'Profectus religiosorum'

Act like a monk!

Entering a medieval monastery as a novice was like being introduced to a world unto itself, with its own specific rules and customs. In devoting their lives to Christ, monks were expected to follow Christ’s example and distance themselves from worldly temptations, which were of course lurking behind every corner. Even everyday matters, including how one interacted with other monks or performed duties, were subject to rules of conduct. Various texts were published to help novices prepare for their new life. One such text was written by David of Augsburg (d. 1272), a prior in a Regensburg Franciscan monastery in 1240. This text, the Profectus religiosorum, was like a textbook for monks. Might this typically medieval work have something to offer contemporary readers?

The Profectus religiosorum

The Profectus religiosorum consists of three volumes. The first describes the way of life of novices, focussing on outward behaviour both inside and outside the monastery walls. The second volume relates to inner behaviour, i.e. reshaping the novice’s relationship with himself. The third volume takes an in-depth look at the seven deadly sins. The book was extremely popular – clearly it satisfied a real demand. Hundreds of medieval manuscripts of the Profectus religiosorum have survived. In some cases, the second and third volumes were separated from the first.

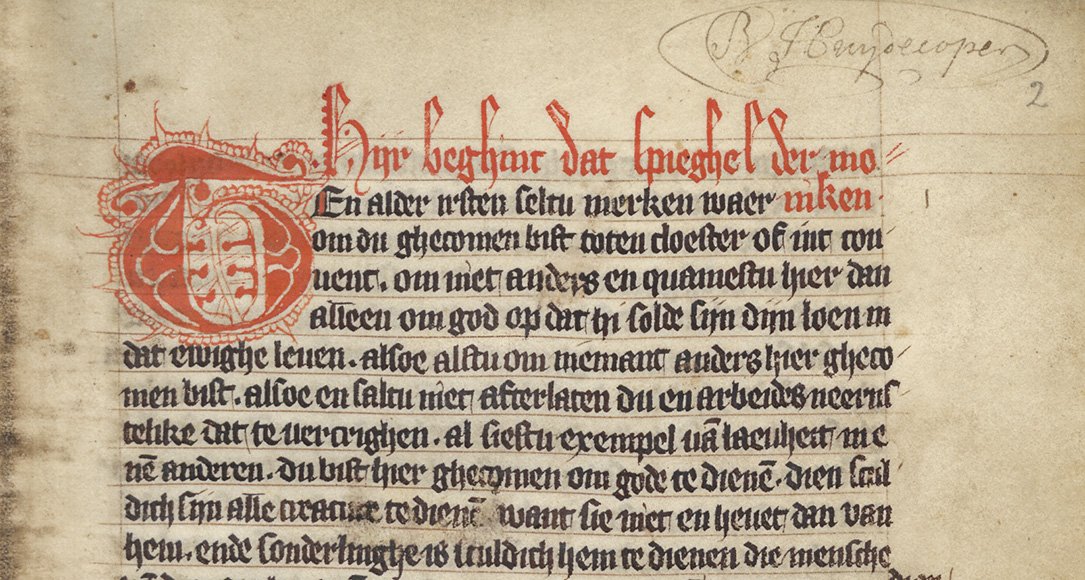

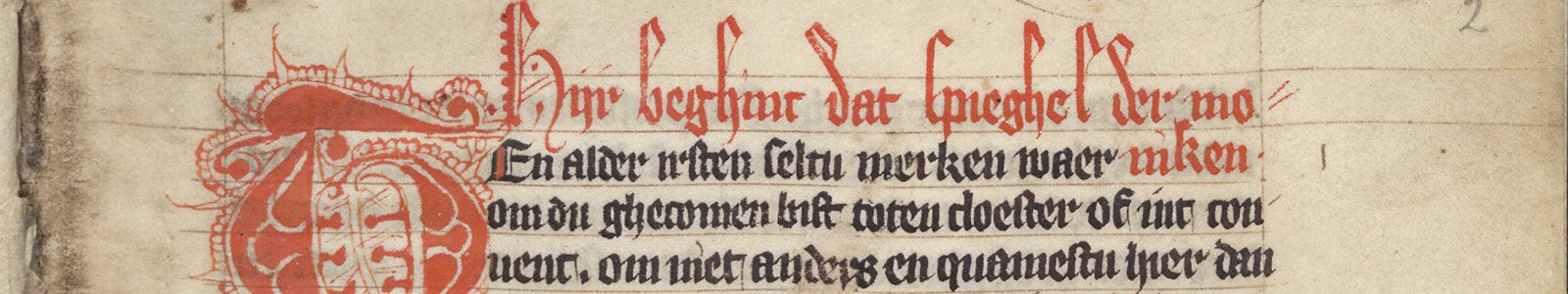

The book was also popular with the Devotio Moderna. Common people who chose to live a pious, communal life, benefited greatly from David of Augsburg’s guidelines. Once the Profectus religiosorum had been translated into the vernacular, it could easily be read by common people, who were often literate, but not always proficient in Latin. The first volume, called Spiegel der monniken ('Mirror of the Monks') has been preserved as a separate text in six manuscripts. Volume one is included with the other two in three manuscripts, of which the manuscript in the Utrecht University Library (Ms. 1020) is the oldest. This manuscript is the second Middle Dutch translation. As regards the second and third volumes of that manuscript, Ms. 1019, which was written in 1403, provides the earliest evidence of the second Middle Dutch translation.

Act like a monk!

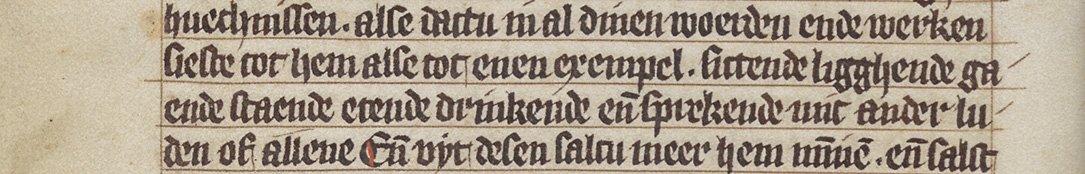

Spiegel der monniken offers medieval novices a wealth of practical information, with guidelines for social interaction befitting a monk. However, many of the recommendations and warnings relating to social interaction are universal and are familiar to contemporary readers. Living by Christ’s example is the book’s basic premise, and it advises readers to: Scrijf in diner herten sine woerde, sine zeden, ende sine werke ('Write down his words and his morals and his works in your heart'). These ideas are applied to all aspects of behaviour: in al dinen woerden ende werken sieste tot hem alse tot enen exempel: sittende, ligghende, gaende, staende, etende, drinkende ende sprekende mit ander luden of allene ('In all your words and works, regard him as an example: sitting, lying down, going, standing, eating, drinking and speaking with other people or alone').

They even applied to daily chores, which were not to be shunned, and included, ymbodel van den huse ende die vulnis uyt den huse te draghen, ende der broders rocken te reynigen van den wormen, of hoer voeten te wasschen, ende boven al gheerne den sieken te dienen ('carrying the furniture of the house and garbage out of the house, and cleaning the brothers' clothes from worms, or wash their feet, and above all joyfully care for sick persons'). All spiritual persons are expected to be devoet wesen in den bedelhuys. In den capittel warachtich. In den reventer (eetzaal) matich. In den dormiter (slaapzaal) rustich. In den ghedachten suver ('devout in the beggar's house, truthful in the chapter, in the refectory modest, in the dormitory quiet. In thoughts pure'). The rest of the text explains these guidelines in detail.

Guidelines for conversation

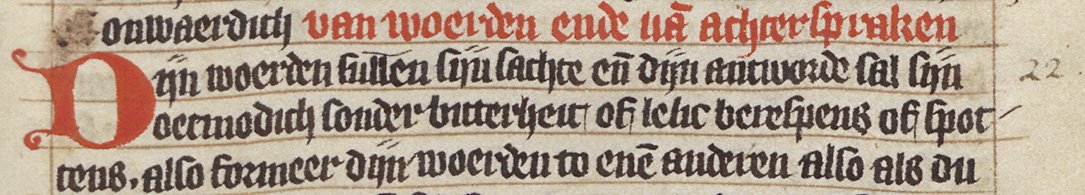

Following Christ’s example meant giving up bad habits, so gossip, slander and angry outbursts should be avoided: Dijn woerden sullen sijn sachte ende dijn antworde sal sijn oetmodich, sonder bitterheit of lelic berespens of spottens ('Your words shall be soft and your answers shall be humble, without bitterness or nasty rebukes or mockery').

Although the book warns of den afterclap ('the gossip, lit. behind-talk'), it also condemns telltales: hoet di also als dattu after niemans rugghe en spreecste. Also meld niet den afterspreker den ghenen daer hi van spreect, opdat hi gheen quaet vermoghen en crighe op den achterspreker ('beware that you don't speak behind anybody's back. So do not tell about the one who gossips to the one's he's gossiping about, so that he does not get a bad opinion of the one who gossips'). No matter what he is thinking, a monk must not pour out his thoughts like een vat sonder decsel ('a vessel without a lid'), but speak purposefully and avoid arguments, anger or arrogance at all costs: Ydele woerde, vlie overal daer sie sijn ('Vain words, flee from wherever they are').

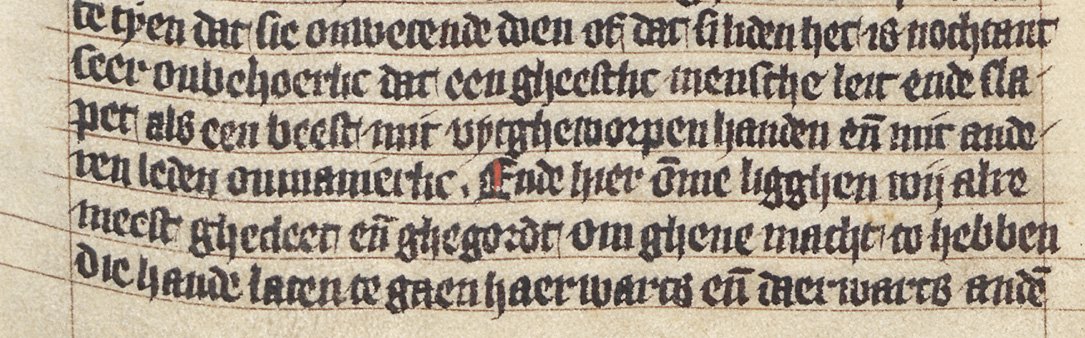

Good posture

The Spiegel der monniken also covers proper carriage. For example, while seated, the monk is cautioned: reec dijn been niet verre uyt ende sunderlinghe als ander menschen daer bi sijn ('do not extend your leg too far and in a curious position if other people are present'). Even in his sleep, unconscious of his actions, he was expected to obey these rules. It is nochtant seer onbehoerlic dat een gheestlic mensche leit ende slapet als een beest mit uytgheworpen handen ende mit anderen leden onmanierlic. Ende hier omme ligghen wij alre meest ghecleet ende ghegordt, om ghene macht to hebben die hande laten te gaen haerwarts ende daerwarts an den naecten lichaem ('however very inappropriate that a spiritual person lays down and sleeps like an animal with hands flung aside and with other limbs in an imprudent posture. And this is why we lay down mostly with clothes on and girded, that the hands don't have the possibility to go to and fro on the naked body'). So keep your hands to yourself, but do not touch yourself either!

The dangerous world outside

As if maintaining proper decorum and leading a virtuous life were not difficult enough inside the monastery, the outside world presented even greater dangers. Het is dicke beter enen gheesteliken menschen in den hues te bliven ende verhudet te wesen van den menschen, dan uyt te gane ende ondert volc te wesene ('It is much better for a spiritual person to stay indoors, and to avoid people, than to go out and be among folk'). A preoccupation with the outside world, maket laeu die vuricheit des gheestes ende maect weec den sterken willen der doegheden ('cools the spiritual fierceness and weakens the strong resolve of the virtues'). And of course, the greatest danger outside the monastery were: women (wiven)! The monks received the following counsel on the opposite sex: Hoet dij als du mit wiven sprekest dattu sie niet vlitelic an en sieste, noch bider hant en nemest, noch niet te na en sittes, noch lichtelic toe en lacheste, noch mit hem en rimest, noch en soekest hueken mit hem te spreken ('Beware when speaking to women that you do not look at them too eagerly, take them by the hand, sit too close to them, smile at them lightly, make verses (poetry) with them, or look for a corner to speak with them'). Apparently, the preferred strategy was avoidance; despite the best of intentions, nochtant somighe menschen solden quaet vermoeden ('nevertheless, some people may suspect evil').

From the convent

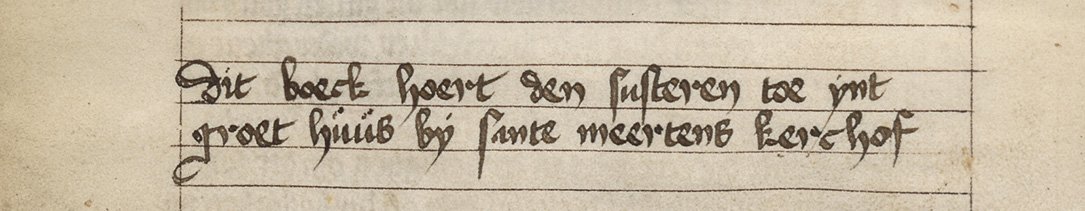

Medieval religious literature commonly alerts to the dangers of women. Sections of the Spiegel der monniken on the subject were not modified, despite the fact that the text, and the Profectus religiosorum as a whole, were frequently used in convents. The same is true of Ms. 1020, of which mark of ownership reads: Den susteren ynt groet huus by sante meertens kerchof ('The sisters of the Great House at Saint Martin's churchyard').

It is the only known manuscript of the sisters of the Grote Huis convent near Martinikerkhof square in Groningen. The manuscript passed through several hands before coming into the possession of the man of letters Balthazar Huydecoper (1695-1778). At the 1779 auction of Huydecoper’s collection the manuscript was sold to the Amsterdam lawyer Hendrik Calkoen (1742-1818), who between 1782 and 1792 passed it on to literary scholar Nicolaas Hinlópen (1724-1792) from Hoorn. In 1882, the state archivist in Utrecht transferred the manuscript to Utrecht University Library.

Transcription and analysis

In January 2011 Roel van den Assem, Eefje Been, Afra Boot, Fleur van Geenen, Jelmer Dijkstra, Jorik van Engeland, Jos Guldemond, Ariane Standaart en Else Vondenhoff did an assignment for the BA-course ‘Het handgeschreven boek’ (The handwritten book). They had to transcribe the version of the Spiegel der monniken in Ms. 1020 and make an analysis of the manuscript. Bart Jaski and Marisa Mol edited their assignment for a publication, which was published in Igitur, the digital archive of the University Library of Utrecht, in February 2014. It is the first edition of the Spiegel der monniken to date.

Author: Bart Jaski, 2011, updated February 2014