I want to increase the awareness about the enormous importance of a healthy environment for people and animals'

Juliette Legler aims to improve European tests for endocrine disrupting chemicals

As a child, Juliette Legler was already busy saving the environment and our beautiful planet. A fascination for nature and ecology and her passion for research eventually led her to the field of toxicology. Since 2018, Legler leads 'one of the strongest toxicology groups in the world'. With her research into the effects of endocrine disrupting substances (substances that disrupt how hormones work), she is building a bridge between environmental science and human toxicology. With that, the circle for her is complete.

'Hormones are incredibly important for a wide range of processes in the body', says Juliette Legler, environmental scientist and Professor of Toxicology at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine. 'Hormones influence the correct development of the brain and a wide range of organs during early life. Throughout our lives, they regulate many different important facets such as reproduction, development and our body's temperature.'

Hormone systems disrupted

Our living environment contains substances that can damage these hormones or disrupt their function, explains Legler. 'Examples are pesticides, substances in plastics, packaging, medicines, and cosmetics and also industrial substances such as flame retardants. These are produced by the chemical industry for very different purposes but can have undesirable side effects for the endocrine systems of people, animals and the functioning of ecosystems. As a toxicologist, I investigate how the substances can disrupt the endocrine system.'

Concerned about nature

Juliette Legler grew up in Canada. She was always outside, busy with plants, bugs and birds in the garden. 'From a young age, I've always been concerned about ecology and the environment. In Canada, I was surrounded by endless nature, and I loved that. At high school, I studied ecology, and that subject thoroughly fascinated me. I had a eureka moment when I realised life was all about connections: between people and animals, between different animal species and between animals and their environment! It was fantastic to see how all of that fitted together. So once I had finished high school, I went to study environmental sciences. Not because my family wanted me to but because of my own interest in ecology and the environment.'

During her study, Legler did an internship in the Netherlands where she gained her first experience with laboratory research and in toxicology. 'I enjoyed that so much! Toxicology is about how poisonous substances affect people and the environment. This subject offered me a way to protect both. So back then, I decided I wanted to be both a researcher and a toxicologist.' Over the years, Legler's research has increasingly focused on human health. 'Some people no longer consider me to be an environmental toxicologist because I have stopped working on bugs in the soil. However, it is humans who need to be made aware of the effects of substances around us. I consider myself to be a bridge between environmental and human toxicology.'

After a successful scientific period at VU Amsterdam and Brunel University (London), Legler was appointed Professor of Toxicology at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine in 2018. There she leads 'one of the best toxicology groups in the world'.

I consider myself to be a bridge between environmental and human toxicology

Why does this group have so much impact worldwide?

'We do well in the international rankings, and we really excel in certain niches. We have an international reputation in neurotoxicology, immunotoxicology and alternative models as well as my own research into endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs). For example, within the research of Remco Westerink, we have developed tests to assess the toxicity of substances on the developing brain, especially the effects of toxic substances on neurons. Martin van den Berg has played a worldwide leading role in the standardisation of dioxins. And my own research into the role of EDCs in obesity and diabetes is new and of international repute. I led the first European project in this, and so within Europe, I am a pioneer in this field.'

What is the link to veterinary medicine?

'Within toxicology, there is a veterinary branch concerned with the poisoning of domestic and farm animals. This is an important line of research in toxicology, and so we do teach this subject. I never thought that I would end up in a faculty of veterinary medicine, but to be honest, everything is intertwined. We should not forget that veterinary medicine is not only about the treatment of diseases but also their prevention. And that is where the environmental aspect is so important. I want to increase awareness about the enormous importance of a healthy environment for both people and animals and, as a toxicologist, I consider that to be my most important mission.'

One Health, One Toxicology

Returning to hormones and substances that disrupt their function. This is a subject that fits within the concept of One Health, which connects the health of people animals and the environment. One Health is also a strategic focus within the faculty of veterinary medicine. 'One Health really appeals to me', says Legler, and it also played a prominent role in her inaugural lecture "One Health, One Toxicology". 'The effect of hormones is very similar between people and other animals. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals affect various organisms and not just humans.'

The clearest evidence comes from field studies with fish or mammals in the environment. Several years ago, there was a famous case study. 'Fish that swim during their development in surface water contaminated with chemicals that mimic female hormones were found to become more feminine. Male fish then become far more similar to female fish, and that effect was so extreme that they developed both male and female reproductive organs. That is really drastic. The problem is mainly due to substances excreted by people, such as synthetic hormones in the contraceptive pill and other medicines that we take. These eventually end up in the environment.'

'The effect of hormones is very similar between people and other animals. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals affect various organisms and not just humans.'

That sounds disturbing…

'What is most disturbing is that we do not really know whether this is the case for many of the substances we produce, as they are not sufficiently tested before they are launched on the market. For pesticides, a wide range of animal experiments are done to test whether the substances are toxic for rodents, as a model for people, but hormonal changes are not measured in standard toxicity tests. These tests do not examine the more subtle effects that make an animal or person more vulnerable to diseases in the longer term. That is a significant shortcoming.'

Vulnerable to obesity

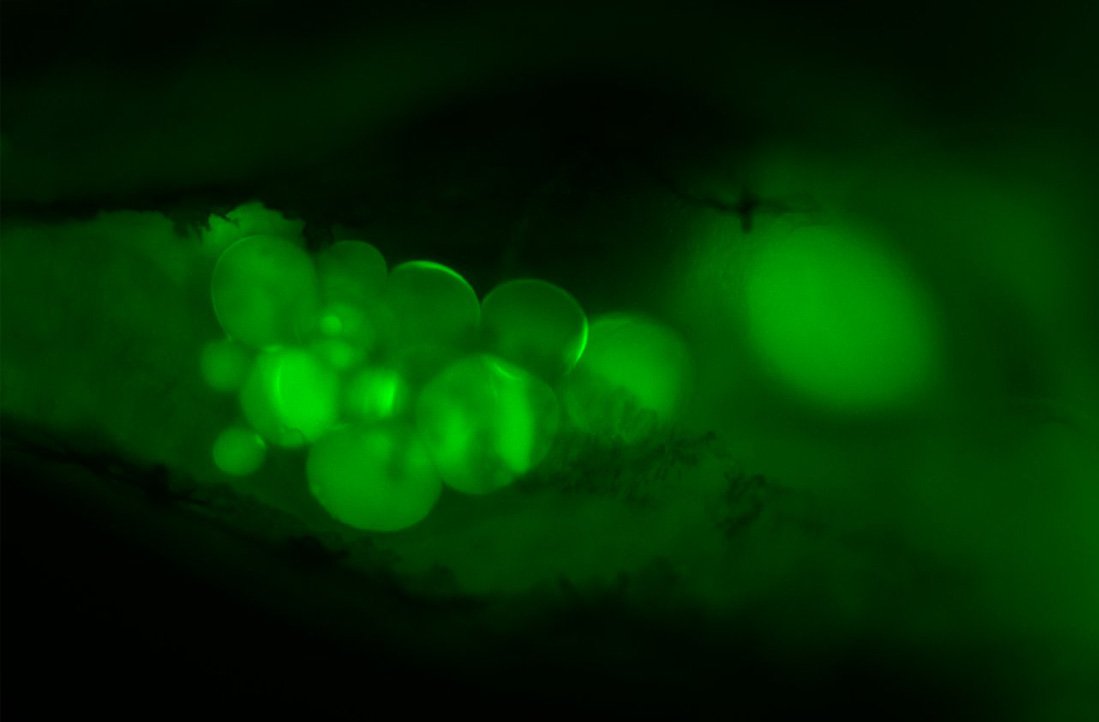

Since January 2019, Legler leads the Horizon2020 project GOLIATH, funded by the European Union. The project focuses on the influence of EDCs on the development of metabolic disorders, such as obesity, diabetes and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. 'We are currently examining how exposure to EDCs during development influences the development of fat cells. That research is already being done elsewhere with mice, but we are doing it with zebrafish as an alternative model. Under the influence of such substances, zebrafish form fat cells that are larger or function differently, for example. That makes an organism more vulnerable to become overweight.'

'There are not yet any validated, internationally accepted test methods for substances that possibly play a role in the development of metabolic diseases. That means a substance can be marketed, which has an undesirable hormonal influence on fat cells. According to the law, substances must be tested for their endocrine disrupting effect, but industry cannot satisfy this requirement if the tools are not there. That is an important omission. We must start with the development of simple, animal-free tests that manufacturers can use to screen the hormonal influence of substances before these are launched on the market. Fortunately, the EU has now invested 50 million euros in eight projects that all concern better test methods for EDCs. Our goal is that in five years’ time, we will have many better tests that industry needs.' Legler is also the coordinator of the overarching cluster of these eight projects, the so-called "EURION" cluster, which has the aim of facilitating synergies between the projects. Many of the EDCs occur indoors too, states Legler. 'They bind to dust, and you breathe that in. A piece of simple advice is to ventilate rooms a lot and, in particular, to hoover a lot.'

Don’t you simply then ventilate these substances into your house again?

(Laughs) 'No, hoovering really does help! Besides food, dust in the home is one of the most important sources of EDCs. Hoovering is therefore very important. And for pregnant women, my advice is not to eat too much fatty fish, and certainly not more than is recommended. Research has already demonstrated that these type of substances accumulate in the fat of fish and may end up in the foetus. New research conducted by Hania Dusza, one of our PhDs, has shown that numerous chemicals with endocrine disrupting activity can be found in the amniotic fluid that surrounds the developing baby.'

Should we dispose of vacuum cleaner bags with the chemical waste in future?

'I do not do that myself, but perhaps we should. I assume that the Dutch waste incineration plants remove these substances with the latest technologies, but perhaps it is chemical waste after all. It is a good question and one I have not reflected on before. Everything comes together in ecology. This is why we need to stop endocrine disrupting chemicals at the front door, as otherwise, we will never get rid of them. We must all do our bit.'