Campus Living Labs test new, transformative ways of thinking and doing

Achieving a sustainable and just future for all will require new and innovative ways of thinking or doing across society. But for these ideas and solutions to become the norm, we first need to test and experiment with them on a smaller scale, learning what it is that makes them successful. One way to do this is through so-called living labs.

In its Strategic Plan up to 2025, Utrecht University aims to be a living lab pioneer, where researchers, students, operational staff and societal partners together co-create and experiment with solutions to complex sustainability challenges on campus.

To learn more about the research behind living labs and how Utrecht University is engaging with them, we talked to two PhD researchers from the Copernicus Institute of Sustainable Development: Harm van den Heiligenberg and Claudia Stuckrath Alvarado. Van den Heiligenberg’s research has provided a scientific basis to help us understand the conditions needed to make living labs for sustainability successful in urban areas. Stuckrath Alvarado is now zooming in to see how these hotbeds for experimentation can be used to bridge campus operations with academia, accelerating the transformation to a sustainable society.

Firstly, what are living labs, and why are they an important way of finding and implementing solutions to societal challenges?

Van den Heiligenberg: An enormous glacier in Antarctica is about to collapse, the bee population is decreasing dramatically, and the growing season of plants is shifting. These alarming signals are coming closer into our daily lives and are a sign of a much larger underlying sustainability problem. We are approaching the biophysical limits of the Earth system, and need fundamental changes to our energy, food and transport systems to name a few.

Transition theory suggests that this fundamental change starts small, in practice-based experiments with innovations in their local context. Living labs are spaces where technological or social innovations can be tested in real-life, with a lot of user or citizen involvement. Bringing together new constellations of actors in a real-life setting helps us get the insights we need to scale-up these innovations to other districts, cities, and regions.

Living labs are spaces where technological or social innovations can be tested in real-life, with a lot of user or citizen involvement

Can you give an example of a living lab?

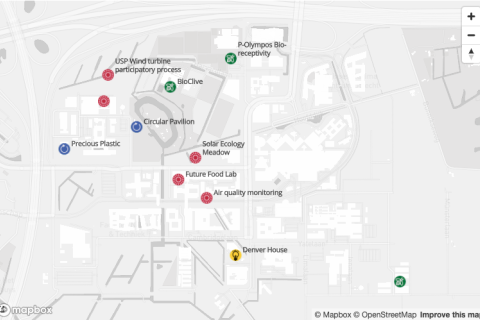

Van den Heiligenberg: Denver House is a living lab here in Utrecht Science Park in the field of sustainable living. Built by students from the Utrecht University of Applied Sciences, here students, researchers, and partners from the business community can try out new energy and circular innovations together. It provides a unique opportunity to test building components, products, and materials under real-life conditions.

What conditions help make innovations break out into the mainstream, according to your research?

Van den Heiligenberg: A very important issue for these pioneers is how to become successful—that these innovations scale up and spread out to other parts of the world. In our research we analyzed the contexts enabling this scaling-up process. We found that areas with a combination of a strong countercultural milieu, local and regional networks with a culture of openness and trust, a vibrant environment with conferences and festivals, and support from the government and the university creates a good ‘habitat’ for this kind of experimentation.

Do certain districts, cities, or regions offer better conditions for experimentation than others?

Van den Heiligenberg: In our research we searched for the so-called frontrunner regions in Europe; regions that offer a beneficial context for experimentation and scaling-up and can act as inspiring examples for others. Preliminary results show these are mainly found in Northern and Western Europe, but also in other parts of Europe, such as Budapest and Catalunya. The province of Utrecht scores also quite well!

Aside from my PhD work, my main work is as a policy advisor at Utrecht Province. We are using the insights from my and other transitions research to try to improve the upscaling potential of living labs in the region and contribute to long-term Dutch and European sustainability and health goals. We even discussed this topic recently with experts from the European Commission!

Claudia, Utrecht University campus is becoming a hub buzzing with living labs. Why is a campus an ideal place for these hotbeds of experimentation?

Stuckrath Alvarado: In general, universities are where knowledge is created and innovation occurs. This makes the campus an ideal place to foster experimentation in a real-life setting. There is a huge potential that is being wasted in our university. On the one hand, there is top-notch knowledge being created by academics. On the other hand, the university's operations have the ambition to be more sustainable, but they don't have the know-how. Utrecht University Living Labs—also known as UULabs—aims to provide a framework to bridge these two spatially close but different worlds.

How does your research fit in here?

Stuckrath Alvarado: My PhD research is looking at how living labs can be best implemented on campus to foster sustainable operations—a key aim of the university’s Strategic Plan 2025. For these living labs to be successful, they should be autopoietic—capable of producing and maintaining themselves by creating their own parts. I’m looking at how a bio-inspired lens can help us design and implement such a lab. The idea is to use the literal meaning of “living” to foster experiments that are not only in “live” scenarios but are also “alive”.

My PhD research is looking at how living labs can be best implemented on campus to foster sustainable operations—a key aim of the university’s Strategic Plan 2025

What could you learn from Harm’s research?

Stuckrath Alvarado: Harm’s research is very interesting. Each living lab is different in many ways, and the habitat they are in is a key factor in its success. Understanding how this works helps us create a flourishing habitat for living labs on the campus. Curiously, Harm used a term from nature, "habitat", to describe the context where living labs flourish. It is still too soon to tell from my research, but this could be a sign that living labs have characteristics of living organisms.

What kind of activities are going on campus right now and what can we learn from them?

Stuckrath Alvarado: In addition to Denver House, which Harm has already talked about, we are working on several projects. The renovation of the Van Unnik building, the iconic 1960s highrise in the middle of the campus, has the ambition to be circular and regenerative, with a living lab involving solar energy, ecosystem services, bio-based materials, and behavioural psychology. Another project is the Solar Ecology Meadow, a place where renewable electricity can be generated while increasing biodiversity. And recently, we initiated the first steps of setting up a Circular Clothing Living Lab!

How do campus living labs help the transition to sustainability in wider society?

Stuckrath Alvarado: The theoretical idea is that we can showcase potentially transformative practices to society. By creating, supporting and actively communicating about living labs our efforts will become well-known to a wider audience. Also, a place where you can experiment with innovative ideas in a safe environment helps reduce uncertainties and speed up transitions. It does require a mindset change though because unwanted results are still perceived as failures. The whole idea of experimenting is that you are doing it because nobody knows how to achieve the desired result. The experiment helps you on your way, mobilising people and their ideas to discover what works and what doesn’t.

About the researchers

Claudia Stuckrath is a PhD candidate and consultant in innovation for sustainable development with a focus on circular economy. She is a civil engineer with Masters in Biobased Materials and in Sustainable Business and Innovation. She has worked at the intersection of academia and industry for more than eight years, transforming research into applied industry innovations. Her passion for multi- and interdisciplinary projects has led Claudia to work in Living Labs to accelerate the transformation of Utrecht University towards sustainable development.

Harm van den Heiligenberg is a PhD candidate; he studies the success factors of sustainability experiments in their geographical context. He is especially interested in living labs in Europe. Theoretically he aims to contribute to the emerging field of the geography of transitions. He combines his research with his work as a policy advisor at the Province of Utrecht, in the field of innovation and sustainability. In the past he was a senior researcher at the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency (Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving), where he was the project manager of the first Sustainability Outlook of The Netherlands.