'Sinnepoppen' by Willem Jansz. Blaeu

Wise lessons about the pursuit of wealth

Sinnepoppen (1614) by Roemer Visscher (1547-1620), a merchant from Amsterdam, was probably the most popular emblem book written in the Dutch Golden Age. Simply put, emblem books are compositions of cryptic text (motti and subscriptios) and images (picturae). This literary genre was introduced in 1531 when the publisher of a volume of Latin epigrams by the Italian Alciato decided to illustrate his poems. The concept soon gained popularity among scholars and several editions of Alciato’s Emblematum liber were printed in Europe. It did not take long before new emblem books followed, which were not solely directed at scholars, but were also written more simply or in vernacular for a wider audience.

Money and profit

Emblem books on love were particularly popular in the Low Countries. They included provocative text and imagery that was intended to teach the reader in a playful manner about subjects such as love, heartbreak, marital fidelity and choice of partner. The practical impact of emblem books on love reached its height when Jacob Cats published Sinne- en minnebeelden in 1618. The emblem book Sinnepoppen by Visscher is not about love, however, conveying instead a moral lesson about money and profit.

Roemer Visscher, businessman and member of the cultural elite

In the first two decades of the 17th century, Visschers house on Geldersekade served as a meeting point for the cultural elite of Amsterdam. As successful businessman, he accumulated a fortune and was also well-read in Latin, Italian and French literature, affording him the opportunity to raise his famous daughters Anna and Maria Tesselschade with an appreciation of art. He was also the leading member of the In liefde bloeiende chamber of rhetoric.

Emblem books

Visschers strength proved to be short poems, including emblems. In Leiden in 1612, some of Visschers poems were printed without his knowledge. He responded to this with the emblem book Sinnepoppen in 1614. Published by the well-known publisher Willem Jansz. Blaeu of Amsterdam, the work included 183 emblems, divided into three sections or schocken in Dutch, which refers to the sixty emblems in each section of the book. The images are etches touched up using a burin, which were created by the illustrator and publisher Claes Jansz. Visscher, who – incidentally – was no relation to Roemer.

‘A short, sharp discourse’ that everyone can understand

Roemer Visscher was a self-confident advocate of literature written in vernacular. The preface to his emblem book describes emblems, or sinnepops as he called them, as a short, sharp discourse that everyone can understand. The preface reads as follows, 'Sinnepop dan is een korte scherpe reden, die van Ian alleman, soo met het eerste aensien niet verstaen kan worden: maer even wel niet soo duyster datmer nae raden, jae of nae slaen moet: dan eyscht eenighe na bedencken ende overlegginghe, om alsoo de soetheydt van de kerle [= kern] of pit te smaecken.'

Not too difficult, not too simple

To put it simply, an emblem should be neither too difficult, nor too simple. Visschers emblem ‘Licht en dicht’ (first section, XXXVI, p.35) is a good example of this: 'De glasen vensters in Kercken en Huysen zijn licht, laten de lucht ende de sonne deur hen schynen, en zijn dicht voor de vvindt, die zy buyten keeren. Dit en behoeft gheen vorder uytlegginghe, dan een yeder mach het ghebruycken daer’t hem te passe komt.'

Compliments on business sense

In a break with the tradition of the time, the prints in Sinnepoppen were not accompanied by verses, but by prose in conversational tone. The book displayed a range of typically Dutch objects, including ships, locks, skaters, mills and tulips, as well as many tools and instruments, such as a compass and a saw. While a stand was taken against the pursuit of wealth and extravagance, the Dutch were complimented on their business sense and creativity.

Gap in the market

With new editions printed in 1620, 1669 and 1678, it became clear that Sinnepoppen filled a gap in the market. For these editions, Visscher’s daughter Anna added a range of moral verses to the original. She also included ten new emblems and altered some of the prose commentary and the order of the emblems.

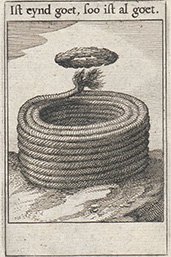

In conclusion, the dignified final words of ‘Ist eynd goet/soo ist al goet’ from Visscher’s Sinnepoppen (first section, LX, p.60): 'Alle dinghen worden begonnen, om die met kosten, arbeyt ende neerstigheydt te brengen tot het eynde; soo dat dan soo goet is, dattet den aenleggher vernoeght, soo heeftet den krans of prijs verdient, ende men moet het prysen. Dit vverdt uytghebeeldt met een tou of cabel die men aen’t eynd besiet, en beproeft of de stoffe goet is. En soo seytmen: Ist eynd goet, soo ist al goet.'