Solving more mysteries

The evolution of equine motion analysis

The ancient Egyptians already wondered whether a trotting horse ever lifted all its hooves off the ground at any given moment. While we now know that such a 'hovering moment' does indeed occur, this could not be visually confirmed at the time due to the horse's high speed. Our fascination with animal movement is an age-old phenomenon. For example, Aristotle wrote De Motu Animalium, a text on animal locomotion, hundreds of years before Christ. The Greek philosopher's fascination is still shared by scientists today, including our researchers at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine. The biggest difference: Aristotle and the ancient Egyptians had to rely on their visual observations, whereas animals move much faster than the eye can see. These days, modern technology is helping the faculty to gather an unprecedented amount of knowledge on equine locomotion.

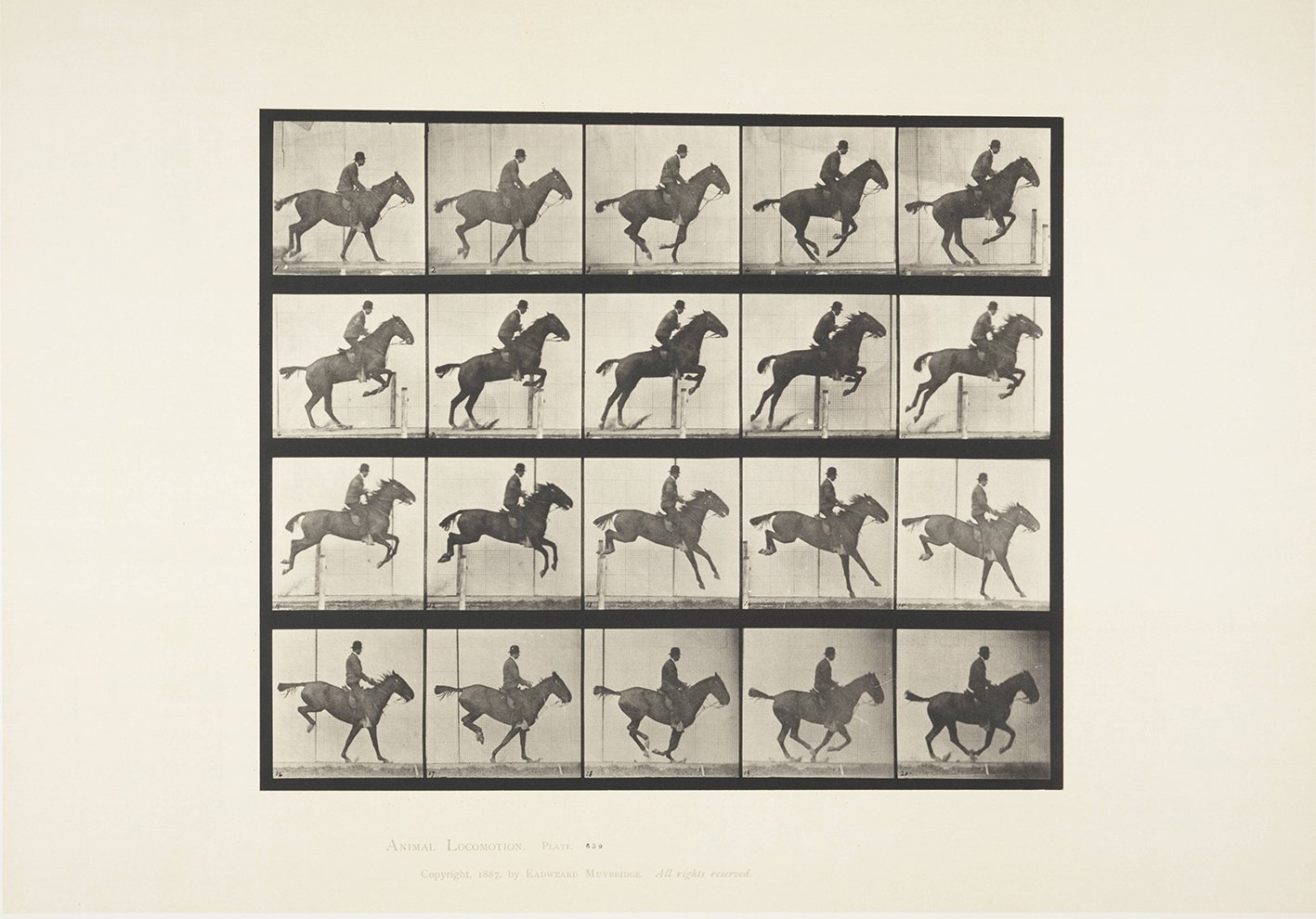

First, though, let's travel back in time for a moment. The advent of photography greatly advanced our understanding of equine locomotion, as René van Weeren of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine explains: 'American Leland Stanford lived in the nineteenth century and was driven by the same curiosity as the ancient Egyptians thousands of years prior. The railway tycoon wanted to find out whether his trotting horses ever lifted all their hooves off the ground at the same time. He joined forces with British photographer Eadweard Muybridge, a pioneer in the field of photography. In 1878, Muybridge photographed various horse gaits using a battery of twelve cameras. As it turned out, the horses briefly 'floated in the air' during both a regular trot and gallop. He had solved the mystery that first perplexed the ancient Egyptians.'

The serial number was 007

This movement would have to be visualised if we aimed to learn more about equine locomotion – that much was clear. Researchers at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine attempted to tackle this challenge in the 1980s. They ordered a state-of-the-art opto-electronic measuring device known as CODA-3, which was designed to determine the three-dimensional coordinates of markers. Van Weeren still remembers enthusiastically unpacking the device upon arrival in Utrecht, only to discover that it bore the serial number 007. 'We felt that was very apt, somehow. Still, using it on horses proved more challenging than we'd initially expected. The device emitted light that was then reflected by markers on the horse. However, the – expensive – markers never seemed to stay in place and the system was also poorly suited to horses in other respects. It took several years of thorough rebuilding before it could be used to measure equine movement for the first time.'

Treadmill

'007' has long been a museum piece, and the Equine department now has far more effective ways of studying equine locomotion. For example, the department uses a system comprised of 18 cameras and markers glued – firmly – to the horse. Researchers also have access to another less costly stand-alone system that relies on sensors attached to the horse and can be used in any environment. In recent years, motion analysis systems have evolved to the point where they can now be used in clinical settings. This has speeded things up considerably. These advances in motion analysis offer huge benefits for horse owners. Veterinarian Johan Oosterloo of Wellensiek Veterinary Clinic in Nijkerk: 'If lameness is diagnosed at a late stage, the injury will have become more serious by the time it's detected. I can now use motion analysis to diagnose the problem before it gets worse. There have been a lot of technological advances during my twenty years as a veterinarian. While the vet's keen eye – in combination with the owner's input – remains the most important tool we have, new developments in motion analysis can certainly help us detect things we can't see with the naked eye.

Developments in the field of Artificial Intelligence are especially promising

Analyses can be carried out in the arena or – a new development – on a special treadmill for horses. The treadmill at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine can go reasonably fast (up to a maximum speed of fifty kilometres per hour) and has an incline feature to increase the workload. The faculty was also among the first to use a force plate – a platform designed to measure the forces exerted by motion – in the 1980s. After all, motion analysis measures two main variables: the actual movement itself and the forces it exerts on the surface. The latter factor also yields important clinical data, as it is indicative of the strain put on the horse.

At the Hartog Talentendag 2021 organised by the Royal Dutch Equestrian Sports Federation (KNHS), the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine demonstrated its motion analysis systems with the help of EMG and EquiMoves. This allowed talented riders to acquaint themselves with the latest in motion analysis technology for their horses that also measures their muscle strength.

Artificial Intelligence

Real-time insight Thanks to modern technology, we can now largely solve the mystery that once baffled ancient Egyptians. However, there are still some challenges ahead, as Van Weeren explains. 'We can clearly see what happens when a horse moves these days, but we still need to interpret those movements correctly,' he explains The Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and various researchers around the world are currently developing systems for that very purpose. EquiMoves is the latest of these systems, and is being developed by the faculty in collaboration with the University of Twente. Meanwhile, French researchers are developing a specialised horseshoe that measures soil reaction forces. Researchers are also working to integrate EMG systems in order to allow for more accurate muscle activity measurements; after all, muscles generate the force needed to initiate movement'. Developments in the field of artificial intelligence (pattern recognition by computers) are particularly promising in this regard. We are gradually solving more and more mysteries. The ancient Egyptians would have loved to be around now.