Higher dykes will not protect us from the water

At the climate summit in Katowice in Poland, the signatory nations to the Paris climate agreement have tried to reach agreement on concrete measures. Yet the Netherlands is still doing very little to reduce CO2 emissions. Relatively speaking, we generate far more than the global average and have barely reduced emissions in the past few decades. The time has come for us, and other rich nations, to take the lead, quickly and decisively. The Dutch, more than most, need to find an answer to rising sea levels. You sometimes hear claims that climate change is “disputed”, but they are simply wrong. The sea level is rising – the only question is how fast.

This op-ed appeared in the Dutch newspaper NRC on 6 December.

By: Prof Maarten Kleinhans, Prof Appy Sluijs, Dr Patrick Witte, Prof Marleen van Rijswick, Dr Herman Kasper Gilissen, Prof Steven de Jong, Prof Gerben Ruessink, Prof Hans Middelkoop.

Why are higher dykes and building another flood barrier at Rotterdam not enough to save us? Dutch history resonates with tales of floods and of engineering solutions to overcome them. Many of these disasters reveal a remarkably similar pattern: people drained low-lying wetlands for agriculture and habitation and protected them with dykes. But lowering the groundwater level causes soil subsidence, and dykes prevent the natural influx of sludge that would compensate for this effect. All the new polders are in fact waiting for the final drop of water to make the bucket overflow. Examples include the Saint Elizabeth’s Day flood of 1421, the North Sea flood of 1953 or, further afield, the New Orleans flood following hurricane Katrina.

Whereas the disaster of 1421 affected only a dozen or so villages, today the entire Randstad conurbation is one huge polder of much the same kind, home to some 10 million people and the economic heart of the Netherlands. Worldwide, half a billion people are living in similar flood-prone river deltas. And the threat no longer comes from occasional bouts of extreme weather, but from unprecedented lasting changes in climate and sea levels.

When sea levels rise substantially, salt water will creep under the raised dykes. This causes problems for drinking water supply, agriculture and nature. Larger dykes are expensive, but still fail to stop the seepage below. Eight thousand years ago, when the sea level last rose as quickly as is predicted for the twenty-first century, there was already too little sand and silt in the Rhine delta to prevent half of what is now the Netherlands from drowning.

Even if we achieve the targets set in the Paris climate agreement, there will still be more greenhouse gases in the atmosphere than before the industrial era, with levels continuing to increase, so the climate will change anyhow. The result: sea levels may “only” rise by a few metres. For large parts of the country, this threat could be overcome by depositing large quantities of sand along the coast, reinforcing dykes and, above all, allowing the natural silting of areas situated at too low a level – but where housing developments are still being built. Such major land use transformations are hard to bring about, but all the signs indicate that we have to make a choice for solutions that would not preclude future adjustments.

First of all, we need to reduce CO2 emissions to zero, in the Netherlands as well as in the rest of the world. But we also have to make changes to the landscape and its management. So rather than encapsulate the subsiding land in high dykes and dunes, pump out the salty seepage water and river water using powerful pumping stations. And introduce controlled flooding from sea arms to create natural silting in critically low-lying areas. Past examples show this could actually work. One such example is the “drowned land” of Saeftinghe in the province of Zeeland, which is now several metres higher than the countryside behind the nearby dykes. Moreover, such zones would help reduce extreme high water and create healthier ecosystems. They are also essential for the salt-crop farming, fishing and aquaculture we are going to need in the future.

Rather than encapsulate the subsiding land in high dykes and dunes, pump out the salty seepage water and river water using powerful pumping stations, we should introduce controlled flooding from sea arms to create natural silting in critically low-lying areas.

Most of the Dutch population now live and work in the Randstad, the country’s lowest-lying region with the weakest soil. The central government, provincial and local authorities and regional water boards recently agreed to create more green zones in urban areas, as well as larger water catchments. However, these measures are supposed to address climate change by limiting the impact of extreme heat and rainfall, and actually divert attention away from the inevitable rise in sea levels.

If we really want this “let’s-get-to-work” agreement, as Minister of Infrastructure and Water Management Cora Van Nieuwenhuizen calls it, to achieve something, then ordinary people and the business community will have to be engaged more in climate policy. Are we sufficiently aware of the risks of doing too little? Here in the Netherlands, there is widespread public confidence that the government will protect us from water – and rightly so. But all of us also need to know where it is better not to live, before homes and businesses are declared uninsurable due to subsidence and the risk of flooding.

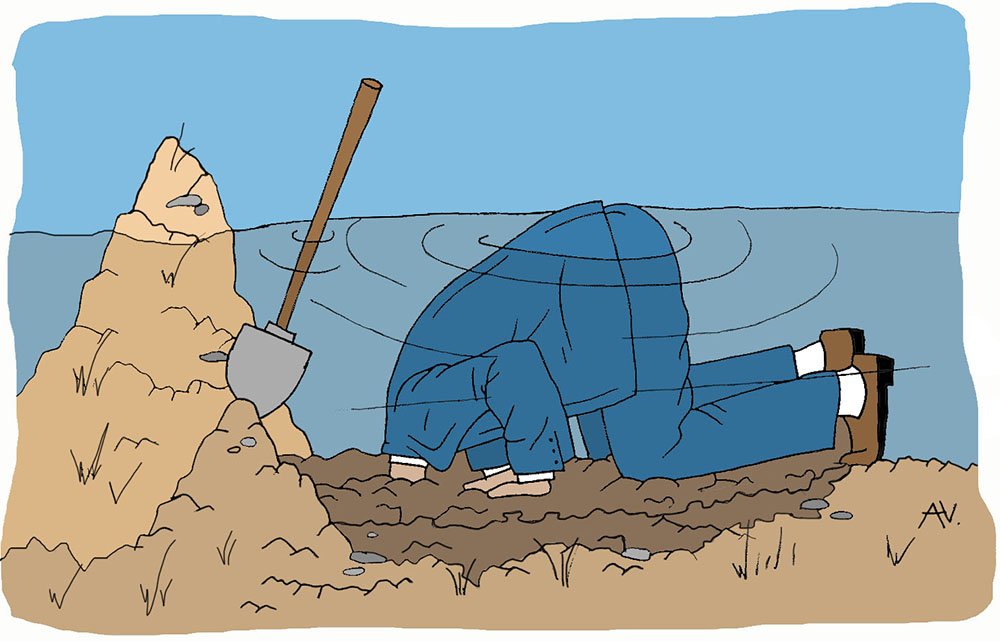

The Delta Commissioner was right when stating recently that we still have enough time to introduce fundamental changes in the areas of housing, agriculture, fresh-water supply and their spatial planning. Achieving “Paris” also opens up new opportunities for innovation, which will keep our nation an attractive place to invest in the long term. But for that we to have to develop a vision for the Netherlands of the near future, and quickly. Anyone who sticks their head in the sand now is very soon going to be pulling it out of the water.