Heidelberg Catechism 1563

Unique copies of the Heidelberg Catechism

The Heidelberg Catechism from 1563 is one of the most influential and widely read books in Protestantism. It has been translated into dozens of languages and has been the basis of religious instruction in churches, schools and at home. However, the first editions of the work have become very rare. Utrecht University Library owns the most copies of the first editions of 1563 in the world. The story of their origin is a remarkable tale of coincidence, detective work and wealthy friends.

The Lord’s Supper as point of dispute

When Martin Luther, the most important initiator and leader of the German Reformation, died in 1546, several German cities and principalities had embraced Protestantism, often much opposed by the Catholic German emperor. But there was also discord among the Protestants themselves, for instance about the question of the importance of the Lord’s Supper and the role that bread and wine played in this rite. According to the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation, bread and wine are actually changed into the body and blood of Christ at mass. Among Protestant theologians opinions varied from a purely symbolical act (Zwingli) to an act in which Christ and His grace are received, without Christ being actually present (Calvin) or, on the contrary, with Christ being present (Luther).

The doctrine formulated

Frederick III, Elector Palatine, inclined more and more towards Calvin’s reformed opinion, a thorn in the flesh of the Lutherans. To formulate a well-defined doctrine for the Palatinate, he invited several theologians to Heidelberg in 1560 and 1561. Zacharias Ursinus, one of Calvin’s pupils, was put in charge.

The composition of the Heidelberg Catechism

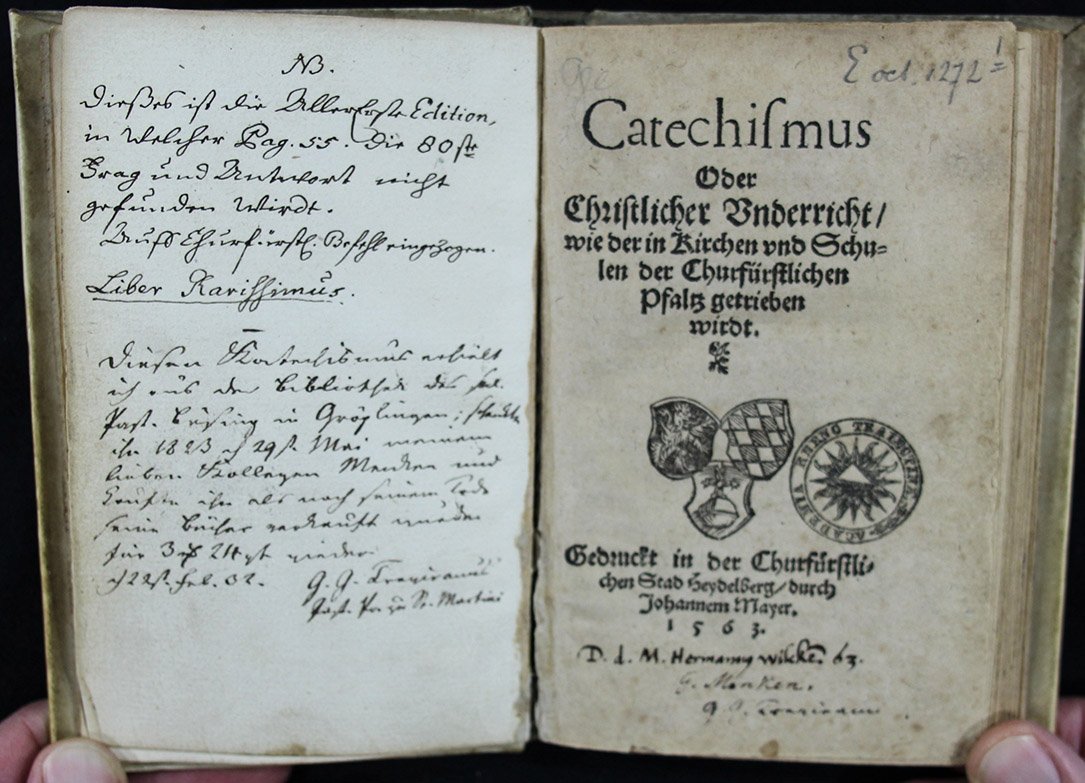

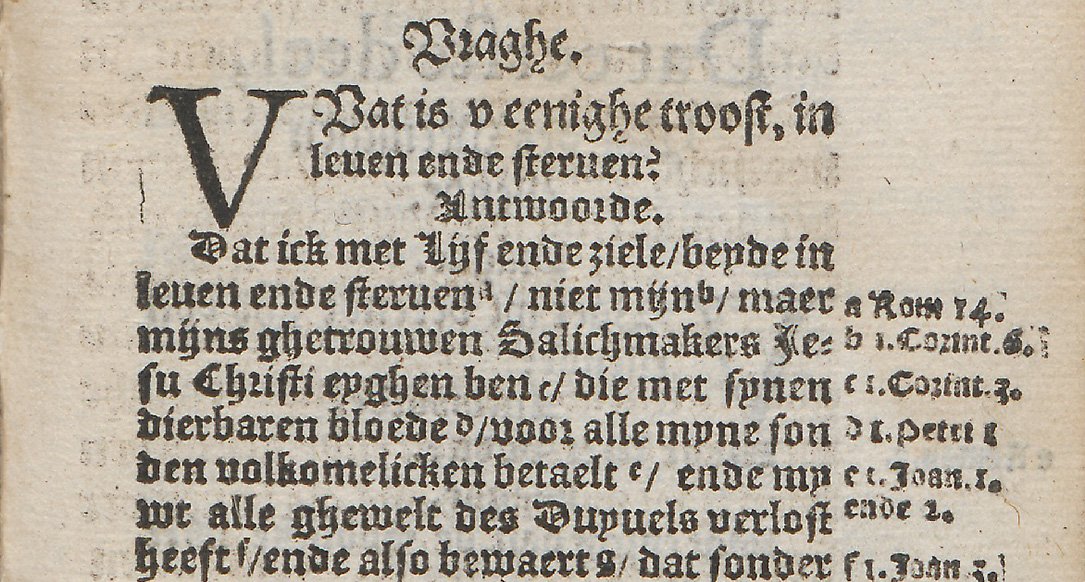

Ursinus used several Protestant catechisms already in circulation, and presented the catechism for the Palatinate to Frederick III and the Heidelberg ministers and university theologians in January 1563. After approval and an introduction by Frederick himself the first edition was published about a month later under the title Catechismus oder christlicher Underricht, wie der in Kirchen und Schulen der Churfürstlichen Pfaltz getrieben wirdt. It consists of 128 questions and answers in High German about the Protestant doctrine. The answers are usually derived from the Bible, for instance question 36: ‘Frag: Wass nutz bekomestu auss der heiligen empfengnuss Christi? Antwort: Dass er mit seiner unschuldt und volkommenen heiligkeit meine sünde, darin ich bin empfangen, für Gottes angesicht bedecket (Ps. 32, I Cor I)’ (p. 30).

Additions

Besides the questions and answers three sections were added: I. Summa des göttlichen Gesetzes; II. Die Artickel unseres christlichen Glaubens; III. Das Gesetz oder die zehn Gebot Gottes, finishing with Das christliche Gebet (Unser Vater). They are followed by a separate text with its own title page, but which is an inseparable part of the earliest edition of the Heidelberg Catechism, the Christliche Gebet, die man daheim in Heusern, und in der Kirchen brauchen mag. However, this text is hardly discussed in the specialist literature.

The second edition and question 80

At the request of Frederick III a question about the Lord’s Supper was added as the 80th question and answer to the second edition: ‘Was ist für ein Underschied zwischen dem Abendmal des Herrn, und der bäpstlichen Mess?' There are also some other adjustments. The second edition appeared in April 1563. The three sections and the Christliche Gebet remained a fixed part of the Heidelberg Catechism. However, there is an edition of the Christliche Gebet with slightly different quire numerals than those of the first two editions of the Heidelberg Catechism (E oct 1281, pt. 3), but if we are dealing with a special edition here is not sure.

The ‘final’ third edition

In the third edition the answer to question 80 was extended and the Christliche Gebet was removed (facsimile: Zürich 1983). At the end of 1563 the third edition was added to the collection of texts Kirchenordnung, wie es mit der christlichen Lehre, heiligen Sacramenten, und Ceremonien, inn de durchleuchtigsten Herrn Friderichs Pfaltzgraven bey Rhein … gehalten wird. In the next few years the third edition was often published separately, and so became the starting point for all following prints, editions and translations. Also the 129 questions and answers were divided into 52 parts, so that each Sunday in the year two or three questions could be dealt with in church or religious teaching. This was already common practice in other catechisms.

The Dutch translations of 1563

In 1563 the Heidelberg Catechism was translated and printed into three languages: in Dutch (Nederduytsche Spraeke), in Saxon (Sessische Sprake), and in Latin. The Dutch translation is the oldest. It was printed in Emden in 1563 based on the second High German edition. In the same year another Dutch translation was printed in Heidelberg, based on the third edition. Peter Datheen was the translator, even though he is not mentioned as such. In 1566 a slightly adjusted version of Datheen’s translation was published, preceded by the first edition of Datheen’s rhymed version of the psalms. Again Michiel Schirat was the printer in Heidelberg. This was the same year in which the first Protestant field preachings were organised in the Netherlands, and the Iconoclastic Fury (Beeldenstorm) took place.

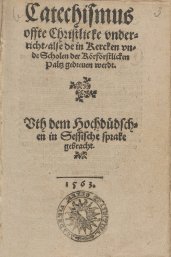

Other translations

The Low Saxon (Low German) translation was meant for the northern part of Germany, and was titled Catechismus offte Christlicke Underricht, alse de in Kercken unde Scholen der Körförstlicken Paltz gedreven werdt, uth dem Hochdüdschen in Sessische Sprake gebracht. It is based on the third High German edition, as is immediately made clear from the extended answer to question 80. Yet the Christlicke Bede, de man tho Huse unde in der Kercke brucken mach is still added. The translator of the texts is M.J.L., probably Magister Jozua Lagus. Together with Lambertus Ludolphus Pithoppeus he also edited the Latin translation (1563), also based on the third edition. Here, too, the Catechesis religionis Christianae, quae traditur in ecclesiis et scholis Palatinatus is followed by the Precationes aliquot privatae et publica. After 1563 other translations saw the light of day, such as those in English (1572), Hungarian (1577) and French (1590) – the latter produced in Haarlem for the French Huguenots in the Netherlands. The Heidelberg Catechism was accepted as a confession of faith at synods. For centuries it formed the basis of religious teaching and instruction for a large part of Protestant Christianity.

The Utrecht copies

We have to thank Jacobus Isaac Doedes (1817-1897) for the fact that Utrecht University Library houses the largest collection of Heidelberg catechisms of 1563 in the world. Doedes was professor of Theology in Utrecht and worked on a history of the Heidelberg Catechism which he completed in 1867.

The first three High German editions

Utrecht University Library owns two copies of the first High German edition of the Heidelberg Catechism (E oct 1272 rar en E oct 1272* rar), of which only a few other copies exist (e.g. Kiel, Zentralbibliothek, Arch4 332). There is also a copy of the second High German edition (F oct 266 rar) and one of the third edition (E oct 1272-a rar). There is an early copy of the edition of the Kirchordnung from 1565 (F oct 68 rar), in which the questions and answers are divided into 52 Sundays. F oct 68 rar comes from the collection of Huybert van Buchell (1513-1599). F oct 266 rar was donated to Utrecht University Library by Maria Jacoba Meinertzhagen, the widow of the Utrecht magistrate Cornelis Jan van Royen (1711-1774) in 1776. The other copies have arrived via Doedes, and his notes can still be read on the flyleaves.

From Bremen to Utrecht

The French-German historian Isaac le Long was the first to turn his attention to the Heidelberg Catechism in a long period of time (1751, 111; 1760, 3-7). He had seen the first edition at his son in law, Johannes Christoph Busing, a clergyman in Hanau, and later a professor in Bremen. From his library the first edition was obtained by the Bremen priest Georg Gottfried Treviranus (1788-1868) who gave it to his colleague Gottfried Menken (1768-1831). When he died, Treviranus bought it back. Albrecht Wolters from Bonn visited Treviranus and published a facsimile edition based on his copy (1864). In 1866 J.J. van Toorenenbergen from Utrecht became the new owner. He sold it for one hundred Dutch guilders to Willem Jan Royaards van den Ham (1829-1897) and A. Royaards van Sherpenzeel. These two good and wealthy friends of Doedes donated the copy to Utrecht University Library. It is now known under call number E oct 1271 rar.

From Leipzig to Utrecht

A year later, in 1867, Doedes discovered that another copy of the first edition was up for sale in Leipzig. Utrecht bookshop Beijers made a successful bid and resold it to the Utrecht theologian students’ union Sodalitas Theologica Filaletheia which donated it to Utrecht University Library (Doedes 1869, 470-1). Call number is now E oct 1271* rar.

From Bonn to Utrecht

The copy from the third edition comes in possession of Albrecht Wolters as is also shown by his notes on the flyleaves. Right after it had became known that he wanted to sell it, Doedes found a friend willing to pay the money and donate the copy to Utrecht University Library. Doedes (1867, 35) indicates that the donor wished to remain anonymous, yet in his preface (xv) he mentions Christiaan Willem Johan baron van Boetzelaer van Dubbeldam (1806-1872) in such a way that one may presume that he was the benefactor.

The Lower Saxon and Latin translation from 1563

The Lower Saxon translation from 1563 (F oct 1399 rar) is the only known copy in the world housed in a library open to the public, even though at the end of the 19th century two other copies were in circulation. This copy came from the library of J. van Dam van Noordenloos in Rotterdam, where Doedes discovered it in June 1866. The Latin translation is more generally known than the first German and Dutch editions. Our copy E oct 159 rar is from the collection of Huybert van Buchell.

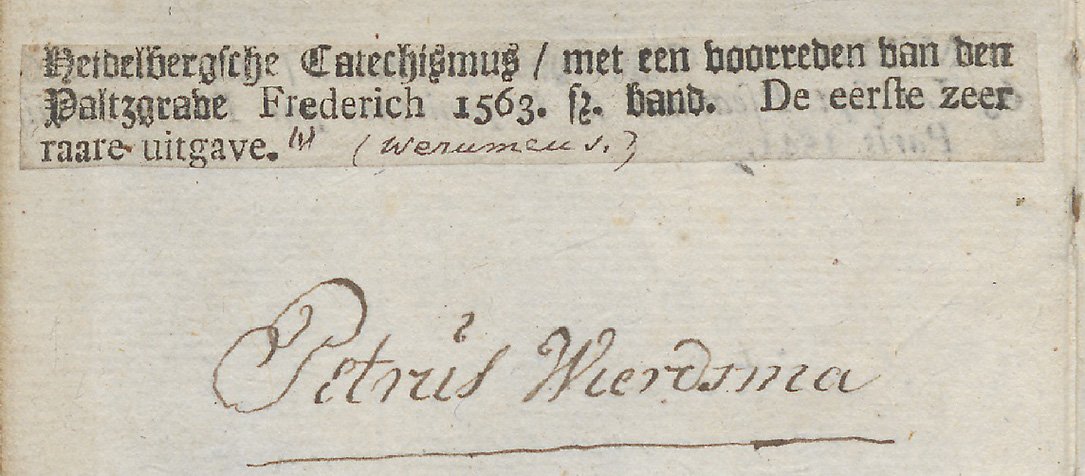

The first Dutch edition from Emden

The only known copy of the first Dutch translation printed in Emden in 1563 was discovered by Doedes in July 1866 in the library of I. Meulman in Amsterdam. It is not the copy Le Long wrote about, it was sold in 1858 from the estate of the Frisian jurist Petrus Wierdsma (1729-1811) whose name is written in E oct 1385 rar. Probably it belonged earlier to E.G. Coldewij who was employed as the count’s archivist for East Frisia (Doedes 1867, 89; Heijting 1989, I, 232 – B 12.1; II, 181). In January 2013, on the occasion of the 450th anniversary of the Heidelberg Catechism, a facsimile edition was published of the first Dutch translation by Van Wijnen in Franeker, in the luxury edition with an introduction by professor Wim Verboom. A facsimile has also been made of the first German edition. Both editions are based on the Utrecht University Library copies.

A lost and a given copy

The second Dutch translation of the Heidelberg Catechism by Petrus Datheen, printed in Heidelberg in 1563, came in Doedes’ possession in 1874 before it would be put up for auction by the Arnhem firm J.A. Nijhoff from the library of Gerdes (Doedes 1876, 37-48; Heijting 1989, I, 233 – B 12.2). The whereabouts of this copy is unknown. The only copy of the Emden edition of 1565 is the one which Doedes bought from the collection of Professor Constant Philippe Serrure (1805-1872) in Brussels. It came from the library of Professor Jan Frans van de Velde in Gent. Later he donated it to the Heidelberg University Library, call number Q 7188 4 A RES (Doedes 1876, 56; Heijting 1989, I, 234 – B 12.3; II, 182).

Emden editions

At the same Brussels auction Doedes also bought a unique Emden edition from 1566 (printed by G. van der Erven), which is very similar to the first Dutch edition. It also came from the library of Van de Velde and is now E oct 1485 rar Br (Doedes 1876, 56; Heijting 1989, I, 236 – B 12.5; II, 186). At the earlier mentioned J. van Dam van Noordenloos he also found a Dutch translation by Gaillart printed in Emden in 1566 (now E oct 1282 rar), with numbered questions. This copy used to belong to the Utrecht professor of Theology Jodocus Heringa (1765-1840) (Doedes 1867, 102-11, 118-120; Heijting 1989, I, 237 – B 12.7; II, 189). It contains the ‘mixed recension’ with influences from the first translations as well as Datheen’s translation.

Peter Datheen

The oldest edition of Datheen’s De Psalmen Davids en ander lofsanghen wt den Francoyschen Dichte in Nederlandschen ouerghesett (with musical notation) also contains his translation of the Heidelberg catechism, numbered and divided into 52 Sundays and printed in Heidelberg. Doedes also obtained this copy from Serrure’s collection (D oct 1297 rar) (Heijting 1989, I, 238 – B 12.8; II, 190). Also of the ‘mixed recension’ printed by Steenbergen in Deventer the University Library owns a copy (E oct 187 dl 3 rar), coming from the legacy of Evert van der Poll (Doedes 1867, 112-115; Heijting 1989, I, 241 – B 12.12; II, 199).

Unique copies

Although it is possible that not all early editions of the Heidelberg Catechism are recorded, it can be said with confidence that the Utrecht collection is unique in the world. This is mainly due to Doedes, by whose efforts several copies have probably been saved from oblivion. The collection as a whole gives a good picture of the crucial first years of the Heidelberg Catechism, and the complex history of its distribution in Germany and the Netherlands. In spite of the work of Doedes and many others this is a topic which still is in need to be examined further.