The description of England by Abraham Booth

A seventeenth-century travel guide: the description of England by Abraham Booth

Today, anyone who wishes to travel abroad need only look for their destination online, or simply pick up a guidebook at the bookshop. Questions about the history, laws, or customs of other countries can generally be answered with a quick search on the internet or a short trip to the library. These options were clearly not available to the early modern reader. Perhaps Abraham Booth, secretary of the Dutch East Indian Company (VOC), intended to provide such information when he penned his Description of England, or Englandts Descriptie, in 1630.

Writing the Descriptie

Booth travelled to England in 1629 as secretary to the Dutch delegation sent to negotiate the release of three captured merchant vessels. These ships had been seized by the English to speed up negotiations surrounding the infamous Amboyna Massacre of 1623. While in London Booth kept a personal journal, which survives in two parts and is discussed in more detail here. After his return, but perhaps already during his stay in London, Booth worked on the text that was to become Englandts Descriptie. This book is longer than his journal and consists of several sections marked by separate title pages. It contains, among other things, a brief history of the kings and queens of England, lengthy tracts on English law and government, several suggestions for trips around the countryside, and descriptions of the various towns and grand houses that dot the landscape. It appears to be a remarkably thorough work, and compiling it would no doubt have been quite an undertaking.

English history and law

Booth starts the Descriptie with a concise listing of the kings and queens of England. Each ruler is given just one short paragraph in which their entire reign is summarized, although some receive a bit more attention than others. Surprisingly, the more recent monarchs are discussed more briefly than the earlier ones. It may be that the legends surrounding these had yet to grow and cloud the facts, but it may also just have been considered untoward to scrutinize a recent monarch’s reign. Booth’s sources mostly go unnamed. He likely used books that he found in England combined with whatever information his English acquaintances and family could provide him with. Other aspects of history are not really touched upon in this section, but local history is often discussed during his later treatment of towns and cities.

Booth also seems to have taken a particular interest in English law, given how much space he reserved for it in his book. He introduces various legal matters, such as inheritance laws and the rights of women – which, perhaps unsurprisingly, are rather lacklustre for modern standards, as can be seen on fol. 33v, where Booth states that ‘the woman has no possessions of her own’. The section is lengthy, but its appeal is limited to a modern reader who is not interested in early modern English law codes.

Following this is the section that bears the most resemblance to a modern-day travel guide, and is where the Descriptie really begins to come alive. Here Booth introduces notable English cities and towns, giving information on local history, sometimes explaining the meaning behind their names, and listing the major sights and unique selling points of each location. To top it all off, he groups them together in handy itineraries that can be undertaken from London over a period of several days, also listing smaller stop-over villages in between, where a weary traveller and their horse could rest and enjoy a quick repast. Although these descriptions look like an instructional guide for other would-be travellers, this is likely not what Booth intended them for. They may just as well have served as mementos of the trips he made himself, purely for personal remembrance rather than for the benefit of the public.

Next, Booth turns his attention to descriptions of several English cities and towns. Although he included an exhaustive list of all the English counties at the start of his description, this section mostly deals with those places he visited himself on his many outings. How much Booth writes about a town seems mostly related to its standing, but is perhaps also decided by his personal interests. Oxford and its university receive the most attention, aside from London. Interestingly, when discussing Oxford’s status, Booth also revisits Matthew Paris’ (1200-1259) claim that Oxford University is the second of the four most prominent universities. The fact that Matthew Paris had died almost three-and-a-half centuries before Booth was even born did not seem to matter much to him.

The unique features Booth discusses for each town are not all equally riveting. Colchester’s biggest claim to fame, according to Booth, seems to be its extraordinarily tasty oysters, which were renowned across Europe and were even known in the time of the Roman author Pliny the Elder. Norwich, meanwhile, boasted a bowling track of over 80 steps. A sport in which, Booth adds, ‘the English take a remarkable delight’ (fol. 113r). While Colchester is still known for its oyster today, other things change over time. Bristol was seen as England’s third city, according to Booth, and Norwich its second most important. He even adds that many claim Norwich takes up as much land as London does, although it is not as crowded as the capital. Not entirely out of the realm of possibilities when comparing it to the historic centre of the City of London, but still an outlandish thought today.

Some of Booth’s comments become remarkably poignant with the benefit of hindsight. In Northampton, for example, he mentions that the city is large but also feels run down. In truth, Northampton had served as a royal residence for decades, and was a rich and powerful city throughout the middle ages. The Black Death, however, claimed the lives of many of its inhabitants, and it would never fully recover after that. In fact, he could consider the timing of his visit rather fortuitous. Had he come to Northampton just eight years later he would have found it ravaged anew by the Plague.

The Descriptie as a source

Included in his descriptions of towns are little nuggets of etymological information. For some of the more sizeable places Booth explains the origin of their names. Quite a few of these etymological explanations are interesting to read, but can be grossly inaccurate. Whether the correct origin of a place name was simply not yet known at the time, or whether Booth was misinformed is often difficult to tell – something that goes for the rest of the facts presented in the book as well. For Oxford, Booth claims its name was derived from it being a ford in the river Ouse, a theory that dates back at least to the time of famed English antiquarian John Leland (1503-1552). In truth, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, the name actually derives from Old English Oxnaford, or ‘ford of oxen’. While no longer reliable for the modern reader, Booth’s lessons do reveal that people had already taken an interest in the origin of their towns.

Booth’s personal loyalties do surface from time to time in his otherwise mostly objective description. He mentions, for example, that a large number of Dutchmen reside in Norwich. In fact, he seems most complimentary of Yarmouth of all English towns, largely because it possesses ‘the largest similarity in buildings and neatness of the streets to our Dutch cities of any place in England’ (ende de grootste gelijckheyt in gebouw ende netticheyt van straten met onse Nederlandtsche steden van eenige plaetse in Engellandt, fol. 120v). Apparently, being similar to Dutch towns is the greatest honour an English town can strive after! He proudly adds that a lot of Dutch fishermen live there, who attend a specially built Dutch church. As it turns out, that very church had a congregation of a whopping 28 male members in 1635 (Grell 1989, 84).

Booth also records many humorous rhymes about England, or the English. Given that they are in Dutch and are not exactly flattering, it is possible that he learned these from his fellow countrymen rather than hearing about them in England and translating them into Dutch himself. Two of these, while informative on their own, present something of a paradox when combined: ‘England is like hell to horses, purgatory to servants, and heaven to women’ (fol. 5v), and ‘England’s beauty: men at the gallows, women in the brothel’ (fol. 31v).

Booth as a critic

While the Descriptie is already worth a read for its factual content, it is at its best wherever Booth was tempted to include his opinion on the things he saw. While describing St Albans Cathedral he quotes a Latin verse found on its walls, which he claims he chose to add ‘because of the ridiculous manner of making verses in that age’ (om de belachelijke maniere van veersen te maecken in die euwe). The verse reads M.S. Vic Domini verus iacet his Eremita Rogerus et sub eo clarus meritis Eremita Sigarus (fol. 118r-118v). Booth was clearly not impressed by the lazy rhyme in the names ‘Rogerus’ and ‘Sigarus’.

Early modern Street View

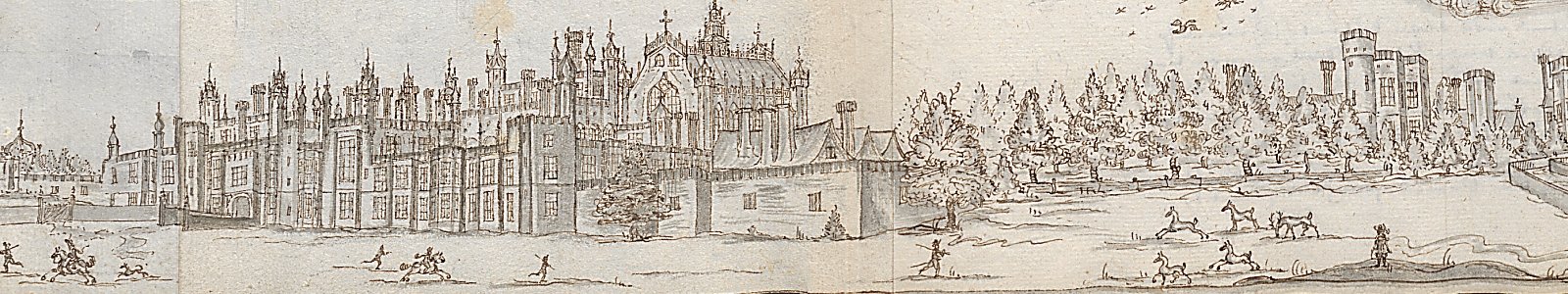

While Booth’s writing contains a treasure trove of information, the Descriptie’s biggest claim to fame originates elsewhere. Included between fol. 82 and 84 of the manuscript was an engraving entitled ‘The view of the cittye of London from the North towards the Sowth’. It showcased the entire south side of the city, seen from the northern banks of the Thames. While panoramic images of London are relatively bountiful, this particular engraving is unique in that the overwhelming majority instead shows the city the other way around, from the north to the south. Adding to its value, the engraving found in the Descriptie was for a long time the only known surviving copy. A second copy surfaced in the summer of 1996, when father and son Clive and Philip Burden, both antiquarians, found it hidden inside of a different book already purchased in the early 1970s, an early edition of John Speed’s Theatre of the Empire of Great Britain. This copy remains in the possession of the family. The Utrecht engraving was removed from the Descriptie in August 1985 to be restored, and has since been kept separately (Gr. Form. 12).

Dating the View

Where would Booth have acquired this picture? As with the other engravings featured in his Descriptie, he probably purchased it from one of the various vendors he encountered during his travels around the country, much like how a tourist today takes pictures or collects picture postcards of the most impressive sights. There is no significant evidence pointing to a specific seller or even artist. Researchers have spent a lot of time on dating the vista on the engraving, with estimates ranging from between the final years of the 16th century to 1620 at latest. A commonly held view today is that the scene is from around 1597 (Lusardi 1993, 227).

Shakespearean cameo

This plausible answer was found by studying some of the more noteworthy structures in the cityscape: the theatres. Two are clearly visible, with the first being located on the far left of the engraving, a hexagonal building flying a flag, with the second slightly towards the right. Which theatres these are actually meant to portray was, and still appears to be, hotly debated, but there is no doubt that at least one has a strong connection to England’s bard, Shakespeare. The theatre most often associated with him is the Globe, which was built in 1599 by his playing company, The Lord Chamberlain’s Men. It was constructed by reusing the timber left over from an earlier theatre, imaginatively called ‘The Theatre’. Some speculate that this is the leftmost theatre featured in the engraving, the one to the right being the Curtain, but the jury is still out on this one (Lusardi 1993, 227).

Fit for publication?

More so than his journals, Booth’s Descriptie of England feels like a fully-fledged work that could have been published. It covers a variety of topics, all related to England, and none of it is as personal or inappropriate for printing as his own journals were. It is also presented in a fairly orderly and accessible way, with the text being clearly divided over several sections, chapters, and paragraphs. Some of the different sections even have neatly drawn title pages. Even so, this is no guarantee that he ever meant for it to be made public. Today, still, people put effort into gathering pictures to create the perfect photo album, or work on their scrapbooks, without the intention of publishing them. But the large amount of purely practical information he included – especially the long section on English law – seems a bit much if it had just been intended to serve as a memento. While we may never find out what Booth had planned to do with his book, we can at the same time still appreciate it for what it is now.

Survival of Englandts Descriptie

We have Abraham’s illustrious family to thank for the survival of his works: his brother, Cornelis Booth, became the first librarian for the newly formed Utrecht University Library. After Abraham’s untimely death at the age of 30, his papers were held by Cornelis, whose heirs did not start selling his affairs until nearly 200 years later. They eventually made their way to the Utrecht Provincial Archives, after which they were transferred to the University Library in 1882. It is not unlikely that, without his brother’s social standing and line of work, Abraham’s insightful writings and the essential engraving of London would never have survived to this day.

Booth’s work and legacy

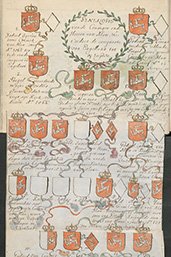

Aside from the Descriptie, Booth also wrote a private journal in two parts during his time in England, as well as a public one for the embassy to Sweden and Poland, which was published in 1632 (Journael vande legatie …). One other manuscript by his hand remains in Utrecht: T’ Hof van Vrankryck (The Court of France, Ms. 1321). Written in 1624 at the tender age of sixteen, it predictably contains a description of the court to the king of France, including all the notable figures that frequent it. Like the Descriptie, the Hof includes some coloured drawings of coats of arms and extensive information on the aristocracy, which has led to Booth being called ‘a good genealogist and an outstanding illustrator of coats of arms’ in part four of the Nieuw Nederlandsch Bibliografisch Woordenboek (New Dutch Bibliographical Dictionary), published in 1918 (vol. 4, 215). Considering his brother’s interest in genealogy it is not unlikely that the younger Booth also possessed some knowledge on the subject. While the Hof is not directly comparable to the Descriptie, due mostly to its much narrower scope, it still shows that even at a young age Booth was interested in compiling descriptions of other countries. We can only guess what else he would have produced had he lived to a ripe old age.

Author

Nick Becker, July 2015