A quarter of world's population facing extremely high water stress

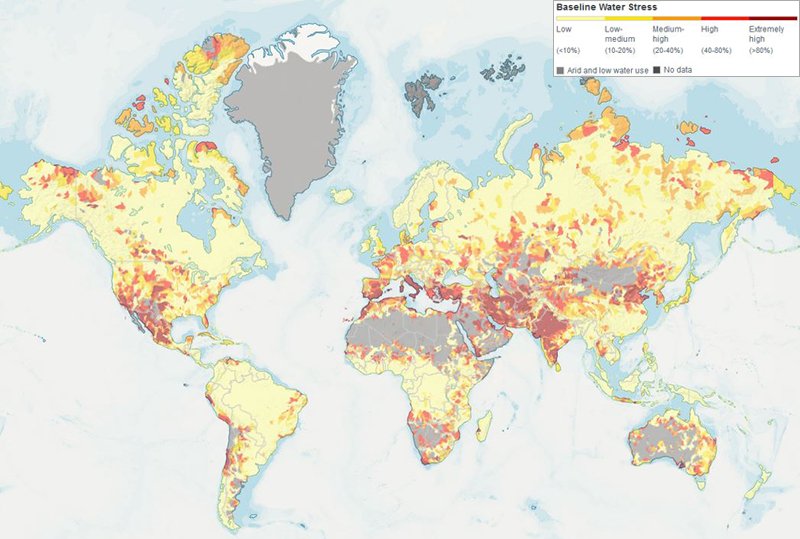

Extreme drought in countries including India and South Africa demonstrates how severe the impact of water scarcity can be. New research reveals that a quarter of the world's population is living in countries where water stress is extremely high. This research has been compiled in the World Resources Institute’s new Water Risk Atlas, which was published this week. Calculations by hydrologists from Utrecht University formed the basis for the atlas.

In countries with extremely high water stress, on average 80% of the available renewable water is used each year. This means that reserves are limited and the pressure on alternative sources such as groundwater is high. When the demand for water is great, even brief periods of drought can have major consequences. Such periods increase the risk of acute water stress as seen in Cape Town, South Africa in 2018 and currently in Chennai, India. The new calculations reveal that this risk is extremely high for seventeen countries, which are together home to one-fourth of the global population.

Serious threat

A shortage of water poses a serious threat to people, animals and nature. It can yield serious repercussions for food security and may cause or exacerbate conflict and migration. And as a result of climate change and a growing global population, water stress will only continue to increase in future.

Hydrological model as a basis

The global hydrological model designed by the hydrologists in Utrecht – known as the PCR-GLOBWB model – serves as the basis for the indicators in the atlas, which offer insight into the current and future status of water sources and their usage. Using the model, the scientists were able to calculate the water demand, availability of surface and groundwater and the resulting water depletion for individual 10x10 km ‘cells’ of the earth's surface.

Preventing ecological damage

Because all data is now available at a uniform resolution and has been calculated using the same model, the various indicators of water stress can now be compared. This reveals not only where the pressure on renewable sources of water is great, but also where the limits of sustainable consumption have already been exceeded and groundwater stores are becoming depleted. Such situations exist in regions like the Middle East and North Africa, where the current scarcity is expected to become more dire in future. ‘We must seek more sustainable solutions in these regions, to prevent further ecological damage and to offer people sufficient long-term social security,’ says hydrologist Dr Rens van Beek, one of the Utrecht-based hydrologists who together with Prof Marc Bierkens, Dr Yoshihide Wada and Dr Edwin Sutanudjaja made up the Utrecht atlas team.

Their hydrological model previously enabled the team to visualise flood risks worldwide and set limits for pumping groundwater.

Research partners

The Utrecht hydrologists developed the data for the World Risk Atlas as research partners of the World Resources Institute, together with colleagues from Delft University of Technology, Deltares, the Institute for Environmental Studies (IVM), PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency and RepRisk.