Augustine's 'De Civitate Dei'

Between heaven and earth

Church Father Augustine describes in his De civitate Dei (‘About the City of God’) the conflict between two cities: the earthly city where vanity and power reign, and the city of God, where spiritual power reigns. Augustine wrote De civitate Dei, consisting of 22 volumes between 413 and 426. It was a response to the Sack of Rome in 410. The capture of “ the eternal city” by the Visigoths was God’s punishment, according to Augustine. The work greatly influenced Christian theology and was copied numerous times during the Middle Ages. One of the most beautiful copies is housed in Utrecht University Library.

The city of God

De civitate Dei is a historical-philosophical writing in which Augustine views the history of the world as a battle between those who believe in the love of God and those who focus on earthly matters. The title of the work refers to the two kinds of human communities or cities that Augustine distinghuishes: an earthly city (civitas terrena) and a heavenly city (civitas caelestis). The earthly city represents vanity and power. The city of God is a place where the faithful can form a relation with God and focus on spiritual power which in the end is stronger and more important than worldly power. Both cities are followed in their origin, progress and ending (Dombart & Kalb 1955; Bettenson 1980; O’Daly 1999; Wetzel 2013).

Who is Augustine?

Together with Jerome, Ambrose and Gregory, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis (354-430) was one of the four great Latin Fathers of the Church. Augustine was bishop of the city of Hippo Regius, the present Annaba in Algeria, and in that role he dedicated himself from 396 onwards to the defence of Christianity. Since Emperor Constantine the Great (280-337) Christianity had become the prevailing religion in the Roman Empire. Pagan opponents of the Christian faith considered this development to be the cause of the decline of the Roman Empire by the invasions of 'barbaric' people.

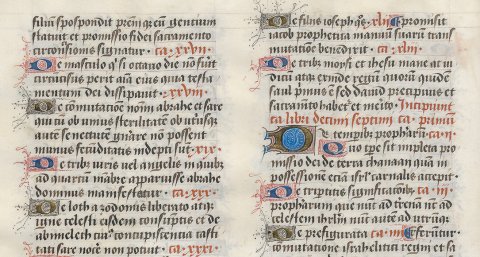

Frequently copied manuscript

De civitate Dei has had a permanent influence on later Christianity, because it makes a clear distinction between the ups and downs in our temporary life on earth and the constant blessings of life in heaven, and because it explains the history of the world from a Christian perspective. In the Latin world, Augustine’s work was frequently copied, translated and commented upon. The Latin versions were used by priests and in cloisters. The Latin copy in Utrecht University Library is special because it comes from a private collection owned by a nobleman, Wolfert VI of Borselen (1433-1487). Dutch nobility usually ordered copies of the text in a French translation, because French was the everyday language of Dutch nobility (Wijsman 2010, 264; Bousmanne & Delcourt 2011, 295-309).

The manuscripts of Wolfert VI of Borselen

We can see that this copy of De Civitate Dei belonged to Wolfert VI because of the coat of arms in he lower margin of fol. 1v Reading such a coat of arms is a science in itself, and it must be analysed in detail to arrive at an exact interpretation. Wolfert VI van Borselen (1433-1487), Earl of Grandpré and Lord of Veere, married Mary Stuart (1428-1465) at a young age in 1444, daughter of James I, King of Scotland. In this way he inherited the title of Earl of Buchan, a title which belonged to the king or queen of Scotland. Both coats of arms were joined together to form a new one: in the first and third quarter the coat of arms of Van Borselen was shown, in the second and fourth quarter we see the coat of arms of Buchan. At the top of the coat of arms a helmet with the ranks of a marquis is depicted (cf. Vennik 1988, 67). The sign of the helmet is a black Dutch hat with a roll in the family colours black and white, adorned with four peacock feathers. As can also be seen in the coat of arms of his father Hendrik II van Borselen (1404-1474) in the Koninklijke Bibliotheek in The Hague (National Library of the Netherlands), Ms. 76 E 10, fol. 81r, the feathers refer to the title ‘Lord of Veere’ which was borne by the family (Conrads & Klinkhamer 1985, 28) (Veer means feather in Dutch). This family coat of arms can still be seen in the town arms of Veere. This town fell under the protection of the lords of Van Borselen who lived in the nearby Slot Zandenburg (De Lind van Wijngaarden 1989, 49 n. 2). The title Lord of Veere has been inherited by the Dutch royal family after 1581 as ‘marquisate of Veere’ (McAndrew 2006, 195).

Wolfert VI was a prominent nobleman with an interest for luxurious books. About a dozen manuscripts owned by him have survived. We know that these manuscripts were his from the family coat of arms of Van Borselen, which is usually put in the marginal decoration. Such a depicted coat of arms is generally a reference to the person who commissioned the work or to the first owner. Most of the surviving manuscripts from his library, such as the Book of Hours of Charlotte de Bourbon (Alnwick Castle, Percy Ms. 492) (Backhouse 2002, 76 ill. III.3), the Ovide moralisé (St. Petersburg, National Library of Russia, Ms. fr.F.v.XIV.1), or the Faits des Romains (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France (BNF), Ms. Français 20312 bis) were illuminated in the Southern Netherlands between the late 1450s and the beginning of the 1480s (Blom 2009, 260-271). This is also true for De Civitate Dei.

Wolfert maintained strong ties with the Burgundian court. One of these ties was with his brother-in-law Lodewijk van Gruuthuse from Bruges, one of the greatest bibliophiles from Flanders, and Wolfert’s predecessor as stadholder of Holland and Zeeland. From Lodewijk’s library the Gruuthuse manuscript (West Flanders (Bruges), c. 1395 – c.1408) survived (The Hague, National Library, Ms. 79 K 10). Gruuthuse owned a De civitate Dei manuscript as well, which was made around 1467 (BNF, Ms. Français 174). It concerns the French translation by Raoul de Presles (1371-1375), councillor of the French king Charles V.This copy was illuminated in the workshop of the Master of Margaret of York where probably also Wolfert's copy of De Civitate Dei was made.

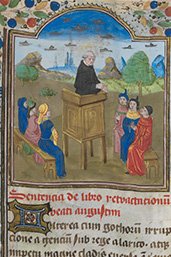

Augustine and the pierced heart

The manuscript is richly illuminated. In the historiated initials we see the development of the Christian city on earth with Augustine as an observer, either on the foreground or in the background. He can be easily recognised by his blue overcoat with red sleeves and blue high hat made of felt. Only in the illumination on Fol. 1 Augustine looks differently. The 21 historiated initials show a preaching Augustine in a black cloak, the garment of an Augustine brother who lives according to the rules of Augustine.

In the next page-filling miniature on Fol. 1v , Augustine dressed in a white alb with red cope shows a male company of philosophers (such as Plato) around in the city of God. In his right hand he holds the episcopal crosier, in his left hand he carries a red, intact heart. This refers to a passage from another work by Augustine, the Confessiones (Book IX, 2,3): ‘Thou hadst pierced our heart with thy love, and we carried thy words, as it were, thrust through our vitals’. So actually, the heart depicted should have been pierced with arrows, as can be seen in many other manuscripts, for instance in the Book of Hours of Catherine of Cleves (New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, Ms. M. 945, fol. 245r).

Augustine shows the company the ideal image of the heavenly city of God. Here the believer may enter after a virtuous Christian life. The garden of delight with a closed-in garden refers to this ideal. Behind the walls of the garden a city with a church, a chapel and the corresponding buildings are represented. Some believers pray piously in front of Christ on the cross or in front of an altar.

Several illuminators?

Scholars suspect that also the miniatures and initials of Ms. 42 were made in the Southern Netherlands. This would be shown by the variations in technique, in which an aquarelle technique is alternated with a thicker layer of paint. Possibly the artist was the Master of Margaret of York, mentioned before, whose main commissioner was Lodewijk van Gruuthuse. The painter was active in Bruges around 1470-1480. The style from the Utrecht manuscript matches the works attributed to him, such as Gruuthuse’s De civitate Dei (BNF, Ms. Français 174) and the Jardin de vertueuse consolation (BNF, Ms. Français 1026) (Bousmanne & Delcourt 2011, 295-309).

In addition, maybe two or three illuminators worked on the illustrations, as the illuminated initials in the manuscript seem to be by another hand than the initials of fol. 1r and 1v. Bodo Brinkmann is of the opinion that fol. 1r and 1v were made by the same illuminator as those of Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, SPK, Ms. Depot Breslau 2 and Bruges, Groot Seminarie, Ms. 154/44 (Brinkmann 1997, 71-73). Due to the build-up of the images with a rich palette of melting colour and light, they strongly resemble one another. Characteristic of the Master of Margaret of York are the well modelled characters (with typically high hats) and the attention given to the horizon with atmospheric perspective in the historiated initials in the rest of the manuscript (Kren & McKendrick, 2003, 218 n. 14; Bousmanne & Delcourt 2011, 308-309).

Between heaven and earth

We like to show you around the manuscript by explaining a few initials which are special in relation to the text. Augustine's work contains several themes, such as evil, happiness, society, the state and historical events which return in the 21 historiated initials.

Book 2 (fol. 16r)

Supervised by Augustine and his company, three masons chisel an inscription into a sarcophagus. On the wall we see a sitting peacock which supposedly refers to immortality (peacock meat does not decay) and the resurrection (a peacock gets new tail feathers every year). This points to the temporality of our earthly existence (Bielermann 2008, 287). The initial relates to the words in the text. It is said that the commandments of the gods must be observed, so that people may lead virtuous lives. In fact, the gods are more like deceptive demons who should be rejected in order to observe the commandments of the true God. Once this is accomplished, the eternal kingdom is yours to enter.

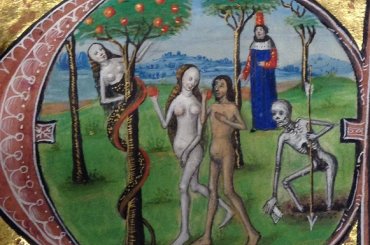

Book 13 (fol. 165v)

Augustine sees Adam and Eve naked in a garden where a snake with a female body (the snake of paradise) twists itself around the trunk of a fruit-bearing tree. From a hole in the ground a skeleton crawls up bearing an arrow as staff in his left hand and a roll in the other hand. This is a depiction of the Fall of man and of Death whose arrow as a symbol of death will hit us all. Probably Eve has already eaten from the forbidden fruit, full of shame she covers herself, while Adam is about to taste it. Augustine’s text discusses the subject of seduction and the Fall of Adam (and Eve).

Book 15 (fol. 190v)

Here the miniaturist compares two murders. With his right hand Augustine points to Cain on the foreground who is holding the head of his brother Abel who is lying on the ground. Cain is about to kill him with a jaw bone. In the background on top of a hill a man with a raised sword will kill the man lying on the ground. This scene refers to Remus killing his brother Romulus. Here Augustine draws a parallel between the Roman tradition and the story from the Bible (Genesis 4:1-16), the two fratricides and the founding of the city of the earthly community.

Book 22 (fol. 325r)

Here, Augustine points to the walled earthly city. Two angels carry souls - wrapped in a white cloth - up to the heavenly Jerusalem. They are the chosen souls who have been given the eternal life by God and now will meet with heavenly bliss. A margin consisting of clouds [LINK] separates the heaven from the earth. Mary and God the Father are watching, in the company of saints with halos and a kind of small devils, the so-called fallen angels. In this last book 22, Augustine discusses the chosen: the inhabitants of the city of God (De Lind van Wijngaarden 1989, 85).

Bruges as backdrop to ‘De civitate Dei’

We have indications that Ms.42 was probably made in Bruges. We know of seven to nine manuscripts of which we may almost safely assume that they were commissioned by Wolfert VI of Borselen. Two of them could come from the workshop of the Master of Margaret of York. Stylistic similarities as to buildings, landscapes and skies also point in that direction (Wijsman 2010, 263). It may well be that Wolfert had De civitate Dei made in Bruges, as he was a frequent visitor of that city because of his important connections (Lodewijk van Gruuthuse, Philip I of Burgundy and Mary of Burgundy). These nobles also had their manuscripts made in Bruges.

In addition, a number of the miniatures in De civitate Dei show medieval buildings which seem similar to still existing remains in contemporary Bruges, which could also be seen in the Jardin de vertueuse consolation (BNF, Ms. Français 1026), also attributed to the Master of Margaret of York. Thus we can recognize from Antonius Sanderus’ Flandria illustrata (1641) the Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk (ill. 114) and the Belfort (ill. 114) on fol. 1v, as well as the Gentpoort (ill. 111) on fol. 98v of Ms. 42. According to Marco van Egmond, curator of the Map Room of Utrecht University Library (personal comment 21 March 2014) it is known that the Belfort got an octagonal Gothic spire in 1482-1483. If it is indeed the Belfort that is depicted in Ms. 42, we may assume that the manuscript dates from before 1482. This matches with the fact that the Utrecht manuscript of De civitate Dei is usually dated between 1465 and 1470. This dating is based on the similarity between the coat of arms of Wolfert I of Borselen and the one on his Valerius Maximus manuscript (Parijs, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, Ms. 5196) (Avril & Reynaud 1993, 256 nr 47).

Because of the heraldry of the joined family coats of arms and the date of the death of Mary Stuart (the first wife of Wolfert VI) the manuscript must have been made around 1465. Later dates of the manuscript are not probable for three reasons; firstly Van Borselen remarried in 1468 with Charlotte of Bourbon. There is now no question of a joint coat of arms, as was the case with his first wife. Also Wolfert VI was later to use the original family weapon on his coat of arms after the death of his father, Hendrik II. And the third reason is that no insignia are present in the decorated margin around the coat of arms of the Order of the Golden Fleece. Wolfert VI became a knight of the Golden Fleece in 1478 (Wijsman 2010, 263 n. 27).

Author

Mirelle Peeters-Nunes, September 2014 (edited version, July 2020)