When a climate physicist met an archaeologist…

What is the importance of a climate physicist in an archaeological study on a 18th century shipwreck? In this Utrecht Young Academy blog, dr. Erik van Sebille, oceanographer and climate scientist, discusses how interdisciplinary research is necessary to answer ‘big questions’.

“I love doing interdisciplinary research. Perhaps even more than monodisciplinary research. Whereas I often feel that my monodisciplinary projects make only tiny contributions to the circle of human knowledge, it is on the boundaries where disciplines meet that the big questions still lurk to be answered.

I am a climate physicist who explores how ocean currents move ‘stuff around’. I’ve worked extensively with geneticists to analyse marine ecosystems, with mathematicians to develop new methods for unravelling the network of ocean currents, and with ecotoxologists to map the harm of plastic on marine life. These were inspiring and fun interdisciplinary research collaborations that have led to dozens of super-relevant peer-reviewed articles. In each of these, the combination of expertise from two different disciplines led to new insights that wouldn’t have been possible in monodisciplinary projects.

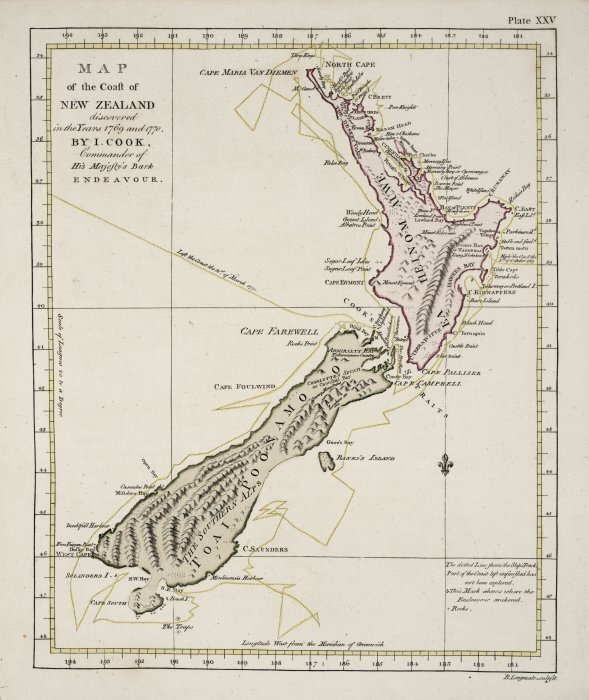

But there is one interdisciplinary study that I am particularly proud of: my collaboration with a group of archaeologists. That group, which I met through a colleague in Sydney, had just discovered the wreck of an old European ship on a remote beach in New Zealand. Carbon-dating showed that the wood used for the ship was harvested around 1705, making the ship much older than that of Captain James Cook’s when he was the ‘first European to explore New Zealand’ in 1769. And careful analysis of the wreck itself suggested it was Dutch; so that their find could potentially lead to rewriting the history books.

Many of the most interesting questions to be answered lie between disciplines but require state-of-the-art expertise from multiple of these disciplines.

There was only one big unknown: did the Dutch vessel actively sail to New Zealand? Or could it also have shipwrecked somewhere else (the Dutch sailed in the tropical Indian Ocean and the Indonesian Archipelago at the time) and drift to the New Zealand beach as a wreck? That is where I came in, with my knowledge on (past) oceanographic currents and flows. I used a special version of my plasticadrift.org website to calculate the most likely origins of wrecks that ended up on the New Zealand beach, and found that it was extremely unlikely (if not to say: impossible) for a wreck to have drifted there from the Indonesian Archipelago or tropical Indian Ocean. The conclusion was it must have actively sailed to New Zealand or at least wrecked relatively close by, pushing the first European exploration of New Zealand back by half a century or so.

During my physics degree I never had expected to be publishing in a journal on Archaeological Science.

I’m particularly proud of this specific project because during my physics degree I never had expected to be publishing in a journal on Archaeological Science. But more importantly, I feel that my contribution was a small (unlike my co-authors, I hadn’t spent years painstakingly excavating the wreck in a remote wilderness) but important piece of the puzzle.

And that is why I so much like doing interdisciplinary research. Because I feel I can help out others with their ‘big questions’. Many of the most interesting questions to be answered lie between disciplines but require state-of-the-art expertise from multiple of these disciplines. Collaboration is key then.

Interdisciplinary collaboration is not always easy. Others in this blog series have already spoken of the many pitfalls and challenges, as well as the opportunities, of interdisciplinary research. But I consider my interdisciplinary work as the cherries on the cake; the really fun projects that are opportunistic and that are hugely meaningful because they really drive science further. Plus, it has made me a lot of friends around the world.”

Erik van Sebille, PhD. Member of the Utrecht Young Academy. Associate Professor in oceanography and climate science.