite possibly under the veil of a perfectly orthodox public demeanour.

A motley collection of libertine notes

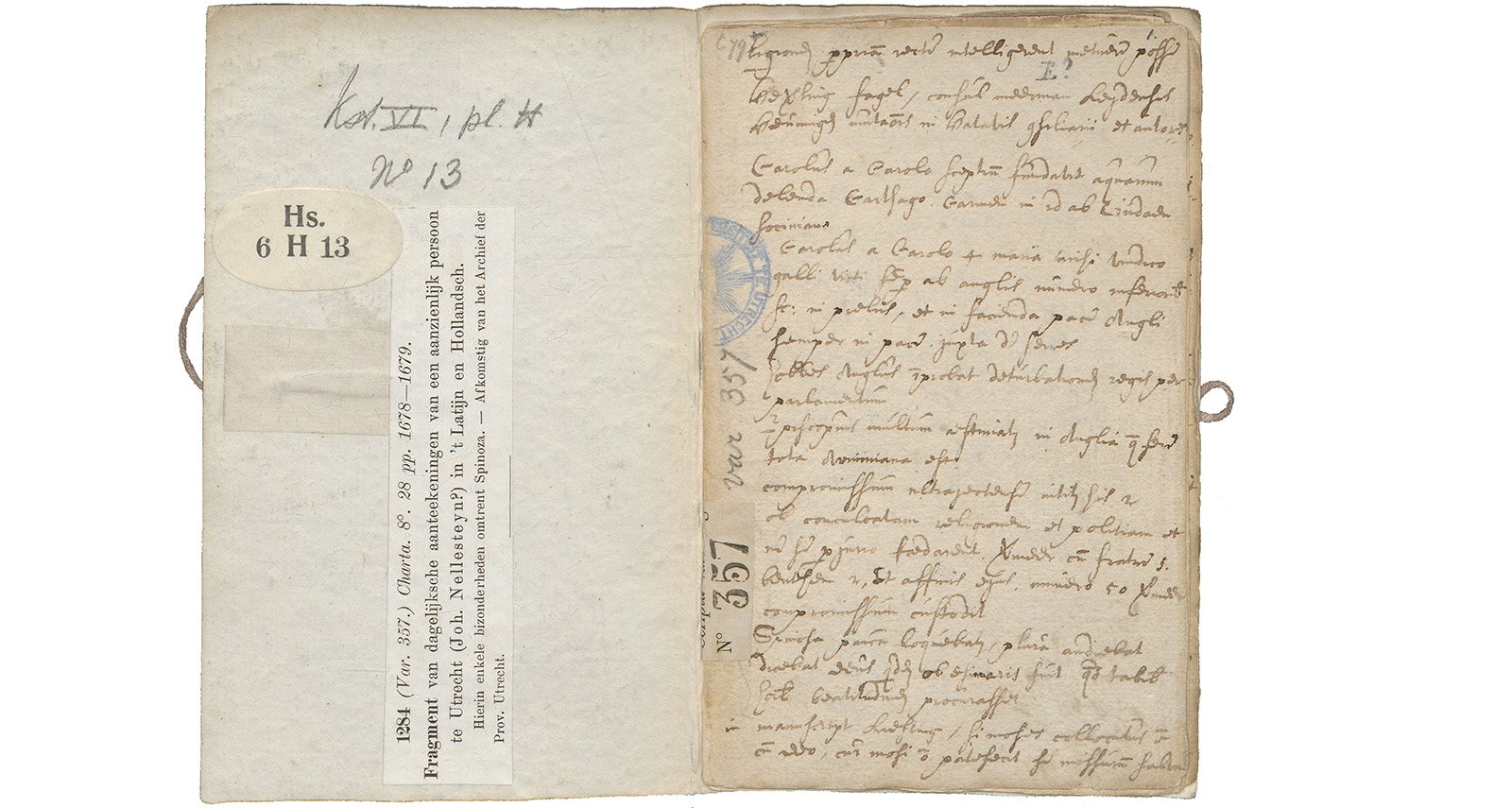

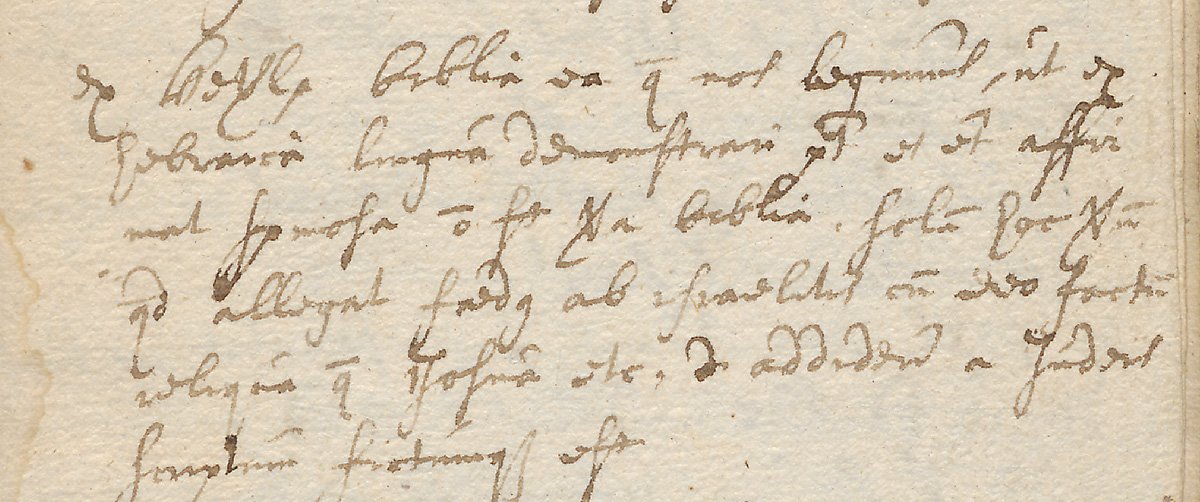

His notebook is kept in Utrecht University Library (Ms. 1284), and a critical edition of it (with an English translation) has recently been published by Piet Steenbakkers, Jetze Touber and Jeroen van de Ven. It contains some 170 entries, that were jotted down hastily, often unconnected, about a wide range of topics. Most items are in Latin, some in Dutch. The author obviously did not intend to publish the material he collected. His passionately anti-Orangist sentiments, impudent views of the Bible and sexual preoccupations would have imperiled him if his notes had become public. Rather than gathering material with an eye to publication, the function of the notebook was to serve as a repository for bits of information and apophthegms its author deemed memorable – for whatever reason. He had a fascination for all things novel, exciting or juicy: Spinoza figures prominently in the notebook, but even more so the notorious eroticist Adrianus Beverland, who must have been a friend of the author.

Uncensored

Manuscript 1284 offers a rare insight into the uncensored fascinations of a member of the Dutch elite in a period in which society and ideas underwent drastic change. These few sheets reflect the variety of subjects that occupied an adventurous and bright, albeit not brilliant mind of the late seventeenth century. It is precisely the mediocrity that transpires from the jottings, combined with the range of topics, that makes this notebook so interesting. It reads like a standard assortment of themes that would fascinate a youngster craving for intellectual thrills. The notebook provides a panoramic view of the territory covered by libertinage, seen through the eyes of a consumer, rather than a producer of ideas

Unedited

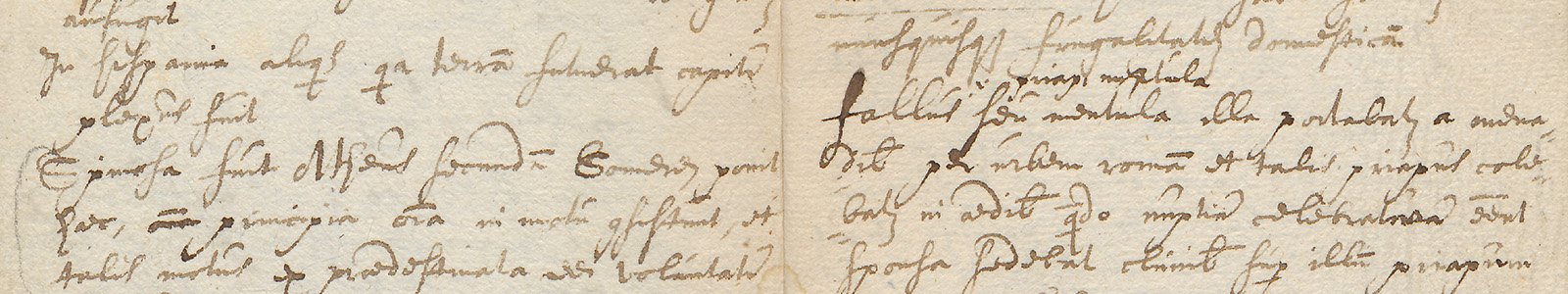

Another point of interest is the total lack of any editiorial interventions in the manuscript. The author scribbled most of the entries spontaneously. The text suggests a more or less continuous flow of impulses, without a fixed, premeditated structure. Literary and philosophical quotations and excerpts alternate with gossip and current affairs in local, national and international politics, as the following exemples from the edition show:

- 163. Roterodami cum paranymphus essem, vidi per microscopia domini Harsoecker semen humanum constare totum ex bestiolis viventibus, gelijk de swarte padde of dingentjes met startjes int water: semen gallorum ac volucrium constat ex Anguillis ac vermibus.

When I was best man in Rotterdam, I saw through the microscopes of Mr Hartsoeker that human semen consists wholly of tiny living creatures, like the black toad or little things with tiny tails in the water: the semen of cocks and fowl consists of eels and worms.

- 60. Ex terbrugh, Itali trajectensem Papam Adrianum vocarunt papa Coglioni, quia dimittebat amicos suos cum exiguo viatico.

From Terbrugh: The Italians called pope Adrian VI from Utrecht Papa Coglioni (Pope Dickhead), because he sent his friends away with a paltry amount of travelling money.

- 100. Casaubonus habebat ante nomen Johannidis aut alterius cujus significationis, sed cum Italia in diversorio, penem erectum ancillae dedisset in manum illa dixit a cazzo buono Casaubonus hoc aliis narrans, inde postea Casaubonus nactus est.

Initially Casaubon had the name of Jones or another of similar import, but after he had put his erect penis in the hand of a maid servant in a tavern in Italy she said: Ah, what a catch-all boner (a cazzo buono). Hence Casaubon, who told this to others, afterwards received the name of Casaubon.

- 98. Ex heinsii opinione eva ab Adamo pedicata est et verso corpore subacta et hinc peccatum hoc et mala omnia fluxere.

According to the opinion of Heinsius, Eve was buggered by Adam and taken from behind, and hence arose this sin and all evils.

- 70. Prins Willem de groote uyt Nassauw gesproten / die is het ontschoten / en staet nu confuys, dit heeft hem verdroten / en klout hij sijn kloten met beijde sijn poten / en komt ons so tuys.

It eluded Prince William the Great, descended from Nassau, and now he stands bewildered. It grieves him, and he scratches his bollocks with both his paws, and this is how he comes back home to us.

Anti-Orangism

The notebook also deserves further study as a source for the history of political and intellectual life in Utrecht in the years following the seizure of power by William III. The anti-Orangist sentiments of the author are remarkable. This political stand is underrepresented in sources dating from after 1674, for the obvious reason that it was inconvenient for anyone with ambition to express their dislike of the Prince in public. A careful reconstruction of the author’s network of kindred spirits would cast light on the presence of a countercurrent in political life in Utrecht, as distinct from the mainstream dominated by the figureheads of William.

Authors

Piet Steenbakkers, Jetze Touber en Jeroen van de Ven, November 2012