A curious 18th-century atlas of the coasts of Ceylon

Among one of the many professorial collections in Utrecht University Library – that of Gerrit Moll (1785-1838) – is a curious manuscript containing coastal profiles painted in water colours and accompanying texts of Ceylon. Or rather, strictly speaking, it is not a manuscript; the work also contains some printed maps, seemingly cut and pasted from other atlases and books. What is the background of this curious document and what was the purpose of its production?

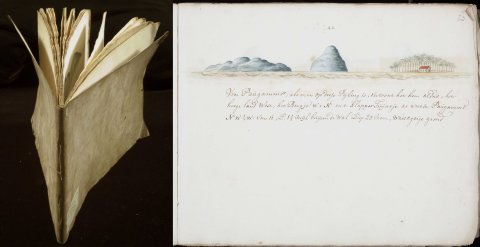

The Utrecht "atlas" of Ceylon is bound in a simple 18th-century binding with cardboard covers. The format is oblong and measures 32 by 40 centimeters. In total, the document consists of 24 pages of purely handwritten texts, 37 pages of hand-drawn coastal profiles – with or without related explanatory notes in manuscript – and seven printed maps of coastal parts of Ceylon.

The title page is neatly calligraphed through the use of auxiliary lines and states Beschryving van de zee-kusten, voornaamste baayen en ankerplaatsen, mitsgaders de daartoe behorenende land-vertooningen van het eyland Ceylon.

An author is not mentioned. A table of contents is also missing, although the text does testify to consecutive "chapters" throughout. The first chapter begins with the coastal description of 'Manaaren' (Mannar Island), in northwest Ceylon. Then, in twenty chapters, it moves systematically southward along the west coast via 'Aripo' (Arippu), Colombo, 'Gale' (Galle) and 'Dondere' (Dondra), among others. After 'rounding' the southernmost cape near the latter place, thirteen chapters go north again along the east coast via all sorts of areas with exotic names such as 'Oliphant', 'Julius' and 'Lage Zandhoek' to 'Arrokgamme' (Arugam), 'Baticalo' (Batticaloa), 'Venloos-Baay' (Vandalous Bay) to finally end at 'Tricoenmale' (Trinconmalee) in Koddiyar Bay. Interestingly, the coasts on the northern side of Ceylon, roughly between Nilaveli and Periayvilankuli, are not described by words and pictures in the atlas.

For the sailor?

Judging purely by the title information of the book – Beschryving van de zee-kusten, voornaamste baayen en ankerplaatsen [...] – it seems to be a kind of navigational atlas or sailor's guide for Ceylon. The handwritten texts and explanatory notes strengthen that suspicion. Coordinates, seabed conditions, depth figures and points of danger to navigation such as reefs, cliffs and sandbanks are given for the various sub-areas. The various areas, linked together as it were by course indications, are also described geographically for the purpose of observations from the sea. The explanatory notes to the coastal profiles also serve the sailor.

Then there are the seven printed maps, cut on the map border and then pasted on the oblong paper. Five of these small maps are fairly easy to trace. After all, these were published in the sixth volume of the Nieuwe Groote Lichtende Zee-Fakkel (1753), the famous 18th-century marine atlas of the Amsterdam maritime publisher Van Keulen. These are overview maps of the southwest and south coasts of Ceylon and of the bays of 'Aproeretotte' (Arugam Bay), 'Venloos' and 'Tricoenmale'.

The maps are coloured and placed near the relevant text passages and coastal profiles. The description of the east coast of Ceylon also includes an uncoloured map of that area, mentioning Joachim A. Trijsz. as engraver. Trijsz. performed engraving work for the firm of Van Keulen in the first half of the 18th century. Finally, the document contains a printed and coloured plan of Colombo, but it is still unclear from which publication it came. However, the style of the plan is consistent with the other coloured maps.

In short, the contents of the book on Ceylon reveal at first glance a function as a navigation guide or atlas for sailors, who sailed the waters around and coasts of the Asian island. But to assess whether this is actually true, it is advisable to first find out its sources.

Provenance of coastal profiles

The atlas of Ceylon was produced with great care and accuracy. This makes it immediately clear that, for example, the coastal profiles were not painted on the spot, but must have relied on a more primary source. At first glance, the 1757 ship's log of Van Schilde and Hoogendorp qualifies. This journal is in the Dutch National Archives and has the handwritten title Vertooning van eylande, custen, havens en baijen ao. 1757 by capt. D. v. Schilde and schipr. P. Hoogendorp (The Hague, National Archives: Aanwinsten Eerste Afdeling, 1.11.01.01 inv. no. 809). The manuscript contains just under one hundred profiles of mainly Asian coastlines, spread over 26 pages.

Most of these profiles – over seventy – cover coastal parts of Ceylon. It requires little imagination to conclude that the profiles in the Utrecht atlas relate to this. The similarities are striking and the explanations of the profiles are also quite similar. Of the 73 numbered coastal profiles, 62 can be traced with certainty to the original ship's log. Only of profiles 1, 12, 29-35 and 47-49 we find no examples.

It is tempting to point to the ship's log of Van Schilde and Hoogendorp as a direct source for the Utrecht atlas of coastal profiles of Ceylon. But on closer inspection that is surely too short of the mark. It turns out that the Leiden University Libraries also possess a manuscript with coastal profiles of mainly Ceylon (Leiden University Libraries, BPL 2030)!

This Leiden manuscript has 85 coastal profiles spread over 45 double-sided written pages; thus, each profile has its own page. The images of the coasts show great similarity to those of the ship's log in the Hague National Archives and the seaman's guide in the Utrecht University Library. These three documents are undeniably related. But what exactly is this "triangular relationship"? It is obvious that the 1757 ship's log of Van Schilde and Hogendorp must have been the oldest source. Presumably the Leiden manuscript is a neat version of the ship's log of Van Schilde and Hoogendorp, with somewhat edited explanatory texts. All Leiden coastal profiles can be traced back to the Hague journal, which is, however, more extensive with some additional profiles of the "Munnikskap" (Mount Friars Hood) and of more distant areas in India, Indonesia and Australia. Over sixty of the Leiden contour drawings subsequently appear to have served as examples for the Utrecht sailor's guide. The captions under those profiles are almost identical. And further, numerous profiles in both documents feature grids, combinations of pencil lines drawn horizontally and vertically.

The riddle of the grids

The Leiden manuscript shows such a grid or square net, drawn with the aid of a ruler, at thirteen coastal profiles. Normally the use of such grids indicates copying practices. Indeed, the thirteen coastal profiles executed with grids correspond exactly to the corresponding profiles in the Utrecht atlas. The latter also contains pencil grids, being identical to the Leiden document.

It appears that the copyist of the Utrecht document had access to the Leiden manuscript and used it to compile his or her own atlas of Ceylon. In general, the more complex coastal views, often with buildings or villages, were copied in this way. The more simple profiles, however, could be copied off the cuff.

Yet this is not the last word on the application of the grids. After all, in the Utrecht sailor's guide there are ten more coastal profiles with a hand-drawn grid. And, strangely enough, those profiles also figure in the Leiden manuscript but without a square grid. Possibly the maker of the Utrecht copy copied the profiles in another way, for example with the help of a square grid on transparent paper? Or are both the Utrecht and the Leiden copies possibly derived from an earlier, still unknown mother copy which in its turn is based on the original ship's log?

However, as regards to the composition of the Utrecht atlas as a whole – besides the Leiden manuscript for part of the profiles and Van Keulen's Zee-Fakkel for the printed maps – it is obvious that another source must have been used. For the book contains another twelve hand-drawn coastal views, many of which show the silhouette of Ceylon's sacred mountain Adam's Peak or Sri Pada (2,243 meters high). Five of these are also characterized by a copy grid. Exactly which source was used needs further investigation.

Textual sources

The copyist of the Utrecht copy further used another source for the rather detailed geographical descriptions and sailing directions of the various sub-areas. After all, these do not appear in the ship's log of Van Schilde and Hoogendorp, nor in the Leiden manuscript. It seems that these texts were largely taken directly or indirectly from the third volume of The English Pilot by the British hydrographer John Thornton (1641-1708). This third volume appeared in 1703 and deals with navigation in Asian waters. In the manuscript atlas of Ceylon, the order of the coasts covered, in chapters, is identical to that of The English Pilot in paragraphs. The translation of the coastal descriptions and sailing directions into Dutch is not one hundred percent in accordance with the English example, but surely based on it. In the interest of a well-flowing Dutch text, this is a somewhat free interpretation of the English original, retaining the actual data of a specific coast such as depth data, bottom features and distances converted to German miles.

Possibly, the creator of the atlas of Ceylon also drew upon the nautical works of the French hydrographer Jean-Baptiste d'Après de Mannevillette (1707-1780), then the foremost innovator in the field of maritime cartography of the East. In his influential Le Neptune Oriental, ou routier général des côtes des Indes Orientales et de la Chine (Paris, 1745) – the first French marine atlas in folio format devoted to navigation to China via the Indian Ocean – the coasts of Ceylon are also covered in words and pictures. The French sailing instructions were also published separately in a book in quarto format, that is, without maps. In detail, some of the data in the atlas of Ceylon correspond to those in Le Neptune Oriental, but this is not surprising since the text in d'Après de Mannevillette's work is a largely revised version of that of Thornton's sea atlas.

Purpose of the atlas

Now for what purpose was the atlas of Ceylon produced? It has already been explained above that the document closely resembles a navigational atlas or sailor's guide. This would therefore betray a function as a maritime tool. Yet this is too easy a conclusion. After all, what interest would the shipping industry of the time have had in a coastal atlas of Ceylon that was both in Dutch and made as a unique manuscript? No, the atlas in itself probably had no demonstrable direct significance for shipping. But indirectly it may have; for the manuscript indicates in a certain sense a design for a printed edition. An indication of this, for example, is the title page which, with its careful use of typography of capitals and ornamental letters, bears the characteristics of a printed title page. Uniform use of frames around the profiles and texts and the inclusion of mounted printed maps further reinforce the idea of a design. However, it remains speculation whether the atlas was intended to be a model for a printed sailor's guide. It is also unclear whether coastal profiles were engraved or etched at all based on the "design". There are no known copper engravings with these coastal profiles, nor, as far as we know, has a printed edition of the sea atlas ever appeared. One hundred percent certainty that the manuscript atlas of Ceylon was or should have been the model for a printed seaman's guide is thus not available. And while there is no such certainty, other options cannot be ruled out either. For example, could the atlas not have been a hobby project of a VOC sailor or Dutch trading post resident with a fondness for Ceylon?

Who was the maker?

The lack of an authorial reference and the uncertainty about the purpose of the production obviously make it difficult to make statements about the potential compiler of the atlas. In terms of provenance, we know that the document must have come into the possession of the Utrecht professor Moll around 1800. What happened to it before that time is unclear except that the atlas must have been made between 1757 – the year of Van Schilde and Hoogendorp's ship's log – and thus around 1800. Based on the hypothesis that the atlas constitutes a design for a printed sailor's guide, some things are plausible. For example, a link with the Van Keulen firm is obvious. After all, this Amsterdam publishing house had a monopoly on maritime cartographic publications in the Dutch language area in the 18th century. Moreover, the printed overview maps in the Utrecht document also come from the house of Van Keulen or point in that direction. That the manuscript atlas never appeared in print may have had something to do with the geopolitical circumstances from the mid-1750s onward. The VOC had long since passed its heyday and had to relinquish more and more trading territories in the course of the 18th century. Ceylon, however, was initially an exception, partly because the Company acquired control of the entire coastline of the island in 1766 through the Treaty of Batticaloa. Could the idea for a Dutch sailor's guide to the coasts of Ceylon have sprung from this? However, Dutch rule over the Ceylonese coasts did not last very long. Beginning around 1780, England also increased its interest in the island, and in 1796 the cinnamon region came into English hands. Perhaps that's why the idea for a printed sailor's guide to Ceylon soon proved outdated and so it remained just a draft? It is a cliché, but again, further research will have to shed more light on this.