Anna Maria van Schurman's role in cultural exchange with China more important than previously thought

The first female student at Utrecht University (and possibly in Europe), Anna Maria van Schurman, appears to have played a special role in the cultural exchange between the Netherlands and China. This is according to new research by art historian Thijs Weststeijn.

Anna Maria van Schurman was a pioneer

Dutch humanist, theologian and poet Anna Maria van Schurman (1607-1678) was the first female student of the Netherlands. In 1636, she was admitted to the newly founded University of Utrecht. She wrote mainly in Latin and was also a well-known calligrapher and artist in her time.

Thijs Weststeijn is Professor of Art History and interested in the earliest European responses to Chinese and Japanese calligraphy. A subject on which little is still known: “Some of the first demonstrations of this unique art form took place in the Netherlands: by Chinese visitors in Middelburg in 1601 and Amsterdam in 1654. In this context, I also came across Anna Maria van Schurman, who was already known for her qualities of calligraphy in various Asian languages such as Hebrew, Aramaic and Persian.”

Van Schurman was sent Japanese and Chinese texts to copy herself

Van Schurman focused particularly on languages that were important for biblical history, such as Hebrew and Ethiopian (Ge’ez). This generated so much admiration among her academic colleagues that apparently she was also expected to be able to copy other scriptures from East Asia by hand.

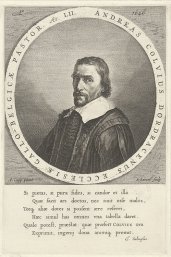

At Dutch universities, there was no one at that time who had mastered spoken or written Chinese. Weststeijn: “Her correspondence with the Reverend Andreas Colvius now shows that she was also sent texts in other scripts, including Chinese and Japanese, to copy ‘in her own hand’. Additionally, the correspondence refers to a so far unknown Chinese man who may have been living in Amsterdam since 1597 and could translate the texts for her.”

In my article, I argue that Anna Maria van Schurman was sent handwritten Chinese or Japanese calligraphy, to copy for herself.

Remarkable correspondence between Colvius and Van Schurman

Weststeijn examined the correspondence between Van Schurman and Colvius: “It is kept in Museum Martena in Franeker and there is a copy in the UU university library. Its existence was known, but not previously appreciated in the broader context of cultural exchange between the Netherlands and China.”

A Chinese printed text is kept in Museum Martena along with a letter to Van Schurman. “But that was probably only added afterwards” thinks Weststeijn. “In my article, I argue that she was sent not these but other texts, such as handwritten Chinese or Japanese calligraphy, to copy for herself.”

A richer image of the Dutch encounter with China

These new observations, Weststeijn believes, can once again add some richness to the picture of the early Dutch encounter with East Asia. “That porcelain in particular was collected in large quantities, we knew of course. But the cultural encounter had many more facets.”

“Dutch scholars, such as Isaac Vossius, had enormous admiration for Chinese civilisation, in a way that we do not see elsewhere in Europe. Now it turns out that Van Schurman, who had a huge network of friends and scholars and had a special reputation as an exceptionally literate woman, was also part of this exchange.”