Being raised in a bilingual household and speaking fluent English or German as well as Dutch might sound ideal to some. But what if the two languages are Berber and Moroccan Arabic? Or Arabic and Armenian? Those combinations might raise some eyebrows, along with concerns that a multilingual upbringing could be a disadvantage for the child and exhortations to have them learn to speak Dutch as quickly as possible. But attitudes like that are no help to newcomers to the Netherlands. When children are proud of their own language and are allowed to use it in class, they can learn a new language even faster. New immigrants bring valuable knowledge of language along in their luggage. And we should take full advantage of it, rather than leaving it stuffed away in a suitcase in the attic. At Utrecht University, we help children, parents and teachers make the best use of the valuable contents of newcomers’ language luggage.

A home filled with languages

Estimated reading time: 15 minutes

Being multilingual is the norm in our neighbouring countries, and increasingly in the Netherlands as well, thanks to the many languages and dialects that are spoken here. On the one hand, we encourage children to be multilingual: the calls for bilingual education and child care are becoming ever-louder. But that enthusiasm is very selective, and limited mainly to English, German and French. Learning languages other than these three is often accompanied by concerns about delayed development and mixing languages. But being multilingual isn’t the problem; it is the persistent myths about multilingualism that stand in the way of children’s opportunities. Utrecht University linguists work to debunk these myths to make room for knowledge and practical tools for every child’s language development.

You shouldn't take away a child's own language.

Myth: Being multilingual leads to language deficiency

Being multilingual doesn’t stop children from learning Dutch. In fact: a rich selection of languages - any language - actually contributes to a child’s language development, and therefore to the ability to learn a new language. “Language is more than just words and grammar. Language also gives you guidelines for learning to count or understand abstract concepts, such as yesterday or tomorrow. You need language to learn abstract thinking and arithmetic,” says Utrecht University linguist Jacomine Nortier.

“A child who can count in Moroccan, but doesn’t know a word of Dutch, is farther along in their development than a Dutch-speaking child who can’t count. You definitely shouldn’t take away a child’s own language. A multilingual child’s vocabulary in each individual language is often somewhat smaller than that of a child who only speaks one language, but their language development progresses quickly. And that’s what’s important: children need to develop their language skills, and it doesn’t matter in which language. We should really welcome the languages they speak at home. They don’t come at the cost of learning Dutch, as many people think. Every language has something to offer.”

Myth: Being multilingual is a problem

“Being multilingual is the norm around the world, and even in the Netherlands many people speak multiple languages or dialects, which is also considered to be multilingual. In Papua New Guinea, children even learn four or five languages at the same time. There is absolutely no evidence that children suffer from being multilingual,” says Elma Blom, Professor of Language Development and Multilinguality, who studies children growing up in a multilingual environment. The fact that multilingual students occasionally score lower can often be attributed to their social or cultural background, or to testing systems that are not designed for multilingual children, but not to multilingualism itself.

On the contrary; there is mounting evidence that multilingualism actually provides a cognitive benefit, such as improved ‘executive functions’. “You use executive functions when you need to concentrate on a task and ignore distractions,” Blom explains. “Multilingual children are constantly training that skill. Our research has shown that Frisian-Dutch, Polish-Dutch and Turkish-Dutch children have an advantage in performing tasks that require attention and concentration and the use of their working memory.”

Blom adds that the more balanced the child’s bilingualism – using both languages the same amount – the greater the cognitive benefit. That is an argument in favour of making room for the languages the child speaks at home, because as Blom explains, children do not actually ‘soak up languages like a sponge’. “The language offerings and use of language determine the degree to which children learn a language. Their mental capacity isn’t the problem; it’s the exposure to a high quality language offering. So it’s important for children to keep hearing and using their mother language or languages.”

As a non-Dutch parent, you shouldn't try to speak Dutch to your children.

Myth: children should also speak Dutch at home

There are other reasons why continuing to speak their home language is important for children: “As a non-Dutch speaking parent, you shouldn’t try to speak Dutch with your children. It doesn’t contribute to them learning Dutch correctly,” says linguist Manuela Pinto. Speaking, reading and being read to in the language spoken at home reinforces the child’s language development, and therefore their ability to learn new languages. “When children are made to feel that the language they speak at home is ‘not done’, or that they should be ashamed of their home language, then they’ll simply speak less. Children can sense that, and it stands in the way of their development of other languages.”

Dutch will eventually become the dominant language for children through school, friends and the neighbourhood. Parents don’t have to make an extra effort for that, says Pinto, who also gives workshops for parents of multilingual children. “We often observe that children stop speaking their home language around grade 3 or 4, but even then, it’s still a good idea (and more natural) if parents continue to talk to them in their own language,” says Pinto, who continued to speak Italian to her child even when he stopped speaking it himself. “Children understand it just fine, so they effortlessly become proficient in multiple languages, which can only benefit them throughout their lives.”

We should be giving the children's home language a place in the classroom.

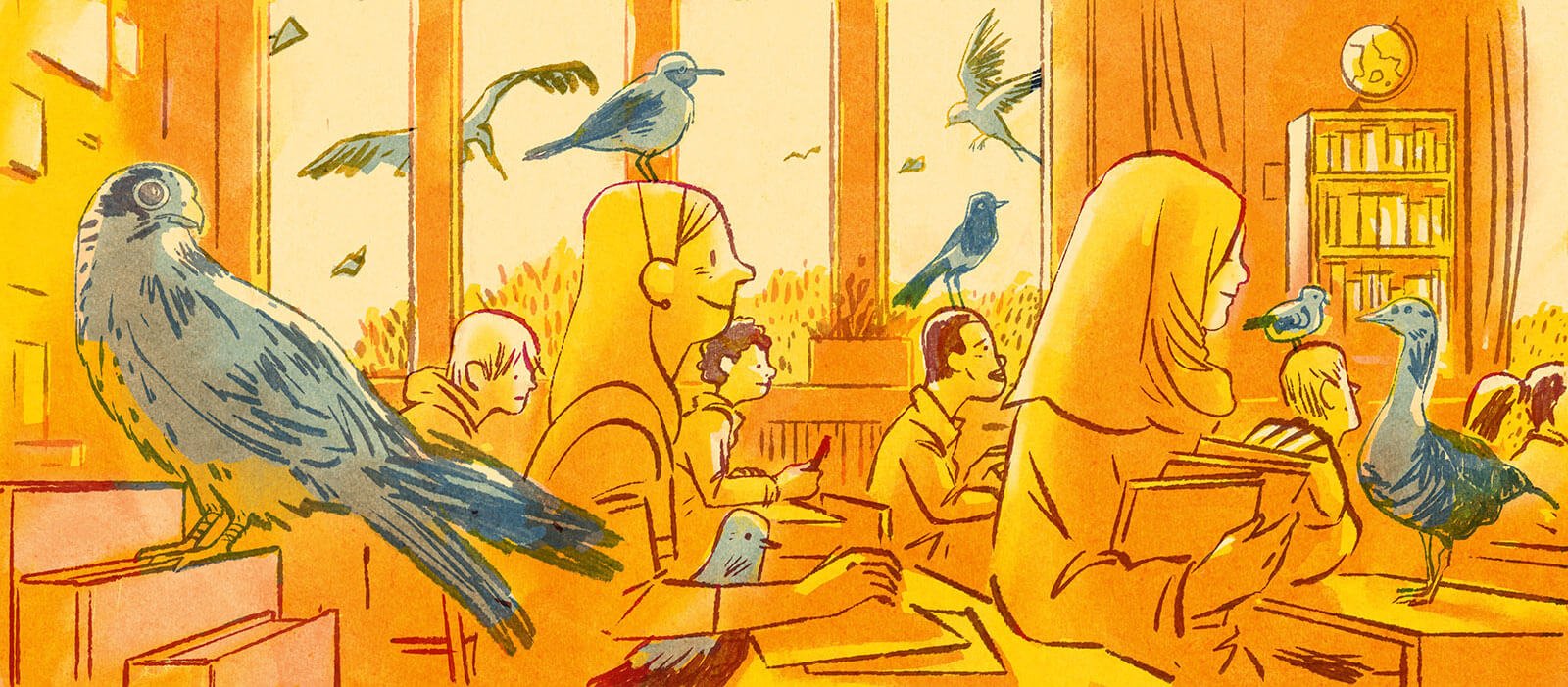

Myth: children should only speak Dutch in class

Schools that proudly display signs saying ‘We speak Dutch at school’ should take a moment to reconsider. “We should actually be giving the children’s home language a place in the classroom,” says linguist Sergio Baauw, who is an advocate for the strategic use of children’s home language. “That doesn’t mean they should just speak whatever they want. For example: explain the lesson in Dutch to the entire class, then have the children do an assignment in another language, and let them explain the result of the assignment in Dutch.”

Children speaking together in another language does not pose a threat to their education or their ability to learn Dutch. “Their home language actually helps them to acquire knowledge or skills that they aren’t yet able to in Dutch, and they can help one another when they don’t understand the teacher’s explanation in Dutch.”

Refugee children often carry an especially large suitcase full of languages. “You have to realise that some children have come a long way to get here. That makes them exceptionally sensitive to language,” says Baauw. “Maybe they come from Syria, where they learned Syrian Arabic, then stayed a while in Morocco where they spoke Moroccan Arabic, came into contact with Spanish and Catalan on their way through Spain, then picked up some French, and now they’re learning Dutch. As language researchers, we see all that as resources the children can use, and we should let them use it much more at school.”

Myth: every parent should speak a single language with the children

But what if children mix all of those languages together? To prevent language mixing, parents have long been advised to use the strategy: one person, one language (OPOL). In a German-Kenyan family, for example, the mother might only speak German with the children, the father Swahili, and the parents speak English together. But today, language researchers don’t recommend such a strict separation. There is little evidence that it is beneficial for learning a language. And too strict a separation is even undesirable: the children either don’t know the words to talk about school at home, or have difficulty telling their mother about an outing with their father.

Language mixing can be a sign of a child's creativity.

“Multilingualism doesn’t mean that it’s chaos inside the children’s heads. They can separate their language systems from a very young age, and they know very well with whom they can speak which language,” explains Blom, who recently received a VICI grant for his research into language mixing. And it isn’t necessarily a problem if children do mix languages. “Sometimes children mix languages to fill gaps in one language with words from another. But it could also be a sign of creativity or a large vocabulary. Language mixing may be correlated with weak language skills, but it can also be an indication of a child’s power of expression.”

Street language

Moreover, language mixing can be context-dependent. This is clearly seen in street language, a mixed language that young people from different cultural backgrounds speak alongside Dutch. "Street language is not a sign of poor knowledge of language, but rather a demonstration of good command", says Nortier. "In different contexts they speak different languages; in a job interview they will certainly not speak street language. They can apply it functionally."

It’s time we stop seeing multilingualism as a problem, and start seeing it as an enrichment. But that doesn’t mean the language a child speaks at home can’t have an impact on the class, the teacher or how the child learns Dutch. Because the specific language spoken at home has a major influence on learning a new language, as does the person’s individual circumstances: whether they are an immigrant, an asylum seeker or an expat. Embracing the languages spoken at home also entails taking the person’s background into consideration at school and in society at large. Researchers in Utrecht are developing a wide range of methods and instruments to help with that.

Web app for home languages in the classroom

“Your mother tongue has a major influence on learning Dutch, because there are some major differences between the characteristics of each language,” Nortier explains. “For example, Chinese, Vietnamese and Indonesian don’t have plural suffixes. Russian and Berber don’t use articles, and Turkish doesn’t differentiate between ‘he’ and ‘she’. Moroccan Arabic does use articles, but they don’t correlate to the masculine/feminine ‘de’ and the neuter ‘het’ in Dutch. If you as a teacher are aware of these characteristics, then you know which concepts will be difficult for your student.”

Linguist Sterre Leufkens has developed the web application Moedertaal in NT2 (MoedINT2) especially for educators, based on one of Nortier’s ideas. “Experience has shown that teachers often have trouble dealing with problems specific to a student’s mother tongue. They don’t know the differences between Dutch and every other language in the class, and they don’t have exercises on hand to practice those differences with the student.” The program helps them with that. In the web app they can find overviews of crucial differences and similarities between Dutch and several common native languages, with exercises for each. That way, they know exactly which student will have difficulty learning articles, prepositions or adverbs, and how to help them.

New methods for measuring language development

To learn more about Dutch language and culture, children who are new to the Netherlands sometimes attend language courses before transferring to a standard school. It can be difficult for educators to determine which primary school grade they should be assigned to, however, because there is no instrument available to measure their language development and knowledge. “The tests are geared towards multilingual children, but a bilingual child is not simply the sum of two monolingual children. As a result, newcomers always receive a lower assessment,” explains linguist Shalom Zuckerman, who developed a new method together with Manuela Pinto to test multilingual children’s language proficiency.

Zuckerman and Pinto had already collaborated on the Coloring Book method, which is suitable for monolingual children. “We use it to test their language comprehension in a playful manner. The children can colour in objects based on sentences like ‘the table is red’ and ‘the tablecloth is blue’. Their actions show what they know, but to the children it feels like a game: they don’t realise they’re being tested,” Zuckerman explains. “Plus, it gives them fewer opportunities to just guess the answer than standard tests with multiple-choice questions. And the fact that the colour method puts concepts in a context is a big plus,” Pinto adds.

Zuckerman and Pinto are currently working on a new instrument – Nederlands voor alle kinderen (Dutch for all children) – to more accurately identify newcomers’ language development. “Teachers can use it to monitor individual children’s language process, geared to their age and circumstances such as their mother language, whether they already know the Latin alphabet, and how long they’ve been in the Netherlands. That allows teachers to make a well-founded recommendation as to the right place for the child to integrate into a standard school,” says Zuckerman. “We’ve noticed that there’s a lot of demand for a tool like that among educators.”

We also don't demand dyslexic children that they learn to read and write fluently and flawlessly before they go on to university preparatory education.

New test policy for newcomers

The standard testing system also has room for improvement when it comes to taking multilingualism into consideration. “Like how we do for dyslectic children: we give them more time, and special reading materials. You can’t demand that they learn to read and write fluently and flawlessly before they go on to university preparatory education; that would be unthinkable. So why shouldn’t we treat newcomers the same way we treat dyslexic children?,” asks Baauw, who advises schools about newcomers as part of the EDINA project (EDucation International for Newly Arrived migrant pupils).

At the moment, newcomers often receive a recommendation for vocational education after primary school due to their ‘unsatisfactory’ language proficiency level, even though they may be capable of successfully completing higher education. Research has also shown that children can make up early language deficiencies later on. “We desperately need more plumbers, of course, but it should be the individual’s own choice,” says Baauw. “We have an obligation to help these children realise their full potential.”

That starts by raising awareness, explains Baauw. As research leader of the EDINA project, Baauw brings schools, policymakers and researchers together to help municipalities, schools and educators with the integration of new immigrant students in the education system. “We use an online platform to offer teachers all sorts of tools that can help, like formulating a different testing policy, a different language policy, and dealing with linguistically and culturally diverse classrooms. We’ve noticed a shift towards acceptance of the languages spoken at home, but it’s a slow process.”

Multilingual children with language disorders

The biases about multilingualism often result in newcomers not receiving care or guidance when they do have a language-related problem. “Congenital language defects are hard to diagnose, and they’re even more difficult among newcomers. People almost automatically assume that they have a language deficiency, and any difficulty with language is quickly attributed to their being multilingual,” says Blom, who is working on various instruments for diagnosing a language development disorder in multilingual children.

That is because current methods are based on monolingual or Dutch-speaking children. “A child who just arrived in the Netherlands will naturally score lower on a Dutch language test. But if they also score poorly in a test in their native language, then they may have a language disorder. Unfortunately, it just isn’t possible to find speech therapists for every native language.”

So how can you test whether children have a language disability? “By deliberately avoiding the specific language,” says Blom. “One of the things we’re developing is a method for testing language skills using made-up words with sounds that occur in every language, like ‘kazulumi’. That’s because children with a language disorder have difficulty repeating non-existent words; a skill they also need to learn a new language. We’ve already observed that multilingual children score better on this new test than on standard tests. An estimated 5.8 million children in Europe have a language development disorder. The sooner a disorder is diagnosed, the sooner children can receive the help they need.”

Welcome in your own language

The researchers from Utrecht argue that all of the different languages spoken at home should be more visible in society. “Language is more than just the transfer of information. Even if you’re proficient in the language, it’s still nice to read a poem on a wall in your native language. Or if you know that a lot of Japanese visitors take the bus to the Nijntje Museum, why not show the bus destination in Japanese?,” asks Nortier. “Even if a lot of people can get by just fine in English, they feel more welcome and involved when approached in their native language.”

As part of the European LUCIDE project (Languages in Urban Communities – Integration and Diversity for Europe), Nortier studied good practices regarding multilingualism in several different cities, for example in fields such as health care, business and the public sector. That included creating toolkits for using multilingualism in a positive and creative manner. “For example, when people are welcomed in their own language at the health centre reception desk, it puts them much more at ease,” says Nortier. “Just a few words are enough.”

Languages spoken at home should also be given a more prominent place in science museums. “Science museums are one of the contexts in which children learn. But they can rarely use their home languages in this context. By using languages spoken at home more often, you give children an opportunity to learn, participate and feel welcome,” says Blom, who studies the issue as part of the Multi-Stem project. Some options include putting up signs in multiple languages, multilingual digital offerings, buddies who can accompany the children in their own language, or pre-teaching videos about the exhibition that they can watch at home.

These are some minor adjustments, but they can have a major effect: “The great thing is that it also has a positive effect on the parent-child relationship. Imagine how it must be for parents who can’t speak Dutch, and therefore can’t help their child with an explanation. That not only has an effect on children, but also an enormous impact on parents as well. By offering information in several languages spoken at home, parents can finally perform their role as parents again.”

The Netherlands is becoming richer and more diverse, and gaining new languages and cultures all the time. So it is time that we understand that multilingualism doesn’t stand in the way of the Dutch language. New languages are a valuable addition, and not just for linguists. All of those languages play a role, both in the Netherlands and the process of learning Dutch. We are improving our understanding of how to take that into consideration, in the classroom and in society at large. With the knowledge and practical methods developed by Utrecht University’s researchers, we can also help multilingual children become more proficient in Dutch. So that newcomers can truly feel welcome in their new home. Because the Netherlands is what we make of it together.