Ready for the rising water

The largest evacuation ever in the Netherlands due to flood risk is 25 years ago this winter. 250,000 people had to leave their homes in river areas due to the dangerous high water levels of the Rhine, Maas and Waal. Several water researchers at Utrecht University have personal memories of this. They reminisce on those days and look into the future. Are we ready for more rising water?

“Extremely hectic days, you can hardly imagine it now without cell phones and the internet, the most modern means of communication being the fax machine”, says Herman Havekes, Professor by Special Appointment: Public organisation of (decentralised) water management at Utrecht University. On January 31, the waterolevel at Lobith reached a record height of 16.63 meters above sea level. Back than, Havekes worked (and is still working) at the Dutch Union of regional Water Authorities.

Deployment of soldiers during flood risks in 1995

“Sometimes I long for those days because a huge amount of work could be done in a relatively short time. The Delta Act on major rivers - an emergency law that wasn't allowed to be called an emergency law - was adopted by the Dutch parliament (Lower and Upper House) within a matter of weeks. A lot of money was earmarked for reinforcement of dikes and other water safety measures. Procedures got accelerated.”

Climate refugees - avant la lettre

Everyone living close to the rivers was biting their nails, in 1995. Under the eyes of many reporters and cameras, hundreds of soldiers were deployed at Ochten, at the river Waal to reinforce the dyke with sandbags. Soldiers also helped with evacuation of climate refugees avant la lettre. In large parts of the area's around big rivers hundreds of thousands of people and many cattle had to leave their homes. Children were sent to schools in other villages.

“I remember the extraordinary side effects”, says Havekes. “A picture of a windsurfer on the inundated A2 highway near Den Bosch became world news. At the owners of dyke houses, often Amsterdam art painters only living there during summer and protesting dyke reinforcement, the windows were smashed by angry people. A provincial legislator in the province of Gelderland almost had to resign because he dared to publicly doubt the ability of the water authorities to deal with the situation.”

Frank Groothuijse, associate professor of Environmental law at Utrecht University reminisces: "I was child, going to school in den Bosch in those days, and I remember the agited atmosphere surrounding the water levels. For public awareness it is good if it almost goes wrong, every now and then. It leverages political support and financial resources for water safety. The prayer of the Dutch dijkgraaf (the chair of a Dutch water board.) is often jokingly phrased as: "Give us this day our daily bread and every now and then a flood.” (in Dutch the word bread: brood, rhymes with flood: watersnood).

Herman Kasper Gilissen was a young kid, going to school in Arnhem. He remembers that he and a friend were being naughty and cycled on the quay of the Rhine. They ended up getting wet almost as high as their armpits. "I lived in an area where we often drove over a narrow dyke. I remember sitting in the car with my mother, both looking out of the car windows, deeply impressed by how high the water was at that time. I think thats when my fascination with water management started, leading me to specialise in water law.” Gilissen is currently a teacher and a researcher at Utrecht University's Center for Oceans, Water and Sustainability Law.

When I think back on the near floodings of 1995, I think that's where my fascination with water management started

The near disaster of 1995 drastically revised our thinking

The Netherlands was holding its breath in 1995. Fortunately, the dikes abided. The near-flooding led to a drastic change in thinking about safety along the rivers. With the programme Ruimte voor de Rivier (space for the river), the area surrounding the large riviers in the Netherlands was transformed. Ruimte voor de Rivier has been evaluated by Utrecht University on its governance an legal aspects with many positive findings. One of its successes was its attention to the natural beauty and quality of the landscape in the river area. Maintaining that was one it's objectives as well. As a result, the regions affected, also had an interest in the adjustments and resistance to the programme was relatively low.

Havekes: "“What we can learn from 1995 is that the "water wolf" as we call it in the Netherlands is not to be mocked. There must be sufficient resources for water safety. The amount is very reasonable. The Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management has done the research and concluded that water safety has cost the Dutch citizens 35 euro per person per year, since 1953.”

Water safety has cost us around 35 euros per person per year since 1953, that's reasonable, right?

Utrecht University has a leading position in the field of water law. Marleen van Rijswick, professor of European and national water law, is programme leader of the Utrecht Center for Oceans, Water and Sustainability Law and at forefront many progressive research projects. She and her team have a long tradition in the Netherlands and work together with colleagues from all over the world. Researchers have a long standing tradition of working in the Netherlands and also collaborate closely with colleagues from all over the world. They are involved in exploring new approaches to water safety through research and consultancy to governments and other organisations. Take for instance the project ALLRISK , supporting the Dutch national Hoogwaterbeschermingsprogramma (High water protection programme) with scientific research. Before that, they were involved in the EU project STARFLOOD, on dealing with flood risks in urban areas near rivers. "We explored various policy options there. What do you choose as a strategy in the event of a (imminent) flood and how do governments and private partners work together?", Herman Kasper Gilissen explains. He worked in STARFLOOD.

"You can reinforce dikes, but you can, for example, also decide not to live in risk areas anymore. Stop building there and use the land differently. Or allow an area to partially flood and secure its buildings with bulkheads and high thresholds. Another strategy is becoming experts in evacuation, and to practice that more often. Also important regarding your stragety is to make plans for what you want do with the flooded area after the water damag. Do you rebuild it as before? Or not? Other countries - France for example - are more experienced in those strategies than the Netherlands. "

Letting go of parts of the Netherlands

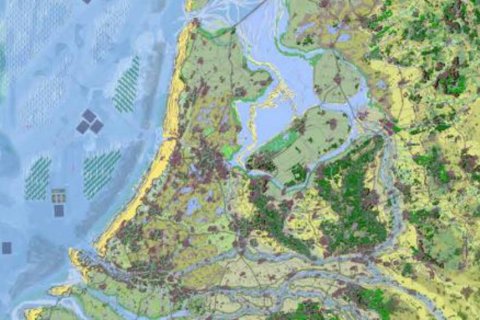

His colleague Groothuijse agrees with him. "The question is whether we can continue to fight the rising water in the same way we've been doing it in the past, in the next century. Or wheter we should give up parts of land in the Netherlands, due to climate change, sea level rise and land subsidence. Look for expamle to the recent scenario's of the map of the Netherlands by Wageningen University & Research."

The question is whether we should give up parts of land in the Netherlands in the coming century.

With the current Safelanding-research proposal, Utrecht University, together with other universities, wants to explore the real world implications of future scenarios for the Netherlands. Which policy optionsdo we have today, that help us in the long term? Who is responsible for what? "

Professor by Special Appointment Havekes is pretty confident regarding the future: “The new water safety norms (in effect since January 2017) are a step towards in the further development of water safety policy. We have the idea that we have now (finally) learned our lesson: there is enough money and a clear allocation key, procedures have been optimised. Within the Dutch Hoogwaterbeschermingsprogramma (high water protection programme) there is strong collaboration on all levels of government. And in the Deltacommissaris (Delta Commissioner) we have a powerful official and watchdog who can ring the alarm when needed, a figure with political authority. "