Plan and profile of Utrecht by Adam van Vianen

Utrecht librarian does his bit for cartography

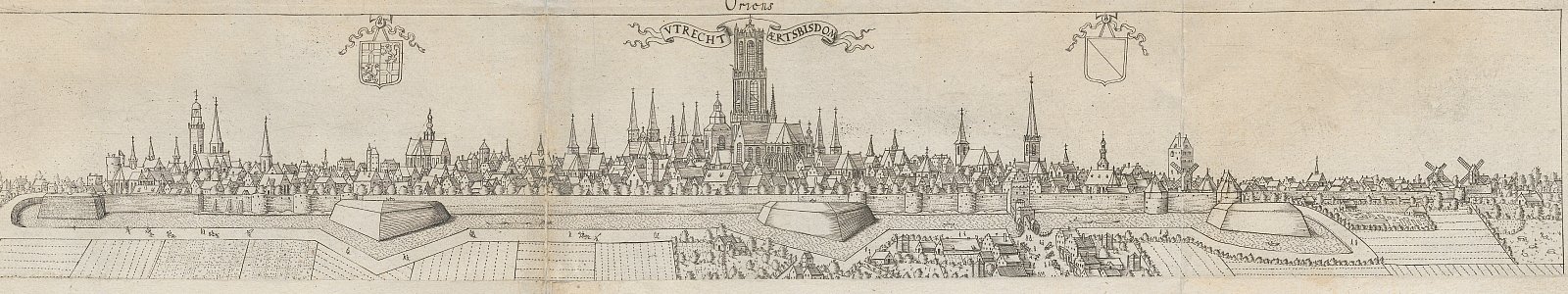

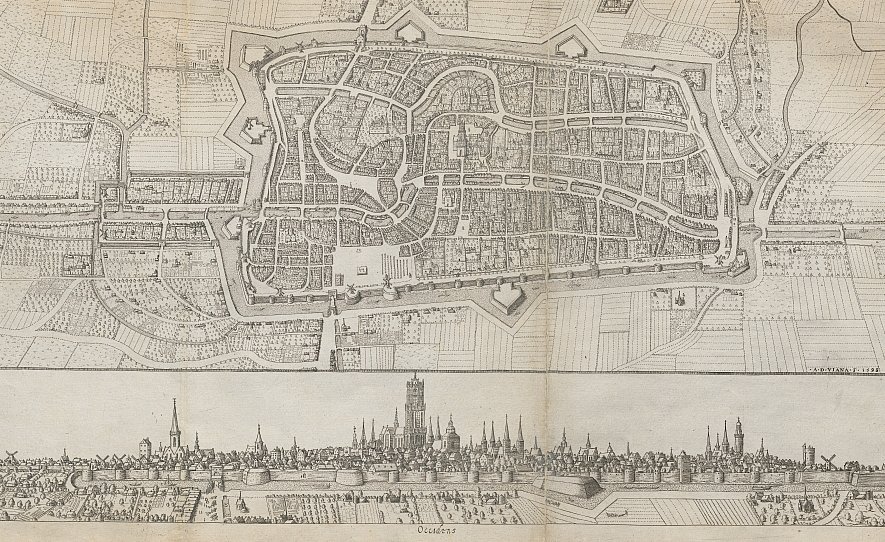

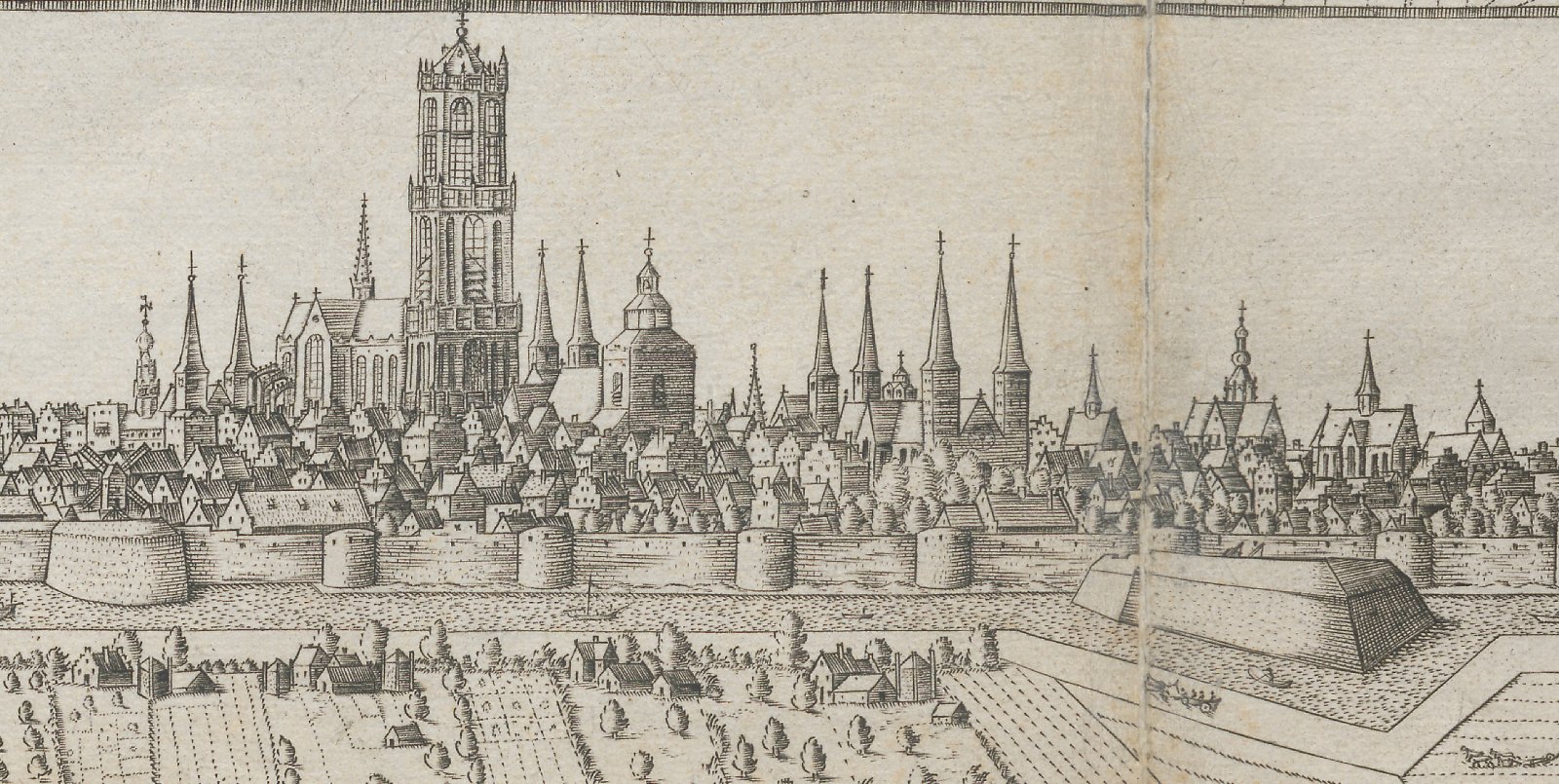

In 1598, the famous engraver and silversmith Adam van Vianen (ca. 1569-1627) published this beautiful map of Utrecht. The map measures 28.5 x 50 cm, including the profile at the bottom showing the skyline of Utrecht at the time, seen from the west (‘Occident’). The map also has a profile of the city from the east (‘Orient’), but it has been cut off this copy and attached to the back.

This map, which is an unaltered reprint from 1651/52 was part of a fifteen-page historical description of Utrecht written by Cornelis Booth (1605-1678), who was the librarian at the time. Even back then, Utrecht University Library was doing its bit for cartography! Booth’s history was a small book, so this map had to be cut to size.

From Roman fort to cathedral city

When Utrecht was founded it was a simple Roman fort. However, during the Middle Ages it grew to become a city. Not only was it the administrative centre of the Northern Netherlands, it was also the bishop’s see. Utrecht held this position until well into the 16th century. At the time, the city had no less than five collegiate churches, four parish churches, an abbey, a beguinage, 24 religious houses and 21 hospitals.

Iconoclastic fury

The Dutch Revolt in 1568 would eventually bring an end to Utrecht as the bishop’s see. Initially the authorities strove towards the peaceful existence of Catholicism and Protestantism side by side. However, as a result of great pressure and terror from strict Calvinists in the form of several outbreaks of the destruction of religious icons, the city authorities forbade the Catholic faith in 1580.

Necessary reinforcement

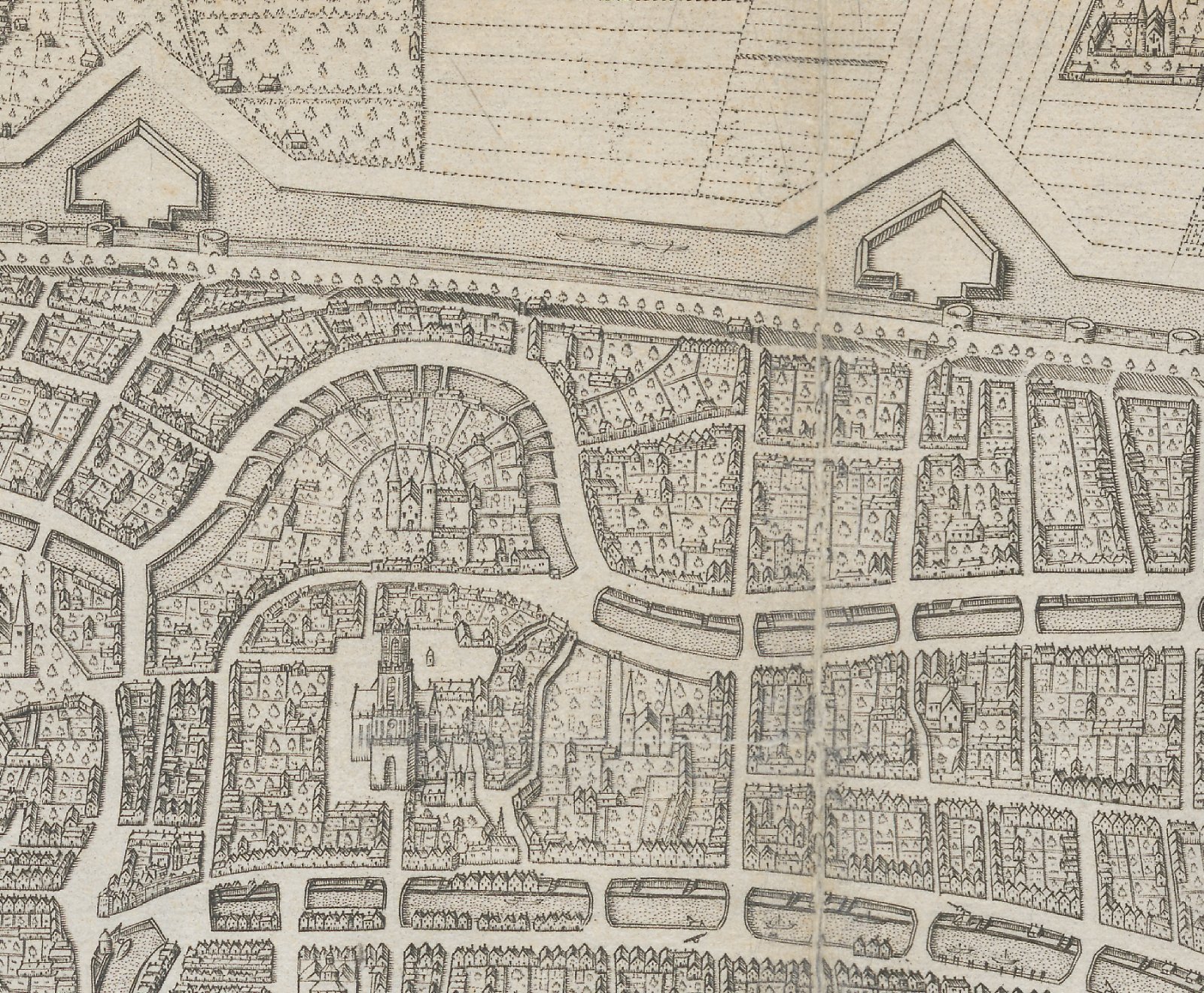

Following the Dutch Revolt and the Protestant Reformation, major spatial developments were carried out as it became clear that the city needed more reinforcement. The medieval city walls, which were worn out and could offer no protection from the new heavier artillery, had already been lowered and protected with earth in the first half of the 16th century. At this time, the first ‘rondels’ or city towers also appeared, although they were replaced by four pentagonal bastions fairly quickly. In 1577, the Eighty Years War led to the further construction of five large earthen bulwarks. These bastions and bulwarks can be clearly seen on Van Vianen’s map.

Destruction of Catholic buildings

The Vredenburg stronghold, on the other hand, was pulled down and this is indeed reflected in Van Vianen’s map: there is an empty space within the city walls at the bottom on the left. The former grounds of the religious houses that were relatively open were used to build houses and lay new roads. For example, Korte Nieuwstraat was laid on the site of the former Paulus abbey and the church of Oudmuster that was demolished in 1586. Many other roads, too, were constructed at the cost of former Catholic sanctuaries.

Errors on the map

There are, however, some obvious errors on Van Vianen’s map. For example, the city is fairly square, yet in reality it is more harp-shaped. Van Vianen probably based the shape on the map by Melchisedech van Hoorn from 1569, which has since been lost. South of the cathedral, the church of Salvator or Oudmunster is also included on the map, as well as in both profiles, despite the fact that this church and its two characteristic spires was demolished in 1587. The Oudwijk abbey is also included, despite its demolition in 1584.

Oldest profiles of Utrecht

Nonetheless, the map and the two profiles give a fairly reliable representation of the city at the end of the 16th century. This is the first map on which profiles of the city were included. It is also the first map of Utrecht that was produced, printed and published in the city itself.

Other, more recent town profiles of Utrecht figure in an attractive and interactive web application named Utrecht in Perspectief ('Utrecht in Perspective'), which is a co-operation between the Utrecht Archives, Kollektief Hic Sunt Leones, and Utrecht University Library.

Permission from the city authorities

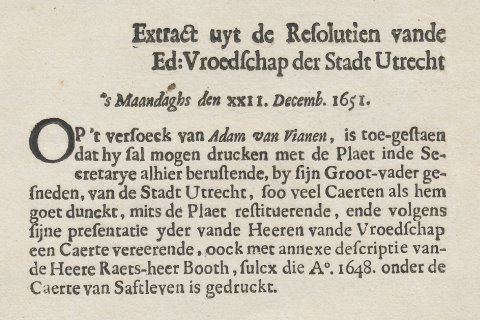

The copper plate map by Adam van Vianen ultimately came into the possession of the city authorities. When his grandson, the surveyor and mapmaker Adam van Vianen, wanted to reprint the map around 1650 he had to be granted permission by the city authorities. 'Extract uyt de Resolutien vande Ed. Vroedschap der Stadt Utrecht ‘s Maandaghs den XXII. Decemb. 1651' is printed on the back of this copy, in which permission is granted, on the condition that the copper plate is returned afterwards. This copper plate is now in the Centraal Museum Utrecht.

Only known reprint in public

To this day, not a single copy has been found of the first edition in 1598. Of the second edition from 1621 Utrecht University Library holds the only known copy in the world. The reprint from 1651/52 has more surviving copies, but is as far as we know only available in public in the Utrecht University Library. The library also possesses the only known copy of the town plan, probably printed between 1652 and 1685. This plan is part of the book Beschryvinge der stadt Utrecht, published in 1685 in Utrecht by Juriaen van Poolsum (MAG: T Fol 210). In addition, several 19th-century reprints of the map have been handed down.

Author