Less plastic in the ocean and easier to clean up

Relatively many large, floating pieces

Significantly less plastic is estimated to be present in the global ocean than scientists previously thought. This new insight results from calculations with a computer model that includes a record number of measurements and observations of plastic in the ocean. Also, a relatively large proportion of the plastic in the ocean consists of large pieces that are easier to clean up. The study is part of Mikael Kaandorp's doctoral research at Utrecht University and appeared in the scientific journal Nature Geoscience today.

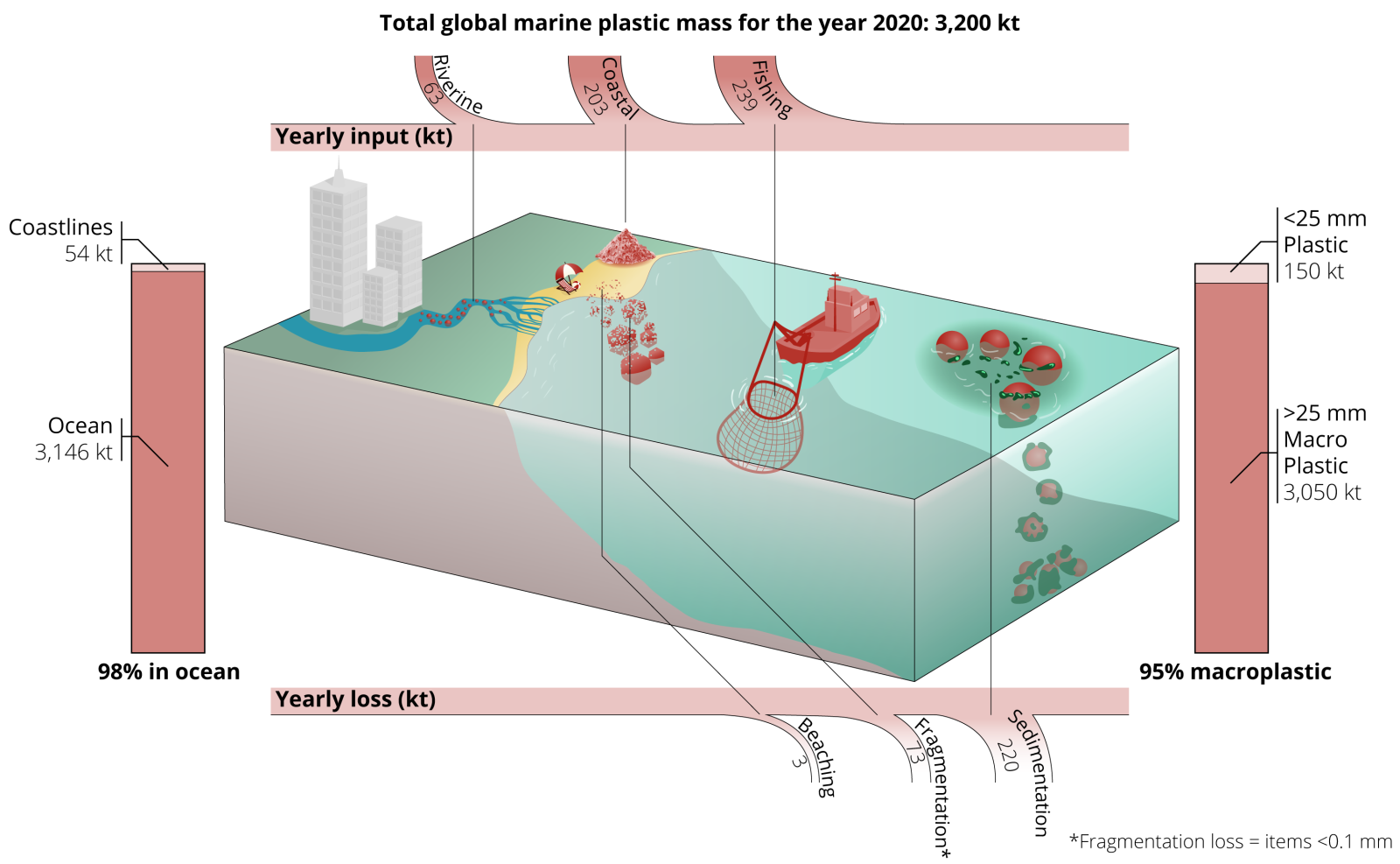

To date, the total amount of plastic in the ocean has been estimated at more than 25 million tons. This figure is derived from the assumption that 1 percent of the total amount of plastic in the ocean floats on the ocean surface, which is estimated to be a quarter of a million tons. The new study shows that the amount of plastic on the ocean surface is much higher, at about 2 million tons, but only one million tons is present in the deeper ocean (this excludes the amount of plastic on the bottom of the ocean). Thus, the total amount of plastic in the ocean is much lower, and the proportion floating on the surface relatively large.

Infancy

Moreover, much less new plastic ends up in the ocean per year than previously believed: half a million tons instead of 4 to 12 million. The numbers show enormous differences. According to lead author Mikael Kaandorp, this shows that research on plastic in the ocean is in its infancy. "We are really still looking for order of magnitude," he says.

Text continues below

Decades in the ocean

So, while most plastic particles in the ocean are very small, the total mass of those microplastics is relatively small. A surprising finding given the expectations, says Erik van Sebille, Kaandorp's PhD supervisor. And good news. "Large, floating pieces on the surface are easier to clean up than microplastics." Incidentally, the study also shows that about half of those large pieces come from fishing boats.

Another important conclusion drawn by the researchers is that plastic remains in the ocean much longer than thought, roughly decades. After all, much less plastic ends up in the ocean per year than thought, but the amount floating on the surface is much larger. And that, according to Kaandorp, is bad news: "It means that it will take much longer until the effects of measures to combat plastic waste will be visible. It will be even more difficult to get back to the situation as it once was. Also, if we don't take action now, the effects will be felt for much longer."

Until now, scientists have mainly looked at measurements of quantities of plastic in the upper layer of the water surface

Complex computer model

The new predictions about the amounts of plastic in the ocean were made with a computer model. Kaandorp fed the model with measurements and observations of amounts of plastic in the ocean. Then the model derived the total amount of plastic from that. It used a diverse array of variables, including the rate at which plastic washes ashore, breaks up into smaller pieces, and becomes covered in algae, making it heavier and sink to the bottom.

Record amount of data

Previous estimates of quantities of plastic have also been made with computer models. This model stands out because of the record number of measurements and observations included. "Therefore, this model is more accurate," Kaandorp says. "Until now, scientists were mainly looking at measurements of amounts of plastic in the upper layer of the water surface. We added counts of beach cleanups in various places around the world, and observations of large floating plastic objects on the water, among other things. Those pieces are relatively scarce, but because they are heavy, they make up a large portion of the total amount of plastic in the ocean."

The study is the culmination of the Topios project in which researchers spent five years investigating how plastic moves through the ocean.