Seventeenth-century language education challenged young people to experiment with language

While in our time there are concerns about the reading and writing skills of Dutch young people, in the seventeenth century the Netherlands was the most literate country in Europe. What did language education for young people look like then? In an article for the journal Early Modern Low Countries, Prof. Els Stronks, Professor of Early Modern Dutch Literature, shows that the didacticians of the time mainly allowed young people to experiment with their own use of Dutch.

Stronks examined dozens of dictionaries and textbooks on grammar, pronunciation and word structures, published for young people between 1546 and 1750. She found that these books did much more than prescribe language rules and convey the meaning of existing words: they also challenged young people to observe their own language use as an object of study, and thus to develop new knowledge about language.

Feeling Tones

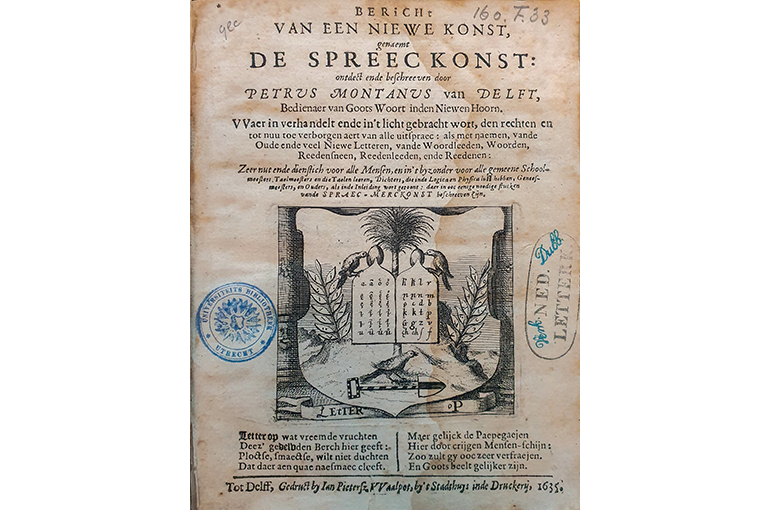

For example, many textbooks encouraged students to compare with what they already knew from their own language use, and thus to observe this language use. To learn more about sentence structures, for example, you could make comparisons between the same sentence in different languages, and to understand how to pronounce a foreign word you could compare the sound with that of a familiar word. In one of the first books on pronunciation, Petrus Montanus' Bericht van een niewe konst, genaemt de spreeckonst from 1635, the student is even advised to put their finger in their mouth to feel how sounds are formed. Dictionaries, moreover, invited the reader to think about how language constantly renews itself by presenting not only already known words but also new ones. Again and again, therefore, an important role in learning Dutch was for young people themselves to experience the power of language, Stronks said, "Feel what sounds you make, think about how you write them down, think about the meaning that words have for you. There were norms that these books made young people aware of, but they also pointed to the space that language offers for one's own expression and self-chosen form."

Writing in your book

To encourage experimentation with their own language, young people were also advised to take notes in their textbooks. The design of some books was also specially designed for this purpose, with a blank page for notes after each printed page. There the students could write down, for example, interesting words they came across in other books. In some surviving copies this is indeed what happened.

Seventeenth-century language books pointed out to young people the space that language offers for their own expression and self-chosen form.

Language as gateway to knowledge

An inquisitive attitude was not only encouraged in order to learn the language: the textbooks also emphatically presented language knowledge as a means of opening the door to other fields of knowledge. Because so many children were taught language in the seventeenth century, Stronks suspects that the methods used there also influenced the emergence of a more experimental attitude in other subject areas. Until now, researchers have often assumed that children's literature and textbooks did not begin to encourage observation, experimentation, and curiosity among young people until the eighteenth century - at the time of the Enlightenment. Stronks' research shows that such attitudes were encouraged much earlier, in the sixteenth century.

Dynamics of Youth

As professor of Early Modern Dutch Literature, Stronks not only looks at language education in the past, she is also the initiator of several projects that want to make language education more appealing today and let young people experience for themselves how powerful and beautiful language can be. Even now, experimenting with and thinking about your own use of language is an important way to increase language knowledge. This happens, for example, at the Schrijfakademie and in the Taalbaas master classes. With this historical and contemporary expertise, Stronks makes an important contribution to Dynamics of Youth, the UU-wide research theme on growing up. In an interview about this research theme, she explains why historical awareness is indispensable in youth research: "How our youth develops cannot be seen separately from Dutch culture, language, and historical thinking about upbringing and education in the Netherlands."