Sandra van der Hel: Rethinking relationship between science and politics for sustainability

PhD Research

How can research effectively address society’s challenges? Are principles like interdisciplinarity, transdisciplinarity, co-production and solutions-orientation actually changing the way we do research for the better?

Sandra van der Hel is a research fellow and lecturer with the Copernicus Institute of Sustainable Development, Utrecht University where she researches the role of science in sustainability governance. In this interview she tells us about her recently completed PhD research, where she investigated how and with what effects new ideas about science are taken up in large international science institutions.

Your work looks at the role of scientific institutions and researchers in sustainability governance. Can you tell us about this?

Over the past decades research has come to understand a great deal about the sustainability challenges society is facing, but despite this we have been very slow to address and solve these challenges. The assumption that more knowledge about the environment and society leads to better sustainability governance doesn’t seem to hold.

So how can research effectively address society’s challenges? Scientists, funding agencies and policymakers have been grappling with this question for a while, with principles like interdisciplinarity, transdisciplinarity, co-production and solutions-orientation each at some point proposed as the new silver bullet.

So where does your research come in?

It’s not clear whether the way science is done is actually changing along with these new principles of scientific knowledge production. Do they actually result in changes to scientific institutions and practices, and if they do, how so, and with which effects?

Can you give us an example?

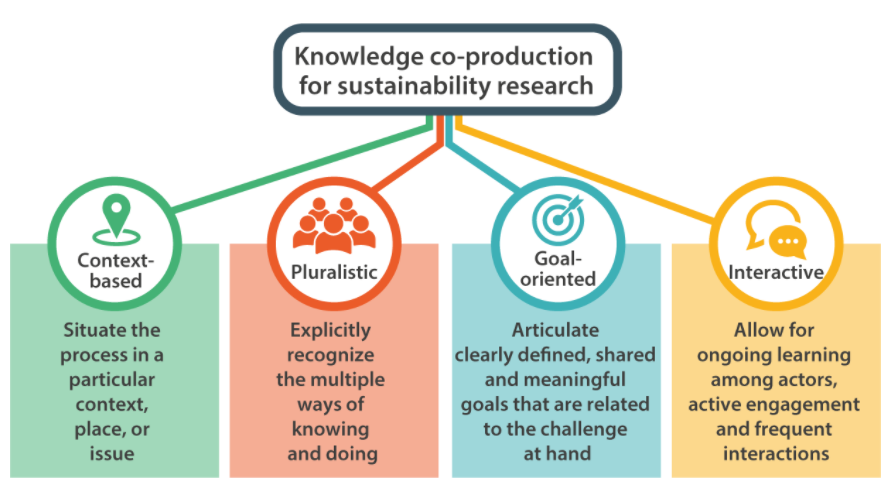

Let’s take co-production, which, broadly speaking, is the idea that researchers, practitioners and the public work together in the generation of knowledge. It’s a flexible concept that can be implemented in many different ways: which stakeholders do you work with, what is their role in the project, and what do you hope to achieve by involving them? These differences can mean you end up producing very different kinds of knowledge.

You looked at what co-production meant in the context of international research platform Future Earth. What did you find?

I wanted to know how this flexible idea of knowledge co-production would affect the rules, norms and practices of knowledge production in Future Earth. Initially, Future Earth was very vocal in putting forward co-production as a new way of doing science. Co-production was presented as a way to bring new perspectives into science. But over time its focus turned to amplifying the voice of science and communicating science to societal decision-makers. The idea of opening up knowledge institutions and creating knowledge together with a wide range of stakeholders was moved to the background.

This meant that Future Earth has tended to work with actors that already have a strong hold in science and governance for sustainability, rather than supporting new voices and challenging current ways of thinking.

This makes it political, right?

Yes. My results show that science institutions for sustainability are inherently political. They are affected by and affect important political conversations on what sustainable societies look like and how sustainability transformation can be achieved.

It’s not clear whether the way science is done is actually changing along with these new principles of scientific knowledge production. Do they result in changes to scientific institutions and practices, and if they do, how so, and with which effects?

Saying that science is political is a bit tricky, because it is easily dismissed as a critique on scientific practice. I don’t mean researchers being fraudulent with their data or policymakers changing scientific facts. The politics of science is way broader and deeper than this. It means that science can not be seen as an independent or neutral input in political decision-making. Instead, science and scientific institutions are themselves part of political processes.

And how do researchers see themselves in all this?

I was curious to see how sustainability researchers deal with the normative and political dimensions of their own day to day research. To study this, I conducted a survey which was completed by almost 300 researchers. There was really a wide range of responses, but almost all respondents agreed that they wanted their work to contribute to societal change towards sustainability.

This then raised the question how researchers engaged with the politics of what societal change for sustainability looks like, who benefits and who loses, and who gets to shape it. Many researchers do think about the political nature of science and the issues that surround this, but others explicitly split science and politics, holding on to the idea that science needs to be relevant but neutral.

But this doesn’t work when it comes to sustainability, right?

Exactly, because sustainability is always about normative questions about what sustainable futures look like and how they can be achieved. Personally, I think separating science and politics is not only impossible but also undesirable, and that we need much more explicit engagement with questions of politics in science for sustainability.

What’s next for you?

I’ve started a post-doc on the potential of creative practices for sustainability transformations as part of the H2020 CreaTures project. I really like this because I can work with researchers, artists and designers that are passionate to make a difference in society. It is also again a domain where questions of governance and politics are important but often hidden, and I would like to bring those to the fore.

Further reading

- van der Hel, S. (2020). New Science Institutions for Global Sustainability. PhD Thesis

- Esguerra, A. & van der Hel, S. (2021). Participatory Designs and Epistemic Authority in Knowledge Platforms for Sustainability. Global Environmental Politics, 21 (1). Pre-published version

- van der Hel, S. (2019). Research programmes in global change and sustainability research: what does coordination achieve? Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 39, 135–146.

- van der Hel, S. (2018). Science for change: A survey on the normative and political dimensions of global sustainability research. Global Environmental Change, 52, 248–258.

- van der Hel, S., & Biermann, F. (2017). The authority of science in sustainability governance: A structured comparison of six science institutions engaged with the Sustainable Development Goals. Environmental Science and Policy, 77, 211–220

- van der Hel, S. (2016). New science for global sustainability? The institutionalisation of knowledge co-production in Future Earth. Environmental Science and Policy, 61, 165–175

- Norström, A.V., Cvitanovic, C., Löf, M.F. et al. 2020. Principles for knowledge co-production in sustainability research. Nature Sustainability 3, 182–190. https://doi-org.proxy.library.uu.nl/10.1038/s41893-019-0448-2