'Journael van ’t gepasseerde op mijne reijse in Engelant' by Abraham Booth

A Booth abroad: the travel journals of Abraham Booth

In 1629 Abraham Booth, a young agent working for the Dutch East India Company (VOC), was sent to London as secretary to a delegation of company officials and Dutch ambassadors with the intention of setting about the release of three captured merchant ships. While there, Booth kept a detailed personal journal of his activities, which included equal amounts of work and play, as he frequently embarked on short and long trips around the country. Although he mostly remained in the vicinity of the capital, he also took part in several more extensive outings, including a tour around Cornwall. His journal, which survives in multiple parts, provides a unique insight into the way early modern England and its lively capital were experienced by a visitor from the Low Countries.

Early years and first embassy

Born in Utrecht in 1606, Abraham was the second son of minister Everard Booth and Alid Ruysch. He had a sister, Henrica, and an older brother, Cornelis, who would become Utrecht University’s first librarian. Both of his parents passed away before he turned eleven, leaving only his uncle, Adriaen Booth, to look after him and his siblings. Little is known of his upbringing. He likely received some formal schooling while growing up, but there are no records of him attending university. In 1627 he joined the Dutch delegation sent to negotiate peace between Sweden and Poland as deputy to secretary N. Schultsen. As recognition for his efforts during the embassy he received a commemorative medal from the Swedish king, Gustavus Adolphus. He returned to the Low Countries in 1628.

Journey to England

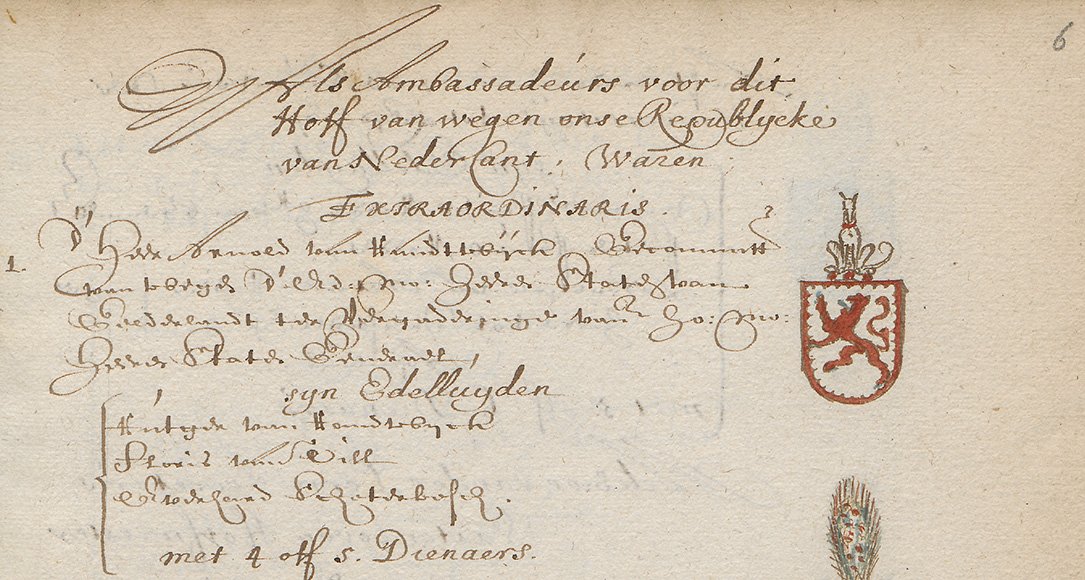

These experiences may have whetted Booth’s appetite for traveling, because he did not remain at home for long. Less than a year after his return he was sent to England with a group of VOC officials as secretary to the Dutch ambassador there, Albert Joachimi. The reason for this diplomatic mission was the 1623 Amboyna Massacre, an event that today would certainly be called an international incident. That year, the captain of the VOC trading factory on Ambon Island (Moluccas, Indonesia) heard rumors that the English were planning to take over control of the island by bribing Japanese mercenaries hired by the Dutch. Quick to prevent any treachery, he responded by arresting several Englishmen and some of the Japanese. Confessions were extracted by torture and twenty men were executed, including the English captain, Gabriel Towerson. Only a few were spared to spread word of what had happened. Needless to say, this did not sit well with the English, who demanded retribution. The VOC insisted their actions were justified, and as a result diplomatic relations between the countries cooled considerably. After years of negotiations, the English were hoping to enforce their claims by capturing three VOC vessels on their way home from the East. Joachimi’s delegation, including the young Booth, was not only sent to London to bring about the quick release of these ships, but also to try and put the Amboyna matter to rest.

Booth’s journal

The journal survives today in two parts, one of which is kept in the National Library of the Netherlands in The Hague (131 H 30), the other in the Utrecht University Library (Ms. 1197). The first comprises the majority of his stay in England, while the latter contains the second half of his travels around Cornwall and his journey back home to the United Provinces. His stay abroad lasted from February 1629 to June 1630, with a brief return back home from June to July 1629. He likely wrote the entries in his journal during his time in England, and later collected and copied them to create a single version written in a neat hand. Sadly, this edition was never finished, abruptly ending during a stopover in Andover on the way to Salisbury. The neat copy, which contains several illustrations, is also kept in the Utrecht University Library (Ms. 1196). Together with the second half of his original notes (Ms. 1197) it contains the complete narrative of his time in England.

Despite the serious nature of the diplomatic mission, Booth appeared to have had plenty of free time on his hands. In fact, he rarely wrote about matters concerning the negotiations, only taking care to keep account of which English dignitaries came to visit the Dutch, and vice versa. The rest of his journal was reserved for noting the many wonderful things he saw or experienced while in the country, some of which are introduced below.

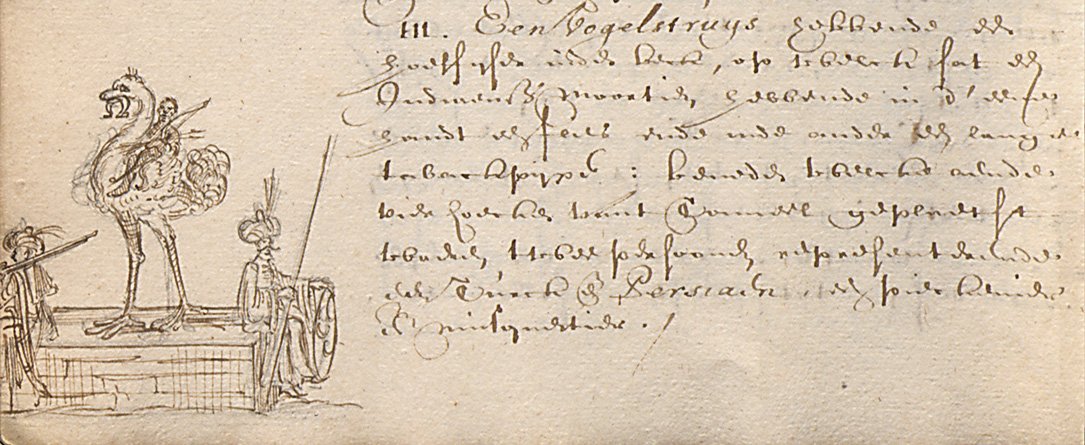

The Lord Mayor’s Show

As part of a prominent deputation, Booth had the good fortune to be a spectator to many notable events and festivities during his time in London. Perhaps the most grandiose of all was the Lord Mayor’s Show, which he attended on 8 November 1629. This event celebrated the election of a new Lord Mayor for the City of London by means of a grand parade. It is still held each year today. In his journal Booth included detailed descriptions of the parade’s floats, each of which represented a specific scene and often contained allegorical messages. The text is accompanied by a few drawings that were first sketched with pencil and later drawn over with ink. These sketches, although small and somewhat crude, form a valuable source of information about the show from someone who experienced the parade first-hand. After the show, Joachimi’s party was invited to join a grand banquet, where Booth remarks that the diners consumed so much food that they were sure to die from overeating.

Lions, leopards, and lots of weapons

Booth also visited a certain castle in the city that remains a popular tourist destination even today: the Tower of London. In the early-17th century it was still very much in use, mostly as a prison – which would be the case until as late as 1952 – but also as a fortified castle. Booth was clearly impressed by the building, as he took the effort to describe almost every room he went through during his visit, something he rarely does elsewhere. The first section he saw was known as the Lion Tower, since many exotic animals were kept there as part of the Royal Menagerie. Booth recalled seeing lions, leopards, a wolf, a civet cat, and ‘many other strange and to us unfamiliar beasts’ (ende meer andere rare ende voor ons onbekende beesten, Ms. 1196, fol. 19v). Unfortunately, or for the animals perhaps fortunately, the Lion Tower no longer exists. Booth’s tour also led him through a variety of rooms and halls that were filled to the brim with all sorts of weaponry, ranging from antique spears to halberds, rifles, and more. In his reckoning, the stores in the castle could be used to arm upwards of 60,000 men!

Endless rain in the capital

Despite all of London’s charms, there were some aspects of life in the city that seemed to appeal less to Booth. Most notable of all was the excessive amount of water, mostly in the form of rain. He wrote that on 26 June 1629 an important diplomat from Savoy, France, drowned when he fell into the water below London Bridge. Later the same year, in October, two men drowned in the city’s gutters as a result of heavy floods. Clearly the weather could be perilous even within the confines of the capital. Booth himself was merely inconvenienced by the torrential outbursts: he recalls that on the same evening he ‘came home like a drowned cat’ (ende quam als een verdroncken cat tehuys) (Ms. 1196, fol. 47r). The rain could also be something of a blessing. In the afternoon of 16 May 1630, three houses in the street adjoining the embassy’s residences were set ablaze. Only a well-timed shower prevented the fire from spreading even further.

‘A great lover of art and all antiquities’

Not content to merely spend his time in London, Booth also toured the countryside and visited many of the grand houses scattered across the country. Few of these were as grand or made such an impact on him as Arundel House, which he describes as being of such magnificence that he deemed it more worthy of visiting than all others. It was the home of Thomas Howard, 21st Earl of Arundel, who made a name for himself as England’s first great patron and collector of the arts. After his death in 1646, his grand collection of ancient Roman and Greek statues and inscriptions was bequeathed to Oxford University, who housed it in the Ashmolean Museum, the first museum of antiquities in England.

Booth’s observations of the House, which he visited in early March 1629, and the presentation of its art are of great value, as the original 16th-century building no longer exists. Although he provides few details of the building itself, Booth takes care to enumerate all the types of items in Arundel’s collection. According to him, the house contained innumerable objects of worth, including tombstones and statues, hailing from all corners of the world, spanning the entirety of the Roman, Greek, and Egyptian territories, as well as beyond. Curiously, he felt the need to point out that Arundel’s love for the finer things in life was so unlike the nature of the English. A quip at the expense of the English, or an innocent remark?

Collecting souvenirs

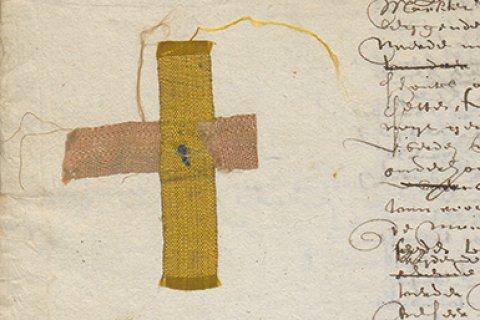

During his tour around Cornwall, Booth and his companions came across a small village where they were hoping to rest a while before continuing their journey. According to Booth, this was in ‘Foy’ (Fowey), although that sleepy hamlet lies only about eight miles further along the route (Merens, p. 154). Whatever the exact locale, Booth writes that it was customary for any first-time visitors to make a donation in support of the local hospital. In return they received a ribbon, red and yellow, which was pinned crosswise on their sleeves. Booth’s ribbon can still be found in his journal. It seems the idea of receiving a token in return for contributing to charity is not just a modern one.

Journey back home and married life

Booth did not remain in London long enough to see the negotiations come to an end. He was called upon to become the new town secretary of Wijk bij Duurstede near Utrecht. Leaving England in June 1630, he eventually arrived in Utrecht in July. Back home, he married Johanna van Hagenouwen of Wijk bij Duurstede in 1631. Booth was not to enjoy his married life for long. He died on 19 September 1636, leaving behind no children. An official cause of death was not recorded, but it is known that he already suffered from kidney stones at a young age, and it is possible this condition eventually proved fatal. His papers and affairs were passed on to his older brother, who – as librarian – ensured they were well preserved.

Personal or public?

It is unknown whether Booth meant for his journals to be made public. The journal he wrote during his embassy to Sweden in 1627 and 1628 was eventually published in Amsterdam by Michiel Colyn in 1632. The apparent five year gap between its writing and publication, it is not inconceivable that he may also have been working on preparing his English journals at the time of his death. In their current state they were likely not considered fit to be sent in for publication. His report of the Swedish and Polish embassy was entirely focused on the affairs of the diplomatic party, and contained little information on Booth’s own activities. They certainly did not include descriptions of leisurely trips around the countryside. Perhaps it is a stroke of fortune that his English journals were never published. The originals could have been lost in the process, and with them the content that brims with personality and make them such an interesting read today.

Aftermath of negotiations

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the delegation that Booth had accompanied did not succeed in solving the issues that had arisen between England and the United Provinces as a result of the Amboyna Massacre. The problems would persist for several more years, and although some sort of resolution was reached in 1634, the incident would remain a point of contention for many years to come. The two countries waged war three times over the course of the 17th century, and each time the Amboyna incident was cited as an example of Dutch brutality, if not a direct cause for hostilities (although actual reasons for going to war differed each time). Even over a hundred years later, during the Anglo-Dutch war of 1781-1784, Amboyna featured prominently in English pamphlets. Thankfully, the matter has been laid to rest since then.

Author

Nick Becker, July 2015