The Utrecht Psalter

A unique masterpiece

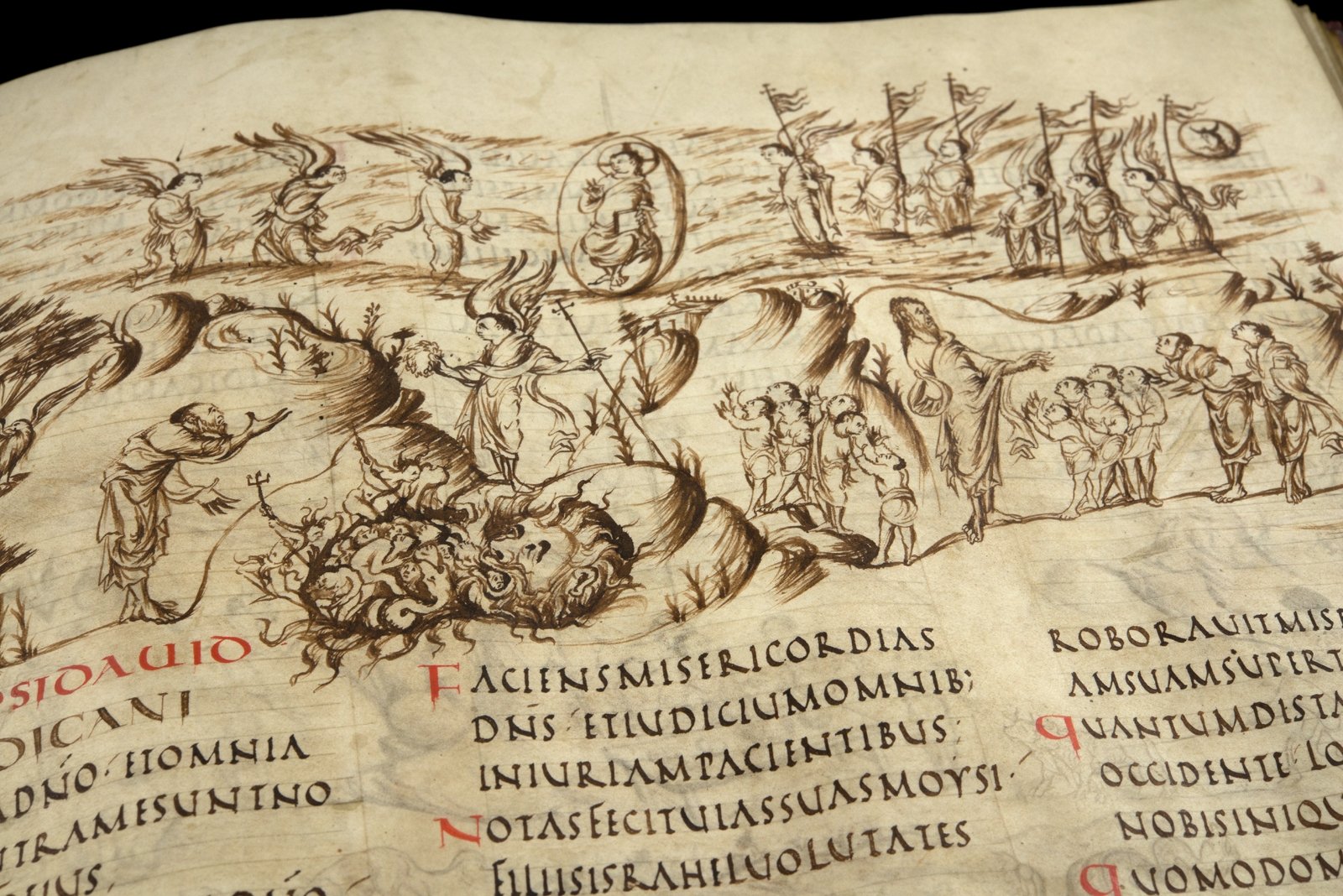

A drawing of the wicked and the sinners, all freaked out. It is a characteristic example of the surrealistic and dynamic style of the illustrations in the Utrecht Psalter. Each of the 150 psalms and biblical hymn texts are richly illustrated with narrative drawings. The Utrecht Psalter is innovative, unique in its kind and a real trendsetter. It was made around the year 830 and it has been kept in Utrecht University Library since 1716. It is the genuine treasure of Special Collections.

Special value

In October 2015 the special value of the Utrecht Psalter is recognised by adding the manuscript to the UNESCO Memory of the World Register for Documentary Heritage. A masterpiece pur sang of which Special Collections is exceptionally proud. In this video you will learn more about the importance of historical material such as the Psalter and why the Utrecht Psalter is on this register.

The first introduction to the Utrecht Psalter does not necessarily mean love at first sight. The manuscript does not expose its beauty and meaning right away. You have to get to know the Utrecht Psalter and only then will it intrigue you. You must learn its story to be able to understand the impact of this amazing manuscript. Many scholars are fascinated by the Utrecht Psalter. The reason? The way in which the 166 psalms and hymns are depicted, and the intriguing composition and style.

Surrealistic style

Probably six artists have worked on the 166 illustrations. Yet their style is relatively unambiguous. It could be described as ‘nervous’, ‘dynamic’, ‘surrealistic’ and ‘baroque’. The pictures sometimes evoke comparisons with the work of Jeroen Bosch. It is the high point of the Reims school from the beginning and the middle of the 9th century, a period in which also other manuscripts and objects were made in this region. Anyone who studies the drawings in detail and links them to the text, will discover how refined and spectacular they are. As a result you will be drawn into the masterpiece.

Revolutionary art

A comparison of the drawings in the Utrecht Psalter with those in other manuscripts from the same or previous periods makes clear how different, innovative and modern they are. It is as if art has made a big leap forward, as if a revolution has taken place in the almost sketch like depiction of the scenes illustrating the psalm-verses. We see buildings, landscapes and heavens, full of kings, soldiers, angels, saints, sinners, craftsmen, musicians, children or a selection from the animal kingdom. Christ, the psalmist or David often play central parts. But also Atlas, the mouth of the Hell or demons with tridents appear on the scene.

Brought to life

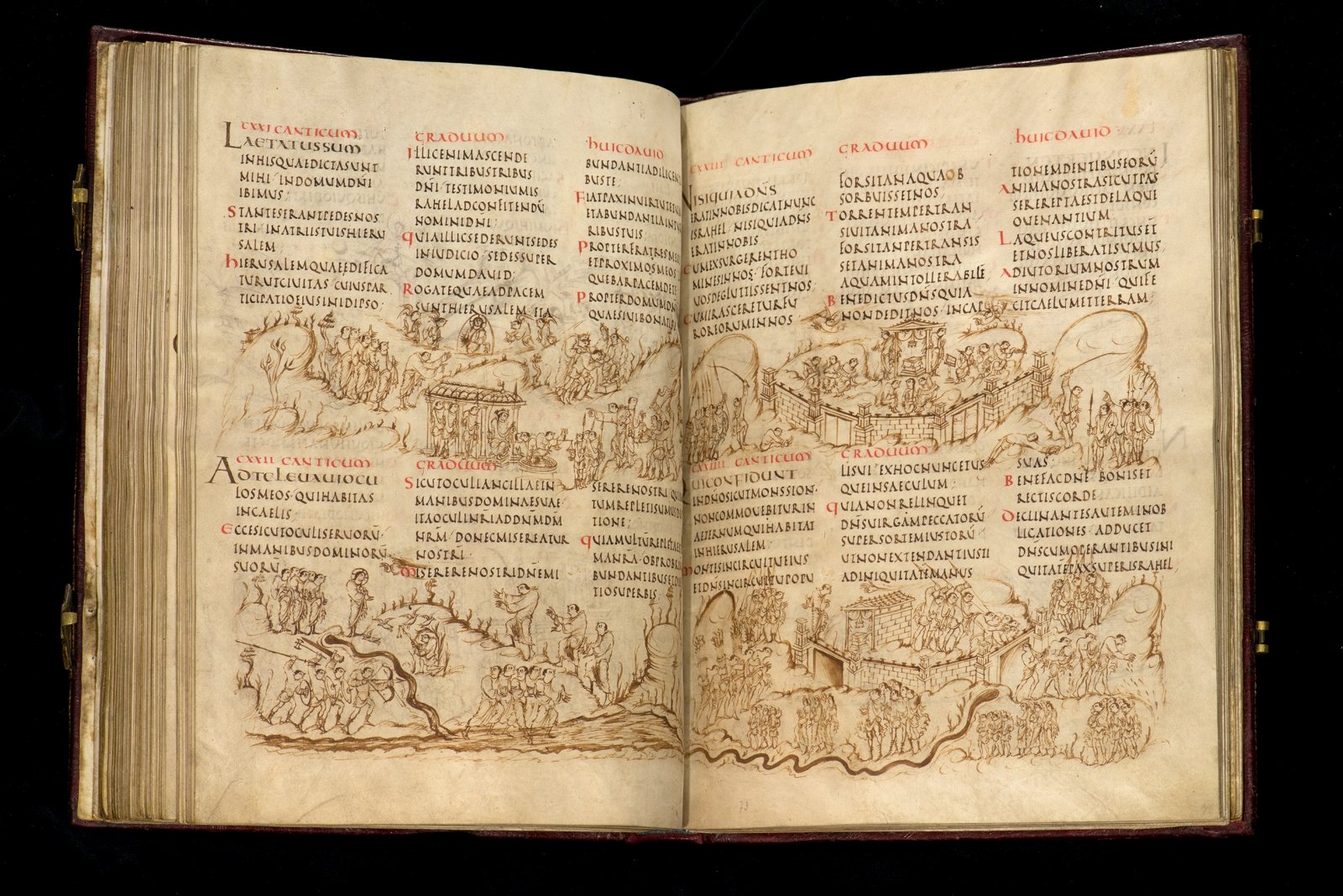

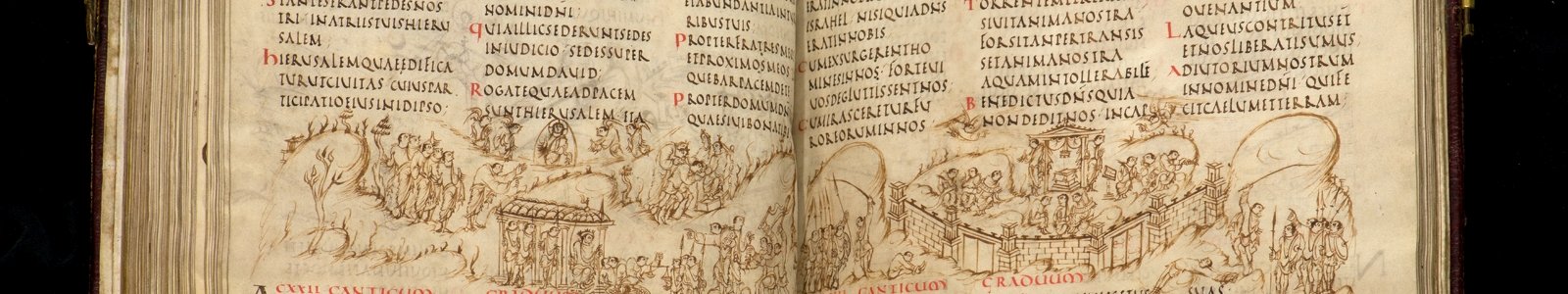

Bringing psalms to life is not the easiest of jobs, because they lack a narrative structure. How were the artists supposed to show the cries for help and pleas of the psalmist to be delivered from his enemies as well as his meditations, his prayers, eulogies and complaints? One of the options was to illustrate the concrete images evoked by isolated words or verses in the psalm texts. The artists of the Utrecht Psalter have succeeded in fully picturing the elements in the psalm texts which allowed and evoked literal illustrations. They combined these illustrations in carefully composed drawings which are across the width of the page above each psalm.

The first psalm pictured

Let us take the first psalm as an example (cf. Van der Horst et al., 1996, 56-57). The text is on fol. 2r and differs in some places from the standard text of the Bible common nowadays. The picture on fol. 1v is the only one which fills the whole page. To the left we see the gloriously happy man (the beatus vir from verse one) holding a book and studying God’s law (verse 2). He does so night and day, as can be seen from the sun, moon and stars above him. He keeps his distance from the sinners who are in the seats of the scornful (in cathedra pestillentiae). These are on the top right and are clearly armed. Small snakes crawl upwards via the right column near the chair. However, the beatus vir is planted like a tree near running water (verse 3) as we can see in the middle left. The lawless are spread by the wind like chaff (verse 4). To the right of the tree we see the wind, personified by a blowing head causing the armed figures in the middle to stagger. They do not survive where God’s law reigns (verse 5) and their road comes to a dead end (verse 6). We see them, helped by winged demons, being driven into the mouth of Hell. They are doomed.

Where, when, for whom and other questions

All 150 psalms and 16 canticles are pictured in this way. The combination of the intellectual program to accomplish this and the innovative and imaginative style make the Utrecht Psalter so fascinating. Scholars naturally wonder who made this, where, when, for whom and why, and where the artists got their inspiration from. These questions have led to a long series of researches, interpretations and discussions. The previously mentioned The Utrecht Psalter in medieval art: picturing the psalms of David from 1996 gives the latest updates in most respects, even though there is still no consensus on the dating and the interpretation of certain illustrations.

Origins

Most experts agree that the Utrecht Psalter was made in 820-830, in Reims or in the nearby abbey of Hautvillers, probably commissioned by archbishop Ebbo. It may have been a gift for Charlemagne’s son Louis the Pious, his wife Judith, or else their newborn son, the later emperor Charles the Bald. Furthermore the late Roman iconography is pointed out as well as the use of the late Roman capitalis rustica as script to show that the illustrations are (partly) based on one or more models from the 5th century. However, there is no question of copying, the illustrations show all kinds of Carolingian elements, interests and interpretations. Some even suspect political messages in some illustrations.

The Psalter moves to England

The Reims style of the Utrecht Psalter, but certainly also the illustrations of certain psalms, remained a source of inspiration for the next centuries, especially at the court of Charles the Bald (d. 877). For reasons still unknown the manuscript ended up in Canterbury around the year 1000 where it was a direct inspiration for the Harley Psalter (11th century), the Eadwine Psalter (12th century) and the Paris (Anglo-Catalaanse) Psalter (12th century). The Utrecht Psalter set the trend and influenced the making of other psalters for centuries to come. A remarkable thing where manuscripts are concerned.

On its way to Utrecht

After the Reformation the manuscript came into the hands of the famous collector Robert Cotton (d. 1631) who had it rebound, and added seven leaves of an early 8th century Gospel from Northumbria, the fragments of an also remarkable manuscript. Also the theft of the Psalter from Cotton’s collection and how it arrived in the Netherlands is a remarkable story. Finally it came into the hands of the Utrecht citizen Willem de Ridder who gave it to the University Library in the Janskerk in 1716. That is why it is called the Utrecht Psalter now.

Controversies

The Utrecht Psalter contains a copy of the so-called Creed of Athanasius which caused a heated discussion in Great Britain around 1870: did this text (also known as Quicumque vult) also belong to the early Christian doctrine or not? If so, it belonged to the Anglican service, even though the text was a thorn in the flesh of many Anglicans, because it was considered too Catholic. The age of the Utrecht Psalter (late Roman or Carolingian) containing the Quicumque vult (fol. 90v-91r) had to give the definite answer. That is why the British government asked the Utrecht University permission for producing a facsimile in London, so that it could be studied more extensively. And so the manuscript was spotlighted. Even though the final conclusion was that the Utrecht Psalter dated back to the 9th century, the Creed of Athanasius kept its place in the Anglican Church. The dispute the manuscript still creates nowadays is mainly battled out among art historians.

Replicas of the Utrechts Psalter

The Utrecht Psalter is one of the first manuscripts that was fully published in a photographic facsimile. This was in 1873, due to the request of the British government. Also as a result, the Palaeographical Society in Londen was founded. In 1932, a new facsimile followed with extensive comments, a facsimile in colour in 1984, a for that time innovative CD-ROM and a new and completely online edition in 2013. Besides several scholarly monographs on the manuscript were published (cf. De Gray Birch 1876; Tikkanen 1903; DeWald 1932; Wormald 1953, Engelbregt 1965; Dufrenne 1978), dozens of articles and the number of publications referring to the Utrecht Psalter amounts to almost a thousand. In 1996 an edited volume appeared on the occasion of the exhibition The Utrecht Psalter in medieval art: picturing the psalms of David in the Utrecht museum the Catharijneconvent. As a matter of course the Utrecht Psalter is included in I.F. Walther, The world's most famous illuminated manuscripts 400 to 1600 (2001). It is also included in standard works which have been read by thousands of students, such as Barbara Rosenwein’s A short history of the Middle Ages (3rd ed., 2009), or Peter Brown’s The rise of Western Christianity (rev. ed., 2013).

A world famous manuscript

The Utrecht Psalter is the most valuable manuscript to be found in any Dutch collection. There is no single other manuscript so much written about and of which so many reproductions have been published, both in print and digitally on the Internet.