Spain’s Machiavellian plan to green-wash the National Energy and Climate Plan

This blog was written by Júlia Isern Bennassar as part of the Master Law and Sustainability (2022-2023) at Utrecht University School of Law .

Greenpeace et al v. Spain:

Almost unnoticed by the European and even Spanish media, Spain has joined the group of countries that are being sued for not doing enough to fight climate change and therefore for putting at risk the lives of the present and future generations. The reason is Spain’s lack of ambition in its Nationally Determined Contribution. In March 2021, Spain published the National Energy and Climate Plan which stated a reduction target of greenhouse gas emissions of 23% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels. Is this goal in line with the Paris Agreement and with the scientific data presented by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)? The Spanish Government, backed by the European Commission, assures that it is, while a group of Spanish NGOs think otherwise and have sued the Government, inaugurating the so-called “Juicio por el clima” Júlia Isern Bennassar

Opening remark

Before diving into the minutiae of the case it is imperative that we define what Greenpeace et al v. Spain is. Following the most recent literature, Catherine Higham has baptised “Framework litigation” the “litigation in which litigants challenge aspects of a national or subnational government’s overall policy response to climate change”. This is where our case of study lies: a group of NGOs challenging Spain's Energy and Climate Plan for inadequately tackling climate change. This is nothing new. Encouraged by the triumph of State of The Netherlands v. Urgenda Foundation, many NGOs have filed claims against national or local governments accusing them of not doing enough to address climate issues (see A Sud v Italy, ClientEarth v. Secretary of State, Notre Affaire à Tous and others v. France). Now it’s Spain’s turn to be put on trial. In September 2020, Greenpeace Spain, Ecologistas en Acción-coda and OXFAM Intermón (hereinafter ENGOs or claimants) initiated a judicial process against the Spanish Government that will mark a milestone in the fight against climate change in Spain.

Background

According to article 3 of Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 on the Governance of the Energy Union and Climate Action, “Each Member State shall notify to the Commission an integrated national energy and climate plan” by 31 December 2019. Unsurprisingly, Spain failed to comply with this deadline which led the claimants to file a motion against the Supreme Court for the failure of Spain to approve a legal national energy and climate plan. In the meantime, the Spanish government published the National Energy and Climate Plan (hereinafter PNIEC) in March 2021. The PNIEC presents four main goals:

- Reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 23% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels

- Increase the share of renewable in total consumption by 42%

- Improve energy efficiency by 39,5%

- Increase renewable energies in the production of electricity by 74%

The low target for GHG emissions established by the PNIEC led the same ENGOs to file a second claim against the Supreme Court, using the same legal arguments as in the previous one. Before moving forward to the legal analysis, it is necessary to establish why this claim is of the utmost importance in Spain.

Spain and climate change

The IPCC has placed Spain as one of the most vulnerable countries to the effects of climate change. The year 2022 was the warmest year ever recorded in Spain and the third driest. Only last year, 270.000 ha were burned and 5.665 people died from causes directly related to the high temperatures. Moreover, 80% of the Spanish Pyrenean glaciers have already disappeared and 20% of Spanish territory falls under the category of a desert (with the risk of becoming 75% desert by the end of this century). The constant increase of the sea temperature, the over-construction, and the rise of temperature are leading to a 40-60% loss in biodiversity in what is the most biodiverse country in Europe.

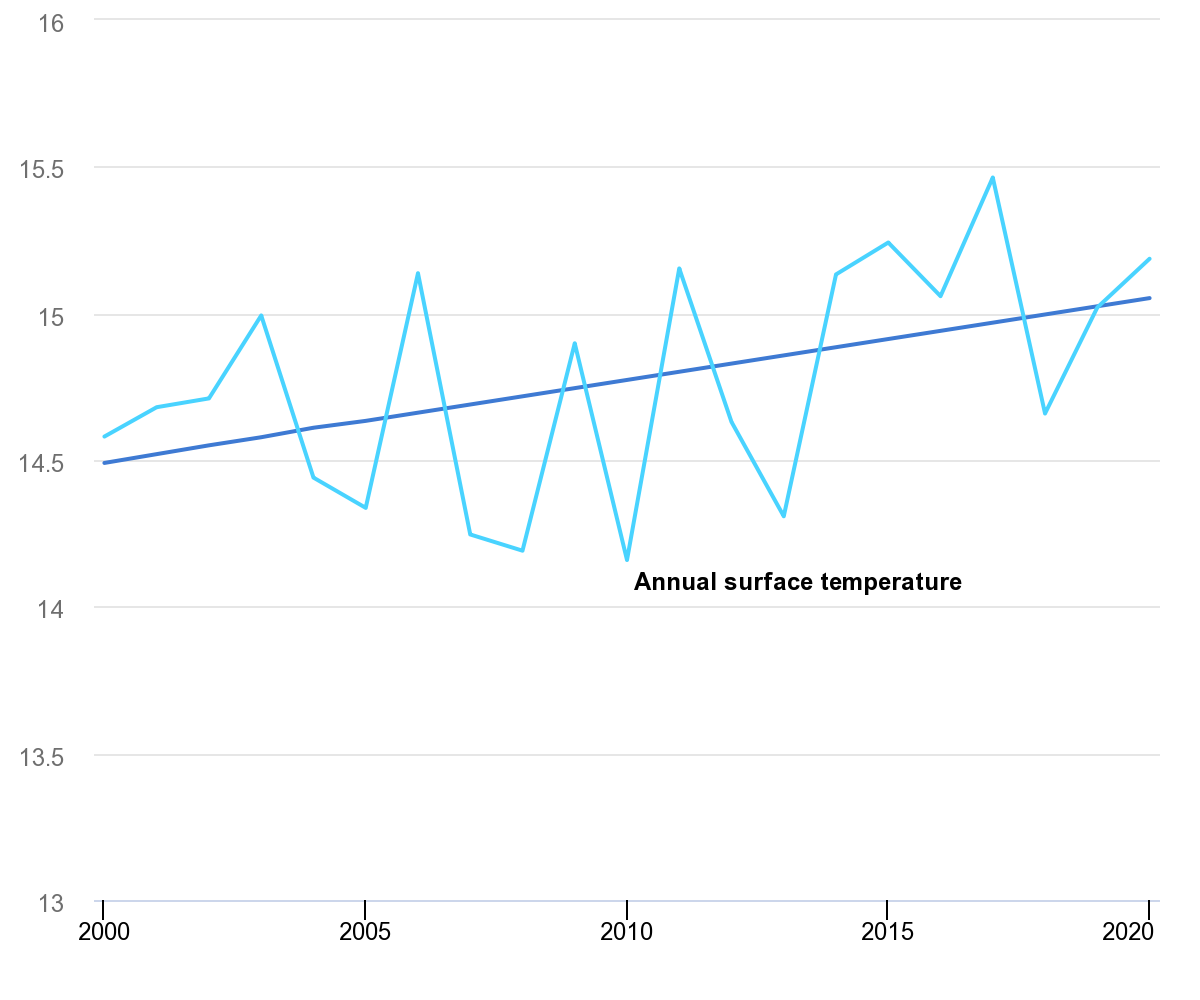

According to the Spanish National Communication to the UNFCCC, NC8, Spain’s average temperature has increased by around 1,5ºC in the last 50 years (vs 1,2ºC globally). This all shows that the emergency in Spain is particularly grave.

It’s important to have a brief overview of Spain regarding GHG emissions. They represent 0,63% of total global emissions. During the first years of the 21st century, it increased its emissions abruptly, reaching its peak point by 2005 (see table 2), after which it declined due to the economic crisis and not due to climate policies.

Temperature in Spain, 2000-2020

Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions in Spain, 1990-2019

Legal grounds of the claim

The ENGOs based both claims on three main arguments:

- Non-compliance with the Paris Agreement,

- Violation of articles 2 and 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights,

- Lack of effective public participation and environmental impact assessment.

In this publication, we will focus on the infringement of the Paris Agreement and how the PNIEC is condemning future generations.

With the Paris Agreement, a binding international treaty, parties agreed on limiting the rise of temperature to below 2ºC. However, since scientists reported that crossing 1,5ºC would have irreversible effects, at COP 26, parties reconfigured the goal to below 1,5ºC. As a result of the Agreement, each party had to publish its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), where parties had to include targets to attain the agreed goals. (Note: Spain’s NDC was stated in the PNIEC: 23% reduction target of GHG emissions.)

The Paris Agreement was ratified by Spain in January 2017 and became part of its internal legislation through article 96 of the Spanish Constitution. Hence, Spain is obliged to comply with the content of the Agreement. According to the claimants, Spain doesn’t have a large discretion to determine its NDC because the Paris Agreement sets a very high level of protection. They claim that the only legal NDC is the one which requires Spain to do everything it can to contribute to holding the temperature below 1,5ºC. The basis of the claim is that there’s enough scientific evidence, provided by the IPCC reports, to prove that Spain has to set more ambitious goals. In this regard, the ENGOs request the Supreme Court to call upon Spain to improve the current NDC to a reduction target of 55% by 2030 from 1990 levels, arguing that this would be in line with international law and with Spain’s fair share.

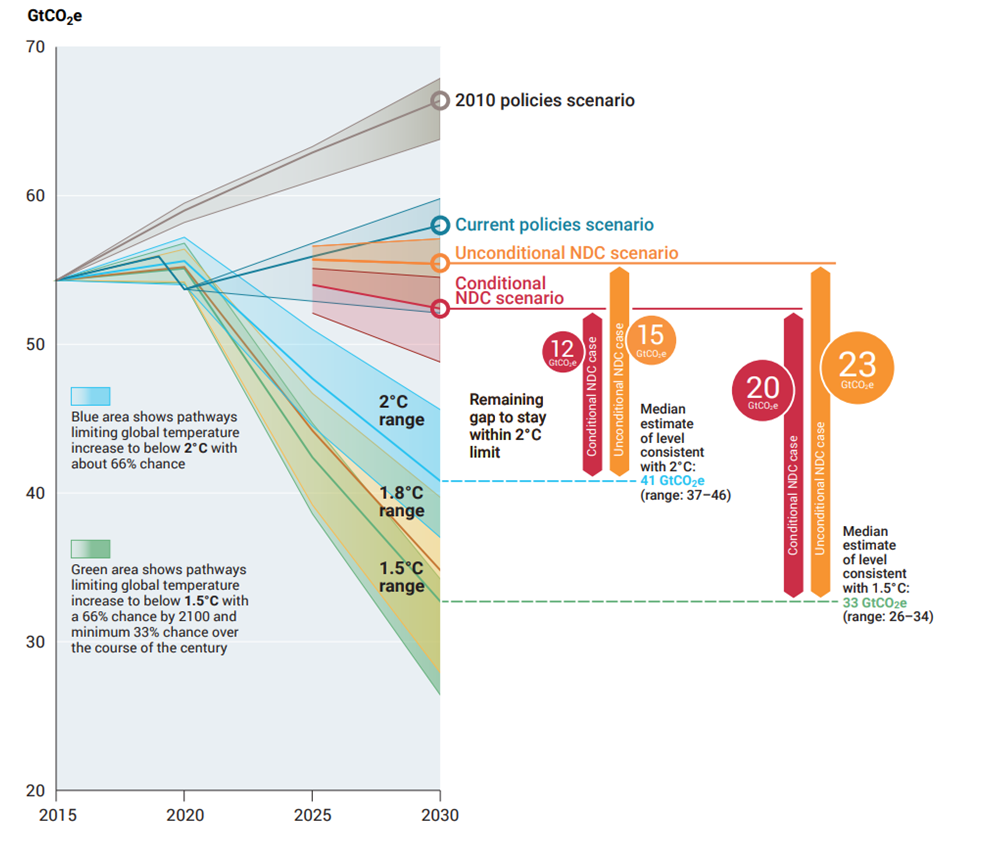

The claim is also in line with the emission Gap Report 2022 that concluded that “the international community is falling far short of the Paris goals, with no credible pathway to 1.5°C in place”, demanding for more rigorous policies (see table below).

But, what does it involve setting the NDC so low?

The Government, supported by the private electric companies and the European Union, has argued that this target is sufficient to reach climate neutrality by 2050. With this, Spain is accepting that from 2030 until 2050 the Government will have to take much more stringent measures. What hides behind this is a brutal sentence to future generations that will have to make larger investments in order to reach climate neutrality. Besides, the longer we wait the higher the uncertainty of the effects of climate change are, as Johan Rockström argues, in his theory of planetary boundaries, there’s no scientific data to know what will happen once we surpass a tipping point. Therefore, setting a reduction target of 23% is against the international environmental principle of intergenerational equity.

What’s next?

In the words of Jaime Doreste, one of the two leading lawyers in the claim who was interviewed for this publication, the best outcome of Greenpeace et al v Spain would be the establishment by the Supreme Court of a new target for GHG emissions, according to the scientific evidence submitted by the claimants, preferably the suggested 55%. This would oblige the Spanish Government to modify the NDC and promote more drastic policies. However, this result is very unlikely due to the conflict of separation of powers that could arise from it, since the judiciary cannot determine the content of a measure.

The truth is that there’s a big chance that the Supreme Court will determine the illegality of the PNIEC for lack of formal requirements. If that happened, Spain would again be left without an instrument to regulate energy and climate. When posed with such a dilemma, the claimants accepted the risk and decided to continue with the claim.

Concluding remark

Acquiring an adequate standard of living in Spain is turning into an impossible feat. The quality of life in this highly desirable holiday resort is diminishing as a result of strong heat waves, intense rain and flooding -which is causing big infrastructural losses-, ongoing crop failures resulting from abruptly changing weather conditions, and arrival of new plagues. Meanwhile, Spaniards are resigned to it, because they feel that not much can be done to prevent it. This is where the Spanish Government is playing a Machiavellian plan; it’s selling the PNIEC as the road for a sustainable future, an ambitious policy that will put them on the front line to combat climate change, while the target of 23% is clearly not in line with the Paris Agreement. This makes the emissions reduction target of the PNIEC nothing more than a real pantomime. As it is argued by the claimants, the PNIEC has to set a reduction target for GHG emissions that falls within the goals of the Paris Agreement; that is aiming at a high level of ambition to really contribute to holding the temperature below 1.5ºC. The ambitious policies must be taken now and not put the burden on future generations, which goes against the principle of intergenerational equity. Much more can be expected from a national Government that is supposed to grant a future to its population.

This article was originally written by Júlia Isern Bennassar as a blog post assignment for the master Law and Sustainability in Europe (EU Climate Protection) 2022-2023, which is organised by the Utrecht Centre for Water, Oceans and Sustainability Law.