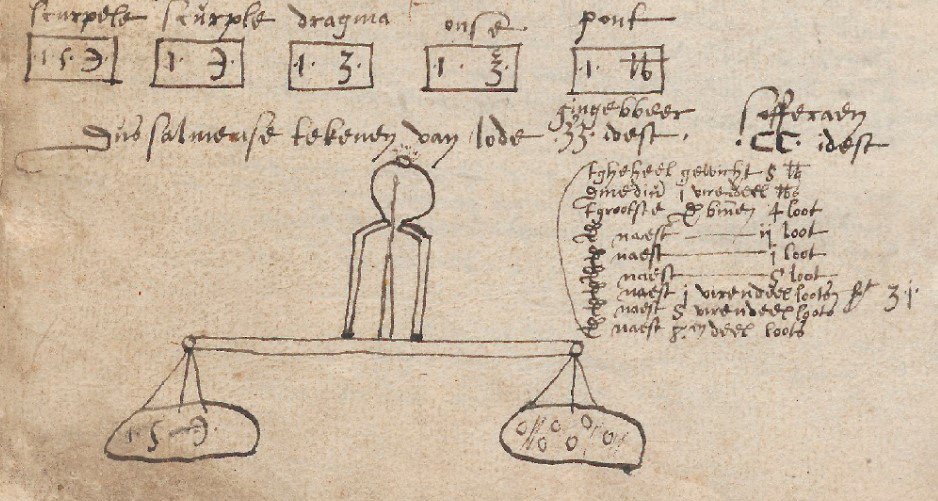

Medical recipes and texts

Medieval medical manuscripts

In this era of health insurance, policy excess, claim forms and supplementary packages it is sometimes hard to imagine what care of the sick looked like in the Middle Ages. The main concern of the surgeons and patients in those days had a purely medical character: how to deal with complicated births, heart palpitations, diarrhea, the plague, cancer, infected teeth or snake bites. Three Middle Dutch manuscripts give us an insight into the medieval world of diseases and medicine. Utrecht University Library has them on a long term loan from the Hattem Voerman Museum. The manuscripts are called Hattem C 3 Hattem C 4 en Hattem C 5.

Bitten by the dog or by the snake

In a surgical treatise in the Hattem C 3 manuscript the question is asked how one can see if the bite of a mad dog or snake is infected or not: Ic sal nemen crumen van broode ende bestrijken dat metten bloede ende worpent voir eenen hont: hij en salt niet eten, ende eet hijt, hij sterft (I shall take some bread crumbs and spread blood from the wound on them and throw them in front of a dog. It won’t eat it, and if it does (and) dies (then it is infected too)).

Treatment with cauterizing irons

If this is the case, the wound must be opened to let it bleed as much as possible. The best thing to do is to use cauterizing irons and stick them all the way to the bottom of the wound. To pull the fenijn (venom) from the wound the liver of the guilty dog is laid upon the wound, or a young chick which is cleft open on its back, or the ash of a burnt vineyard, or salted fish, or opoponax (sweet myrrh) and myrrh, or urine from young children mixed with salt and vinegar. The wound must be kept open for a forty-day period.

Sense of humour

In the treatise it is admitted that many of these wounds are incurable because they attract melancholy in the patient (Braekman 1985, 43-44). This last remark refers to the four ‘humours’ distinguished in medieval medicine. One could be sanguine (too much blood), phlegmatic (too much mucus/phlegm), choleric (too much yellow bile) or melancholic (too much black bile) and as a result possess the accompanying temperaments: cheerful, calm, overactive or melancholic.

Miracle potions

You can also use miracle potions to treat wounds. The author of the largest part of Hattem C 3, Johannes Coninck, writes about the miracle potion of which he had heard from Mark the Jew, and which was suitable for both men and women, whether young or old ‘who have cuts all over their bodies’ . The miracle potion of ‘Master Lowis’ is a herb potion consisting of nearly ten herbs, also suitable for wounds in general. However, in a later addition we read that wounded water-carriers obtain relief from ivy that grows on trees and which wine sellers hang over their doors (Braekman 1985, 16).

Judged to death

The texts in the manuscripts also allow a doctor to make a diagnosis, such as by judging the colour, scent and condition of urine. For instance: als die orine siet oft olie ware ende stinck oft als hij ruck oft riecket als gaer weij: die sal steruen (If the urine looks like oil and smells like ready whey, that one shall die). The author does not mince his words: als t’herte gewont is oft enige groote arterien daer bij, dat is al haestelicx doot (If the heart is wounded included some large arteries, he is as good as dead). The same goes for the diaphraghm or midriff: when the patient suffers from versuchtinge ende swaerhede in die verademinge swaren hoest ende onvergangelijke sweeren in de sijden, dan jugere ic hem de doot (sighs and difficult breathing, coughs and incurable swears in the sides, then I judge him dead), says the author (Braekman 1985, 52).

Boozing in the soup

Also pregnancy is discussed in Hattem C 3, in particular the delivery and the aftercare. First the midwife should check if the delivery is near by feeling the pulse of the woman that has been impregnated. And if the woman is agitated and walks to and fro, with a grim and painful expression on her face, dan eest arbeijt (then labour must be done, pushing must start). But first she has to piss, because the woman may ‘not retain water’. Every eight or ten pater nosters she has to pee, until her water breaks. Then the woman is put in a bath with eleven herbs: mugwort, sweet clover, chamomile, mint, wormwood, rue, savin, St John’s wort, thistle, leek and celery. And in this vegetable soup the woman must drink a syrup with sweet wine. If she cannot take it any longer, she will be dried off and she can walk around the room supported by another person, and one should make her sneeze with hellebore. If the child still does not come, she should take another ounce of syrup with sweet wine. If necessary a plaester, is used, a kind of mushy substance which will be inserted into her female parts: ‘the child will come out whether alive or dead, and even if it is completely rotten, it must be forced out of the belly’ (Braekman 1987, 124-125).

Quackery?

A medieval medical manuscript such as Hattem C 3 contains fascinating literature about the medical practice and theory of those days. Of course it is easy to dismiss the knowledge of the past as non-scientific and superstitious, and the medical world as rough, bloody and painful. It is certain that Johannes Conink and his contemporaries had the theory wrong, but they did work with a focus on the practice of medicine. The texts are realistic and direct and meant to cure the patient. Without regular painkillers or refined medical equipment it did not always work out fine. Some solutions appear to do more harm than good, but only by testing them scientifically we may know if for instance urine of young children mixed with salt and vinegar can cleanse an infected dog bite or not. Maybe we should just put it to the test …

A manual for surgeons and doctors

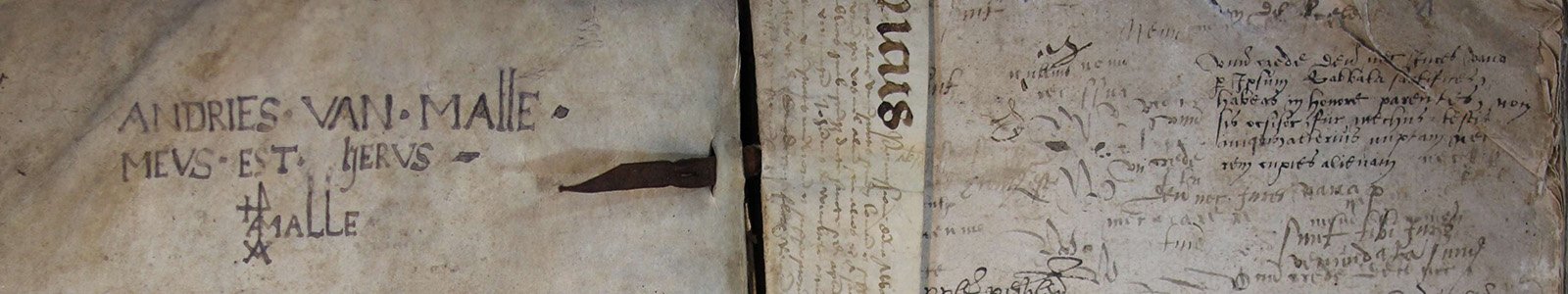

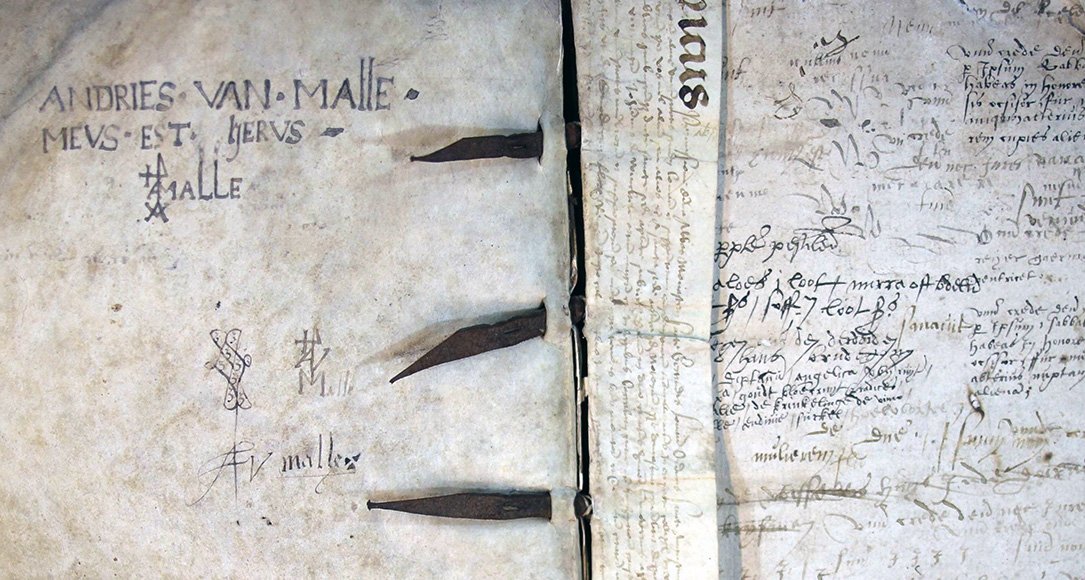

In his edition of the Cirurgia of Hantgewerck int lichame der menschen (Surgery or Handiwork in the body of peoples) Willy Braekman (1985) suggests that Hattem C 3 was compiled by Johannes Coninck. In view of the use of language he places the author in Brabant, in the second half of the 16th century. An act bound as binding material written on behalf of the abbot of the Louvain monastery of Sinte Gertrudis backs up this hypothesis. A later owner was Andries van Malle. On one of the leaves he notes down a lease which tells us something more about his living conditions as a surgeon.

Andries van Malle

In the Antwerpen Poortersboek (Book of Citizens) it says that Andries van Malle, Wynantsonne, surgeon, from Eeckeren (now an Antwerpen neighbourhood) was registered as citizen of Antwerpen on 14 April 1559. This means that we can date back Coninck’s work to the period between c. 1540 and 1560. Several other notes lead Braekman to think that the manuscript was in the vicinity of Utrecht in the 17th century.

From an Antwerp surgeon to the Utrecht nobility

On p. 133 of the manuscript we find all kinds of recipes, some coming from persons (see the text in Braekman 1985, 17). Mentioned are the Lord of Wilp, Lord of Rysenborch, the surgeon of the count of Cuylenborch, and Squire Joost Pieck (van Tienhoven, Lord of Zuilichem, which was sold by his widow to Constantijn Huygens sr. in 1630). Alijt van Bronchorst, Lady of Wilp, is even mentioned several times. She is better known as Aleida van Bronckhorst-Batenburg (1512-1586), wife of Jan van Renesse (1505-1553), Lord of Wulven (Houten), Wilp (near Deventer) and Oud-Amelisweerd (near Utrecht). Their son Jan (1537-1584) married his second cousin Margaretha IV van Renesse van Elderen (1539-1574), the daughter of Jan VIII van Renesse (1505-1561), also lord of Oostmalle (near Antwerpen). Maybe there is a connection here with Andries van Malle.

In the direction of Hattem

The eldest son of Jan van Renesse and Margaretha, also called Jan van Renesse (1560-1620) married Hester van Hattem. One of their grandsons, Alexander Emanuel (1596-1656), bore among others the family weapon of Van Hattem in his coat of arms. He was born in Huize Eerde in Ommen (to the east of Hattem). It is probably via these family connections that the manuscript ended up in Hattem, but more research is needed to give a definite answer. That is also true for the origin of the other two medical manuscripts in Hattem.

The discovery of the medical manuscripts in Hattem

In 2013 it is exactly thirty years ago that the Belgian professor Willy Braekman (1931-2006) revealed the finding of three Hattem manuscripts in the journal Volkskunde. In February of that year the Hattem family doctor Jan Hendrik Sypkens-Smit (1913-2001), who also published about medical history, had brought the manuscripts to the attention of Braekman. They were housed in the library of the museum of the Foundation Oud-Hattem, in Hattem near Zwolle. The museum formerly called Streekmuseum ‘Oud-Hattem’ (Achterstraat 46-48) is now called the Voerman Museum Hattem named after father and son Voerman whose paintings form the heart of the collection.

On a long-term loan

In 2010, on the initiative of the Werkgroep Middelnederlandse Artesliteratuur (WEMAL) Hattem C 5 was brought to the Utrecht University Library to be digitised. At the request of the members of the editorial group it remained in the library as an inspection copy. As the Voerman Museum lacked the facilities to preserve, catalogue and make the other manuscripts available, a decision was made to give not only C 5 but also C 3 and C 4 on loan to the University Library. Formally, however, the manuscripts remain in the possession of the Voerman Museum.

Unknown texts

Soon after the discovery of the manuscripts in 1983 it turned out that the three manuscripts contained a whole series of known but also of unknown texts. They were described subsequently by Braekman (who had gotten them on loan), who also edited a number of texts from them (see also the overview in Jansen-Sieben 1989, 346-350). The three manuscripts date back to the 15th and 16th centuries, and may contain pieces in Latin or French besides the Middle Dutch texts.

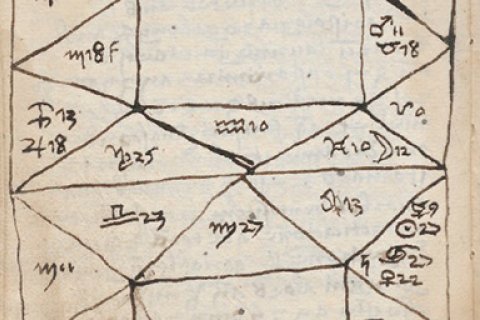

Editions

Hattem C 3, already discussed above, is a much-used manuscript, with all kinds of additions, texts crossed out and torn leaves. Of the 263 pages a little more than 10 percent has been edited, and most texts are not known from other manuscripts. The emphasis is on medical recipes and treatises. Hattem C 4 is a relatively small-sized manuscript (138 x 104 mm) and has 208 pages. In addition to medical recipes and treatises it contains a few texts about astrological disease diagnoses. Some texts are in Latin. Everything was written at different moments in time by the same rather legible hand which is dated in the 16th century. Almost 25 percent of the manuscript has been edited by Braekman in different publications. Hattem C 5 has 562 pages, most of them in Middle Dutch, but there are also some pages in Latin and there are five French texts. The subjects are somewhat broader than the ones in C 3 and C 4, including texts about making brandy and cosmetics. C 3 still has its original binding, C 4 and C 5 have been bound by the same person or firm in the modern age. Further research may shed more light on this matter. We are not done yet with these three patients!