'Natuurlyke historie' by Renard

Neither fish nor flesh

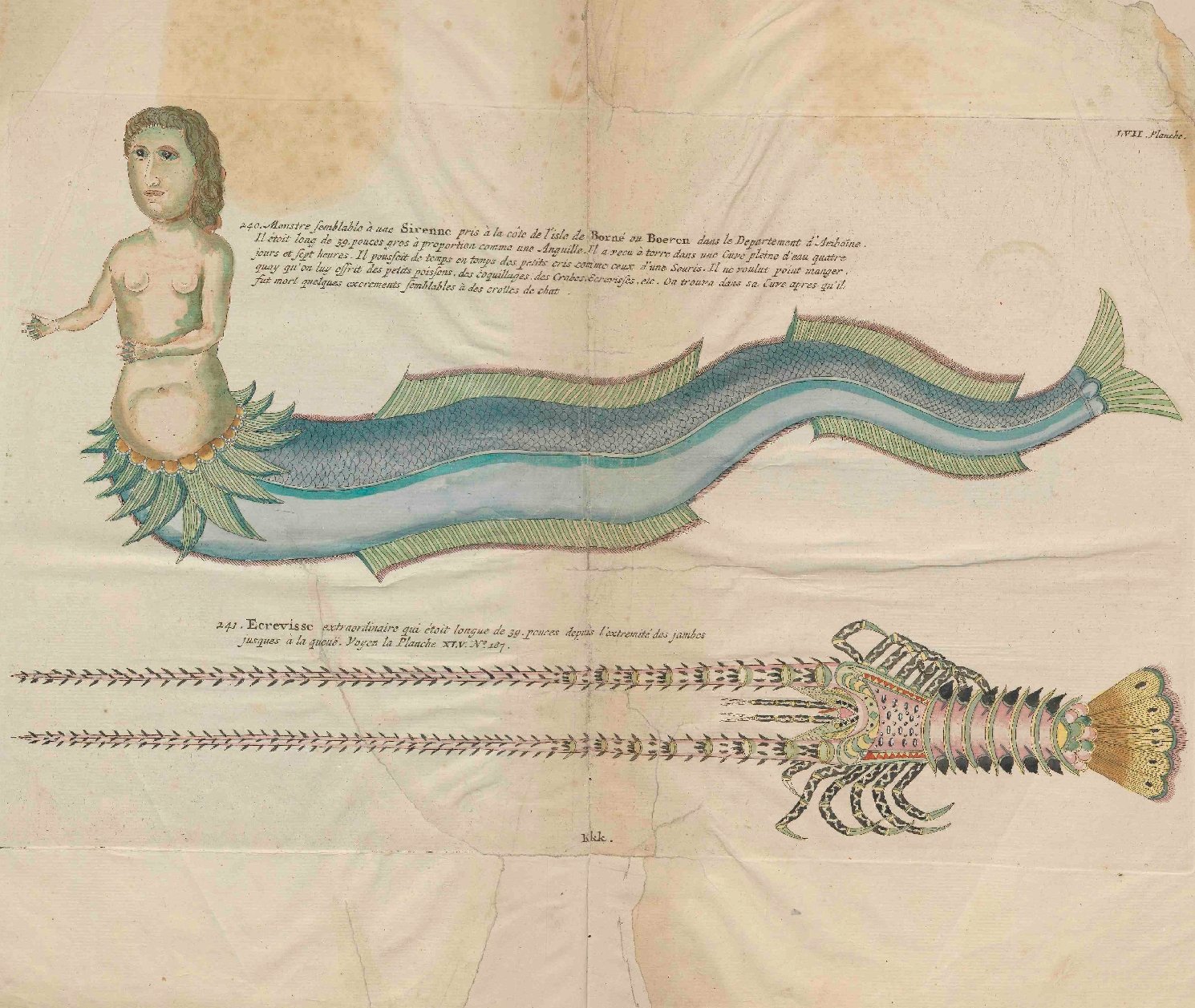

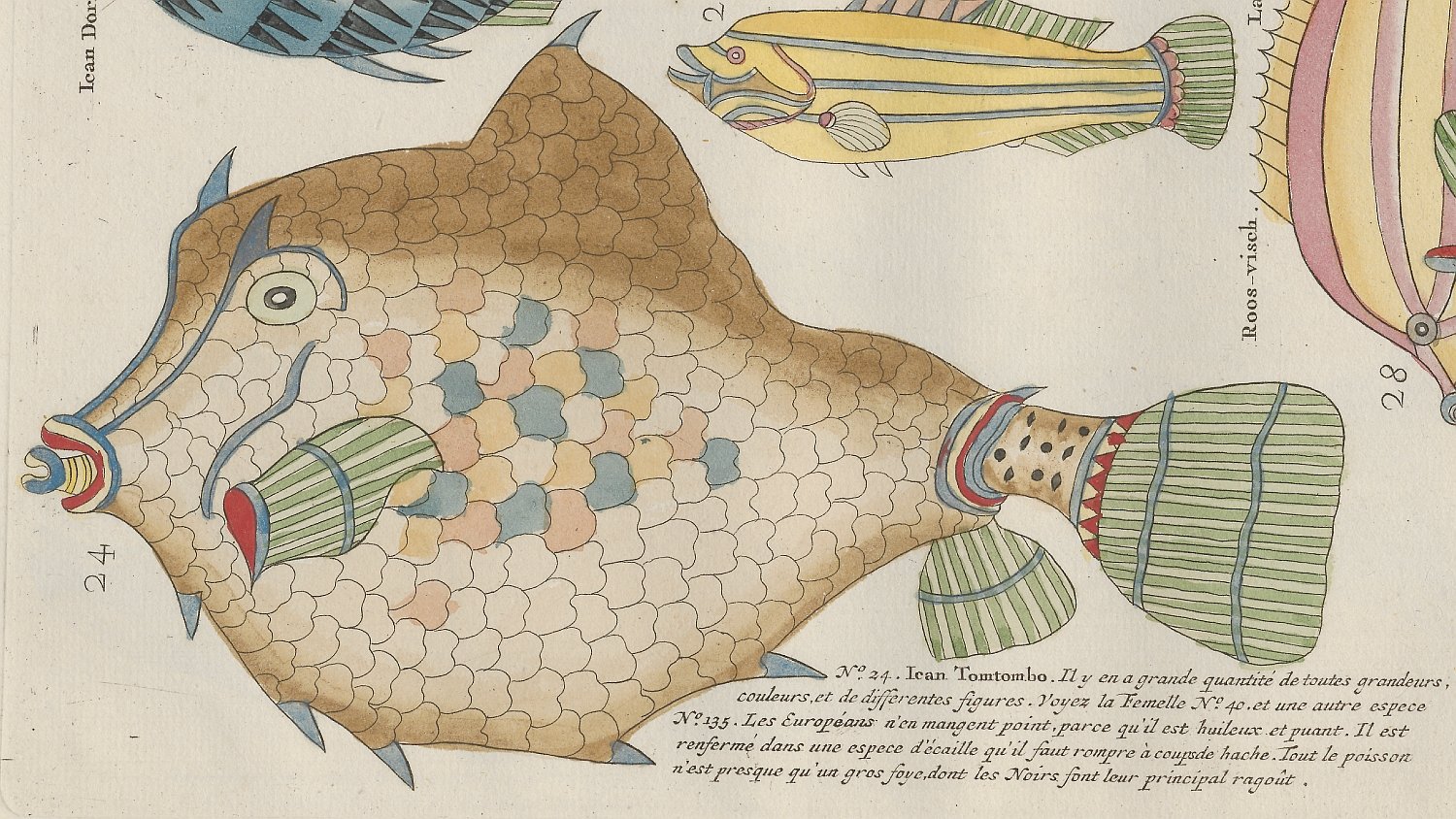

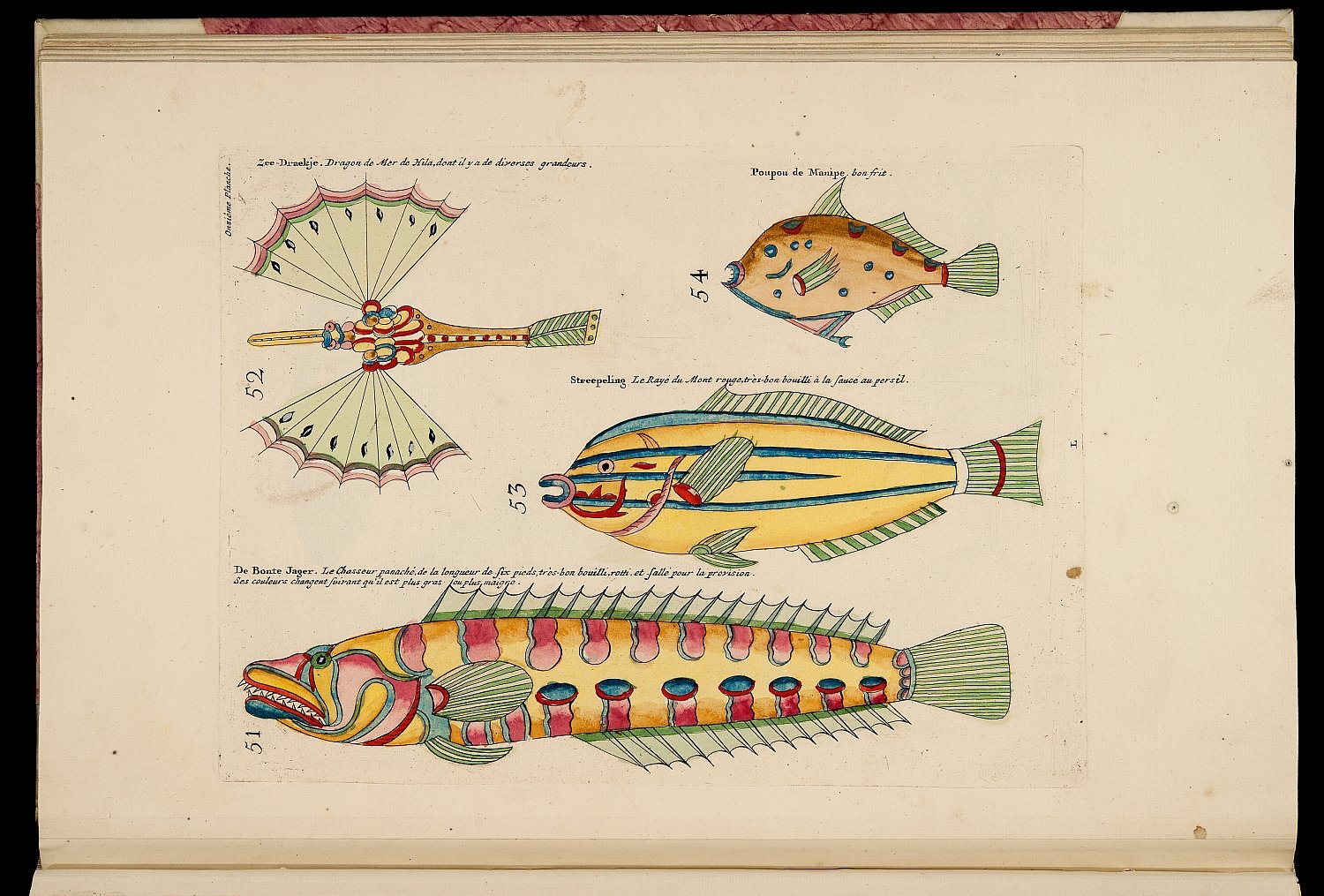

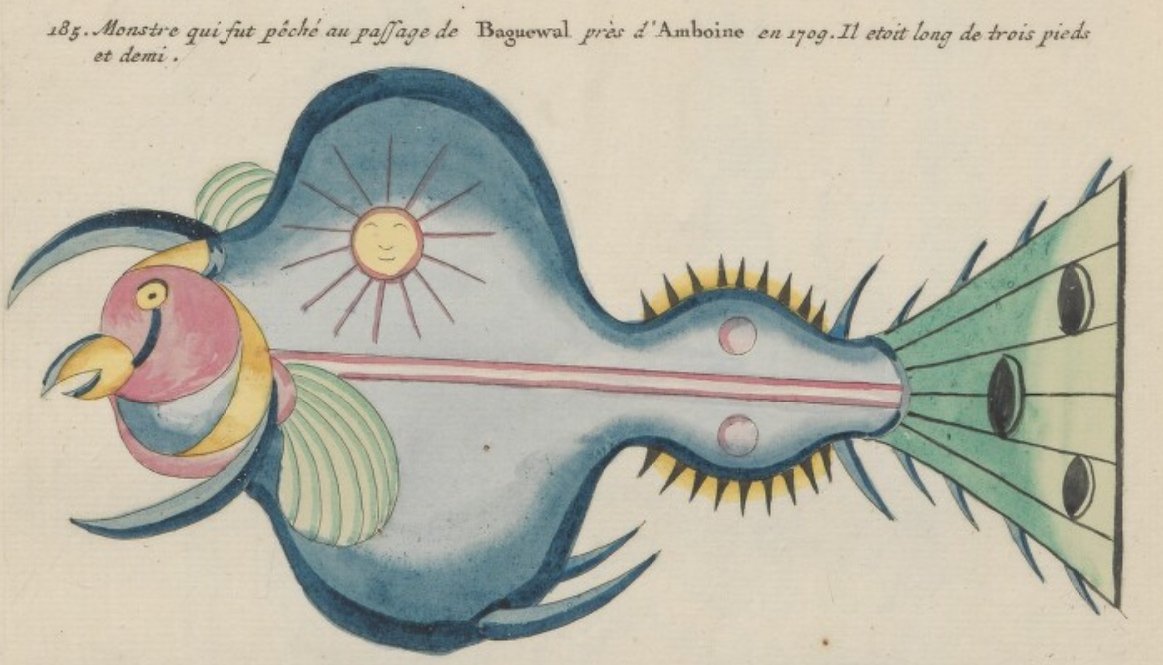

A motley collection of spectacular pictures of hundreds of fishes, crustaceans, stick-insects and even a true mermaid. The Amsterdam bookseller and publisher Louis Renard (1678/79-1746) included them from 1719 onwards in his zoological publication Poissons, Ecrevisses et Crabes […], better known under the half-title Histoire Naturelle or Natuurlyke Historie. At first sight these surrealistic sea creatures, which were supposed to live in the East-Indian waters, seem all to have originated from an imaginative mind, but is that really true? A visit to the colourful and miraculous world of Renard’s Natuurlyke historie via the rare third edition from 1782 will provide us with an answer.

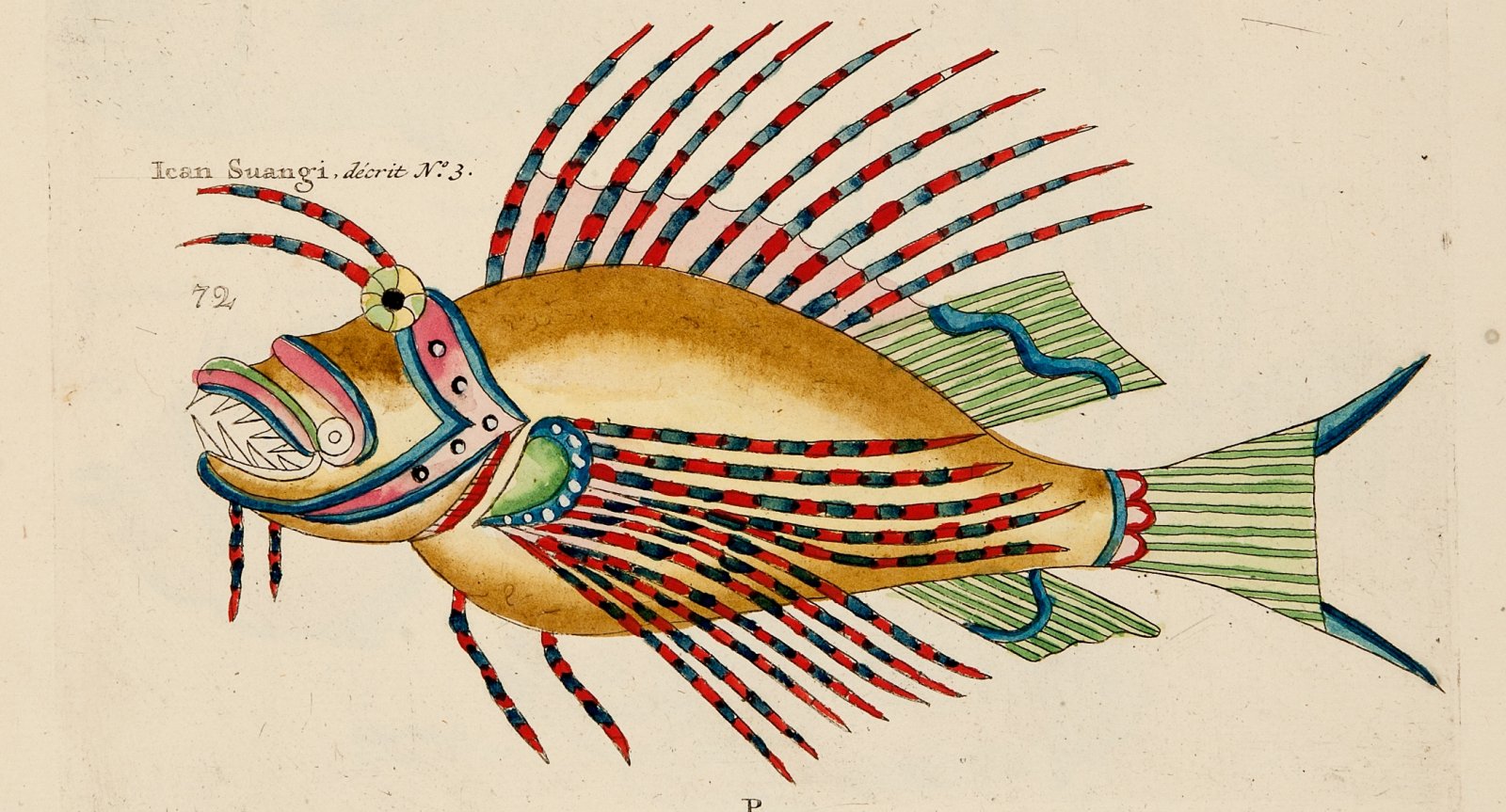

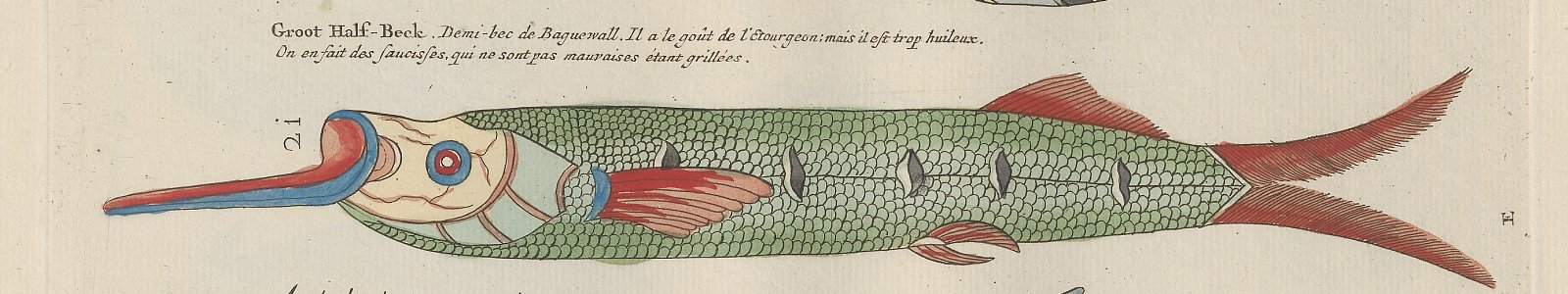

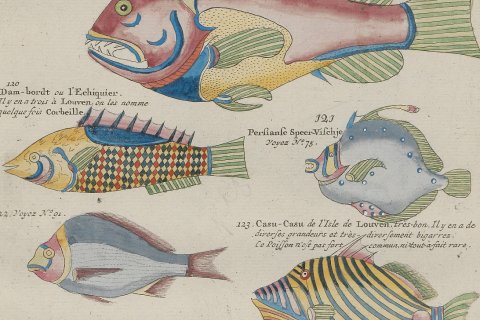

Initially Renard’s Natuurlyke Historie must have been considered as a scientific standard work. However, this reputation did not last long and the work was practically ignored by 19th and 20th-century biologists and zoologists. It is true that they valued the work in an aesthetic and cultural-historical sense, but from a scientific point of view they criticized its many shortcomings. This is no wonder: most sea creatures are depicted in an exaggerated way and contain many unrealistic embellishments. For instance, on the scales of some fishes we see little hearts, stars, suns and moons. The fishes are even adorned with pictures of potted plants while within the head of a sea louse a small human face can be recognized.

Copies of copies of copies

The given colours of the fishes are quite arbitrary too. Artist Samuel Fallours, employed by the Dutch East Indian Company, made several sets of drawings by duplicating them. For his illustrations he relied on existing collections of manuscript drawings which in their turn were also copied. The drawings in the first part were based on the collection of Balthasar Coyett, former governor and ambassador of Ambon and Banda. The illustrations in the second part were copied from the collection of Adriaen van der Stel, governor of the Moluccas. Copying copies meant an increasing chance for mistakes. In addition, Fallours probably tried to reconstruct partly decomposed fishes. As a result some specimen appear to exist of two species of fishes. The history and genesis of Renard's remarkable publication is thoroughly researched by Pietsch (1993 and 1995). He also suspects that Fallours in this way had more chance of selling the more spectacular pictures in Europe.

Edible fishes

Apart from the pictures in the Natuurlyke Historie the accompanying descriptions are anything but accurate. What’s more, many descriptions are anecdotal with a high entertainment value. Several fishes are judged by their edibility and of some fishes a recipe is given. Of the ‘Ican Tomtombo’ or thornback boxfishes (part II, no. ) is said that it cannot be eaten by Europeans because of its oily taste and awful smell. On the other hand, the indigenous people are said to make a stew out of it…

Strange creatures in Fallours’ home

Apart from the edible character of the fishes, Fallours mentions other eyebrow-raising facts. In the description of the Sambia or frogfishes (part III, no. 330) he claims: ‘I kept the animal for three days in my house: it followed me everywhere, just like a small dog.” And at the mermaid mentioned before (part II, no.241) is written that she was caught on the isle of Boeroe or Buru near Ambon. In Fallours’ house the mermaid had lived for four days, and seven hours in a container of water. With regular intervals she squeaked like a mouse. Finally she died of starvation because she refused to eat.

Utrecht involvement with the third edition

In 1782 this third ‘edition’was published at the Utrecht publisher Abraham van Paddenburg and the Amsterdam publisher Willem Holtrop. Pietsch only mentions six well-known copies, including the one held by Utrecht University Library. He thinks the third edition is so rare because the publication was never finished. Compared to the first and second editions the preliminary pages of the third edition have been replaced by short synonyms in the Dutch and French language and descriptions spread over two columns, written by the Dutch doctor and natural historian Pieter Boddaert (1733-1795). Boddaert’s texts, however, only refer to the depicted fishes and crustaceans in the first part. Nonetheless most of the surviving copies of the third edition contain prints of all hundred copperplates which were used to create his book and so shows all available picture of East Indian sealife.

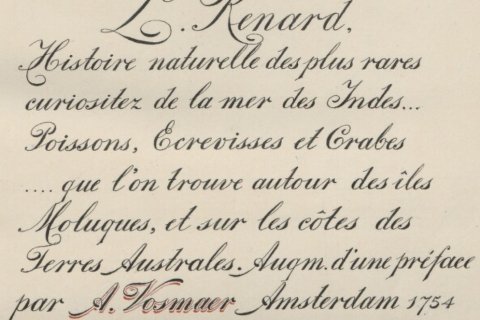

Handwritten title page

Only in 1985 it was discovered that this copy concerns the rare 1782 edition; before that it was incorrectly thought to be the 1754 edition. This is not as strange as it seems, because the Utrecht copy starts with a handwritten title page which seems to be a direct copy of the title page of the second edition and is dated accordingly. Who is responsible for this title page will forever remain a mystery. Anyway, the book came into the possession of Utrecht University Library via the collection of the National Veterinary School, founded in 1821. In 1925 the school became part of Utrecht University.

Exact science?

In the days that Natuurlyke Historie was published, hardly any scientific knowledge was available about marine life in the East-Indian islands. One had to make do with a few scattered entries in general botanical works by for instance Clusius (1605), Boutius (1658), Nieuhof (1682) and Cornelis De Bruin (1714). Renard wanted to set this lack of information right and in his Natuurlyke Historie pretended to offer one of the first systematic overviews of East-Indian fishes. In this way the publication is a product of the Enlightenment era with its pursuit of exact science. But to what extent can the Natuurlyke Historie be called exact? Including a mermaid can hardly be labelled scientific, now can it?

Drawings by Fallours

In the 18th century three editions were published of Renard’s book, all three containing the same pictures: a total of460 engraved illustrations, printed from a hundred copperplates, 415 fishes, 41 crustaceans, two stick-insects, one Indian dugong and one mermaid. They represent tropical kinds from the East Indies which, according to the text, have been drawn to life on the isle of Ambon in the South Moluccas by Samuel Fallours.Renard, who as far as we know never travelled abroad, acquired the original drawings from several persons. These people transported the drawings to Holland in 1708 and 1715.

First edition at Renard

A hundred copies of the first edition in the French language of the Natuurlyke Historie were printed in 1719 at Renard’s. Only fourteen are still known today. The copy held by the Warnock Library has been digitised and is available online. The first edition consists, just as the other editions by the way, of two parts and includes a dedication to King George I of England - Renard also acted as an agent for the British crown - and an advertisement in which the authenticity of its contents is emphasized.

Second edition at Ottens

In 1754 the Amsterdam publishers Reinier and Josua Ottens published the second edition of the Natuurlyke Historie, also in French. Probably again a hundred copies were planned, the existence of 33 copies has been established. Compared to the first edition, the title page was slightly edited and an extensive foreword was added, written by Arnout Vosmaer, a collector of naturalia (1720-1799), and an introduction by Renard written as early as 1719. The still remaining copies of the second edition show a rather varied order in their contents. This may be because the Ottens firm not only acquired the old copperplates from the estate of Renard (and used them for new prints) but also 30 or 36 sets of still unbound and non-coloured prints of the first edition. The second edition was sold for fifty guilders a piece. Also in those days one had to pay for one’s fish!

Reality over fantasy

In view of the numerous fantasies and shortcomings it is not so strange that Renard’s Natuurlyke Historie has not had a great scientific influence on the development of marine zoology. None of the 460 illustrations give an accurate representation of living sea animals. Yet Pietsch shows that, apart from the wrong colouring and anatomical flaws, the majority of the pictures bears a relation to existing sea creatures. Based on colour patterns, certain characteristics of the species and ‘some zoological intuition’ sixty percent can be reduced to species, over twenty percent to a certain genus and ten percent to a certain family. So less than ten percent is based on pure fantasy.

Scientific?

All in all Renard’s Natuurlyke Historie cannot be dismissed as an unscientific publication. There is scientific content, in which the figures are indeed overdone and sometimes unrecognizable, but still largely based on natural objects. In addition it is one of the rarest works in the field of natural history and the earliest known work with coloured depictions of fishes. But it must be said, sometimes very peculiar coloured and shaped fishes…

Author