'Inscriptiones Urbis Romae Latinae'

From Mantua to Utrecht

Ms. 764 of Utrecht University Library is a remarkable work. It contains the texts of classical Roman inscriptions, written in a careful hand and with subtle decorations. The magnificent title page and binding with imprint are eye-catchers as well. Apparently, much information was already known about this Italian humanistic manuscript. However, on second thoughts matters are more complicated than was thought.

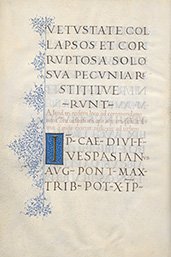

Riddles

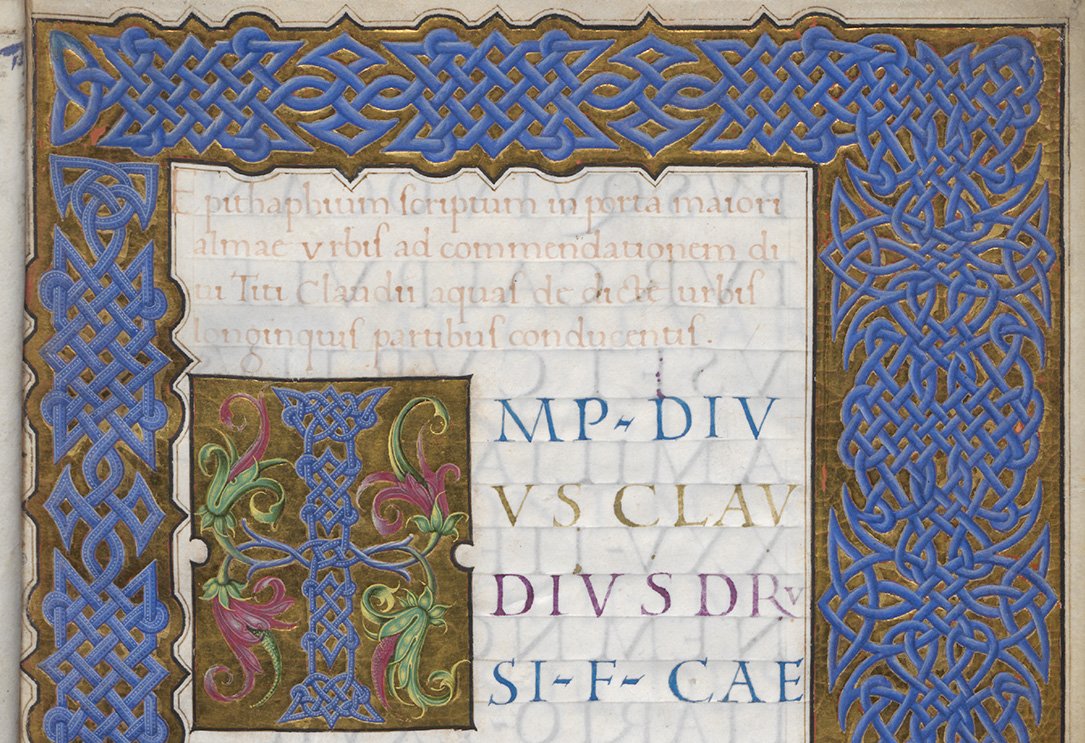

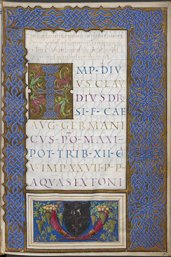

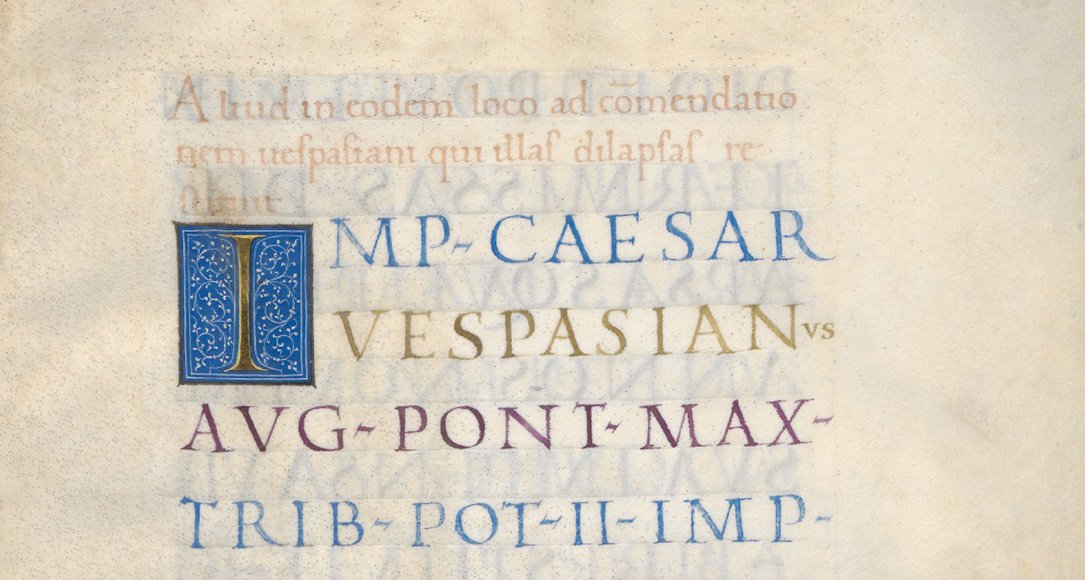

When we open the manuscript at the title page we see a Latin text in colourful capital letters, with an introduction in humanistic minuscule. The initial and the margins consist of blue geometric patterns between gold leaf. At the bottom of the page is a rectangle with a family coat of arms, the identifying mark of the first owner. Also on the front and back of the binding we find coats of arms, abbreviations and heraldic mottoes. Enough clues to identify the text and the history of the manuscript, yet some riddles still remain to be solved.

Epigraphic tradition

The texts in the manuscript are mainly written in the classical Roman capitalis quadrata as they are transcriptions of inscriptions on Roman monuments, most of them from Rome. The modern title of this epigraphic collection is Sylloge Signoriliana, named after Niccolò Signorili. Commissioned by pope Martin V (1417-31) he wrote a collection of ancient Roman privileges and rights around 1430 titled De iuribus et excellentiis urbis Romae. The oldest well-known manuscript is Subacio, Bibliotheca di Santa Scolastica, Archivio Colonna II.A.50, a sloppy copy of which the paleographic date lies between 1430 and 1450. It includes the epigraphic sylloge (collection). An extract from De iuribus, including the epigraphic sylloge, but supplemented with other texts focusing on Rome’s ancient history (antiquitates), has been handed down separately as the Descriptio urbis Romae eiusque excellentiae. The oldest extant manuscript of this text is Vaticaan, Codex Chigiano I.VI.204, which belongs is paleographically dated to the first half of the 15th century.

Attributions

In the past the text of the Descriptio was wrongly attributed to the Roman populist leader Cola di Rienzo (c. 1313-54) (Silvagni 1924). There is also confusion about De iuribus and the Descriptio. Many historians were put on the wrong track by this (see Spring 1972, 175-188, 218-223). The theory that there were two recensions (versions) before Signorili included a third in his De iuribus (cf. Van der Horst 1984, 249) is not correct. In fact there were only two reviews. The first was compiled in the Vatican, Codex Barbarnini Latinus 1952, fol. 170-175. A slightly adapted version with some supplements was used by Signorini in the Descriptio and De iuribus. This means that he was not the compiler of the first recension which partly overlaps a similar collection by Poggio Bracciolini (1380-1459). Poggio’s work, or that by his circle, appears to be the basis of the Sylloge Signoriliana. That is why Peter Spring (1972, 223) suggests to call the text no longer Sylloge Signoriliana, but to name it after the manuscript with the first recension Sylloge Barberiniana.

Older lists

However, the Sylloge Barberiniana is no original list either, but for at least a part of it, it goes back to lists from the early Middle Ages, as they can be found in in Einsiedeln, Stiftsbibliothek, Codex 326 from the late eighth or early ninth century (Welser 1987; Bauer 1997) and in London, British Library, Ms. Add. 34758 from the late fourteenth or early fifteenth century (Petoletti 2003; Buonocore 2015, 26-27; see also Cartwright 2009).

Individual tradition

The epigraphic sylloge of the Sylloge Signoriliana is also handed down in individual manuscripts. The standard edition from 1876 (CIL VI.1, p. xv-xxvii) does not elaborate on this, and how Ms. 764 fits in with the textual tradition of the Sylloge Signoriliana is still open to research. Yet it is safe to assume that this is the most beautiful known copy. However, the origin of the manuscript is not so clear-cut as was suggested in the past.

A silver coat of arms

The coat of arms on the title page was originally made of silver leaf, but has turned black through oxidation. In the four quarters around the red cross in the middle the eagles are nevertheless well visible. This coat of arms can also be found in another manuscript, written in 1477, Vaticaan, Vat. gr. 1626, with the Greek text of Homerus’ Ilias. On fol. 1v and 2r the coat of arms is crowned by a cardinal’s hat and on either side we see the horn of plenty, even though it looks different from the one in Ms. 764. It is the coat of arms of Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga (1444-83) (e.g. De la Mare & Nuveloni 2009, 258-261), and it has always been thought that Ms. 764 was made for him too (cf. Van der Horst 1984, 247-249; 1989, 48).

The Gonzaga family

The cardinal came from an illustrious Italian family. Ludovico I Gonzaga (1268-1360), a friend of the humanist Petrarca, was the first of the family who started to dominate Mantua. Situated between Milan and Venice, the city had to deal with its two powerful neighbours. The Gonzaga’s did so by occupying influential worldly and clerical posts, as did Francesco, the second son of Ludovico II, marquis of Mantua. He studied in Padua and Pisa, got a position in the Vatican, and became a cardinal at the age of seventeen. This opened roads to other clerical jobs on the side, and soon Francesco became an important and wealthy man who also loved art – he is depicted in several works of art. His unexpected death in 1483 is thought to have been caused by drinking contaminated water.

Cardinal or marquis?

After Francesco’s death his art collection was scattered (Brown, 1989) and his books were sold. A large part was acquired by his brothers of whom Federico (1441-1481) had become the marquis of Mantua in 1478. The books were housed in the large Gonzaga library in Mantua (Meroni 1966, 59-60; Clough 1972, 51-52). An inventory of Francesco’s books is in the Archivo Storico Diocesano di Mantova, Curia Vescovile. Federico himself had manuscripts made, such as a copy of Paolo (Florentini) Attavanti, Historia urbis Mantuae Gonzagaeque familiae, now Mantua, Biblioteca Comunale, A IV 18, which is dedicated to him. The coat of arms on the initial page of the text is the same as the one of Francesco, only without the cardinal’s hat (Meroni 1966, 63; Tav. 118) - although the hat also returns in another manuscript which is also dedicated to Federico, a copy of Cataneo’s Epicedion, now Ms. 496 in the library of Holkham Hall in Norfolk (Meroni 1966, 63, Tav. 120; Clough 1972, 54 no. 4). In other manuscripts of both Francesco and Federico and other family members the same coat of arms of Gonzaga keeps turning up, with or without cardinal’s hat (see the illustrations in Meroni 1966 and Gough 1972). So judging by the coat of arms alone it is difficult to determine if Cardinal Francesco, Marquis Federico or even another family member was the first owner of Ms. 764. Further research into the coats of arms, the decorations and the background of the text may give some decisive answers on matter.

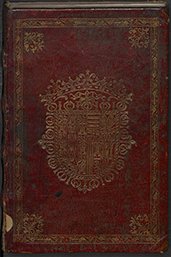

The stamps on the binding

Also on the front and back of the binding we see a very large crowned coat of arms, stamped in gold. A banner contains the letters FEI and around the family coat of arms there is a series of letters. At the top right in the coat of arms we again see the Gonzaga coat of arms, but it is only part of a much larger whole with several coats of arms. On the back is another illustration, a starry sky over the earth with three plants and the motto REVOLVTA FOECVNDANT. This binding is not from the period of the first owner of the manuscript, the late 15th century, but dates back to a later period.

At the front we see the coat of arms of Ramiro Núñez de Guzmán (c. 1600-1668), duke of Medina de las Torres and the Spanish viceroy of Naples from 1637 to 1644. On the back we see the coat of arms of his second wife, Anna Caraffa (1607-1644), duchess of Sabbioneta, and descendant of Isaballa Gonzaga.

The abbreviation FEI means ‘Fortuna etiam invidente’ and the long abbreviation ACGDDMMAHPPMIGPCL stands for Addidit Comitatui Grandatum Ducatum Ducatum Marchionatum Marchionatum Arcis Hispalensis Perpetuam Praefecturam Magnam Indiarum Cancellariam (tuam) Primam Guzmanorum Lineam’, at which the last C and G are in reversed order. The titles refer to the positions that Ramiro’s father Gaspar de Guzmán y Pimentel (1587-1645), the counsellor of king Filip IV, had taken up (Ortiz de Zúñiga 1796, 388; Scharf 1843, 33-35; Miola 1918-19; Walpole Galleries 1926, 105-6, nr. 595; Oldham 1943, 120).

Sale

When Ramiro returned to Spain in 1644 he took a part of the library with him. After his death the complete library was bought by William Godolphin (1635-96), the English ambassador for Spain.

But because ownership marks are missing in Ms. 764, it is more likely that it stayed in the library of Anna Caraffa in Naples. After her death most of her books went to the Biblioteca dei Girolamini and the Biblioteca Nazionale in Naples. But a part was put on the market and that is how Ms. 764 found its way to the Dutch Republic.

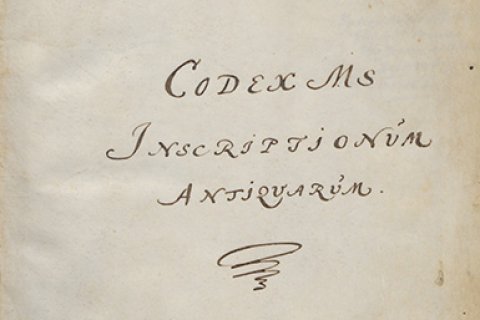

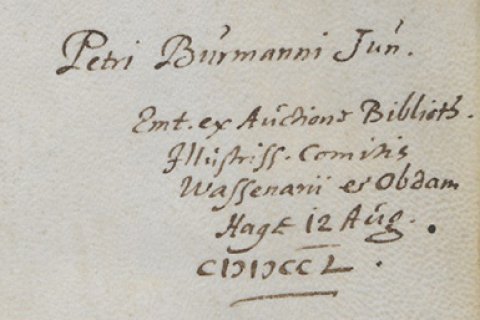

For 23 guilders

In 1750 Ms. 764 was sold at the auction of the library of count Johan Hendrik van Wassenaar-Obdam (1683-1745) (Catalogue 1750, p. 61 nr. 791). It is possible that it had already been part of the library of his father (cf. Roodenburg 2010, 133-4). The purchase was recorded on one of the flyleaves by the new owner, Petrus Burmannus the Younger (Secundus) (1713-1778), Professor of Classical Languages in Amsterdam. He was also the owner of another collection of Roman epigraphy, an autograph of Michael Fabricius Ferrarinus (died 1488x1493), now Utrecht, University Library, Hs. 765. After Burmannus’ death his library was auctioned in 1779, and the manuscript was put up for sale under the title Codex MS Inscriptiones antiquarum which is also noted down on one of the first flyleaves. Ms. 764 was bought by Utrecht University Library for 23 Dutch guilders, one of the most expensive of the approximately 100 lots that were acquired at the time (Miedema 1900, 413, nr. 2412).

Further research

There is still a lot to discover about Ms. 764: to which member of the Gonzaga family should it be attributed? Who wrote it and made the decorations? How does it fit in with the textual tradition of the Sylloge Signoriliana? It must be compared with other manuscripts from that period. Furthermore, it is not clear when it was put on the market after the death of Anna Caraffa, together with other books from her library (which often have the same marks on the binding). And how did it get into the hands of Van Wassenaar-Obdam? This beautiful manuscripts has not revealed all of its secrets yet.

Author: Bart Jaski, May 2019